Varoom 39: Clive Hicks-Jenkins and Hansel and Gretel

The Nostalgia issue of Varoom features Clive Hicks-Jenkins’ edgy retellings of classic fairy tale Hansel and Gretel. Taking in the original story’s horrific neglect, abuse and murder, Clive has adapted it into a picturebook, toy theatre and original stage production. Alongside Clive’s startling manifestations of the familiar fiction, in an online exclusive Olivia Ahmad talks to him about his practise and his feelings on the role of illustrator.

Hansel & Gretel: a nightmare in eight scenes

Olivia Ahmad; Do you consider yourself an illustrator? And if you do, is there a particular moment that you first felt that way?

If you don’t necessarily, where does something like the Hansel & Gretel works fit in to your creative practice as a whole?

Clive Hicks-Jenkins: Whenever people ask what I do, I describe myself as an artist. If pushed to define what kind of an artist, I explain that my practice veers toward ‘narrative’ exploration. Narrative, I suppose, might be interpreted as telling a story, and so perhaps that makes me an artist with an interest in storytelling which occasionally spills over into illustrating books. But when I began working as an artist, my interest in narrative manifested exclusively through the medium of paintings and drawings, made for exhibition and sold in galleries. My focus was not books, but the easel. I wanted to tell the story of myself. I was enormously influenced by Picasso, who drew on the deep well of personal history to create art that went far beyond the particular and into the universal. I didn’t want to make things up. I wanted to start with what I knew best, which was me.

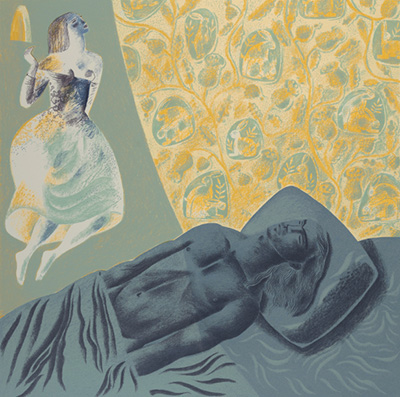

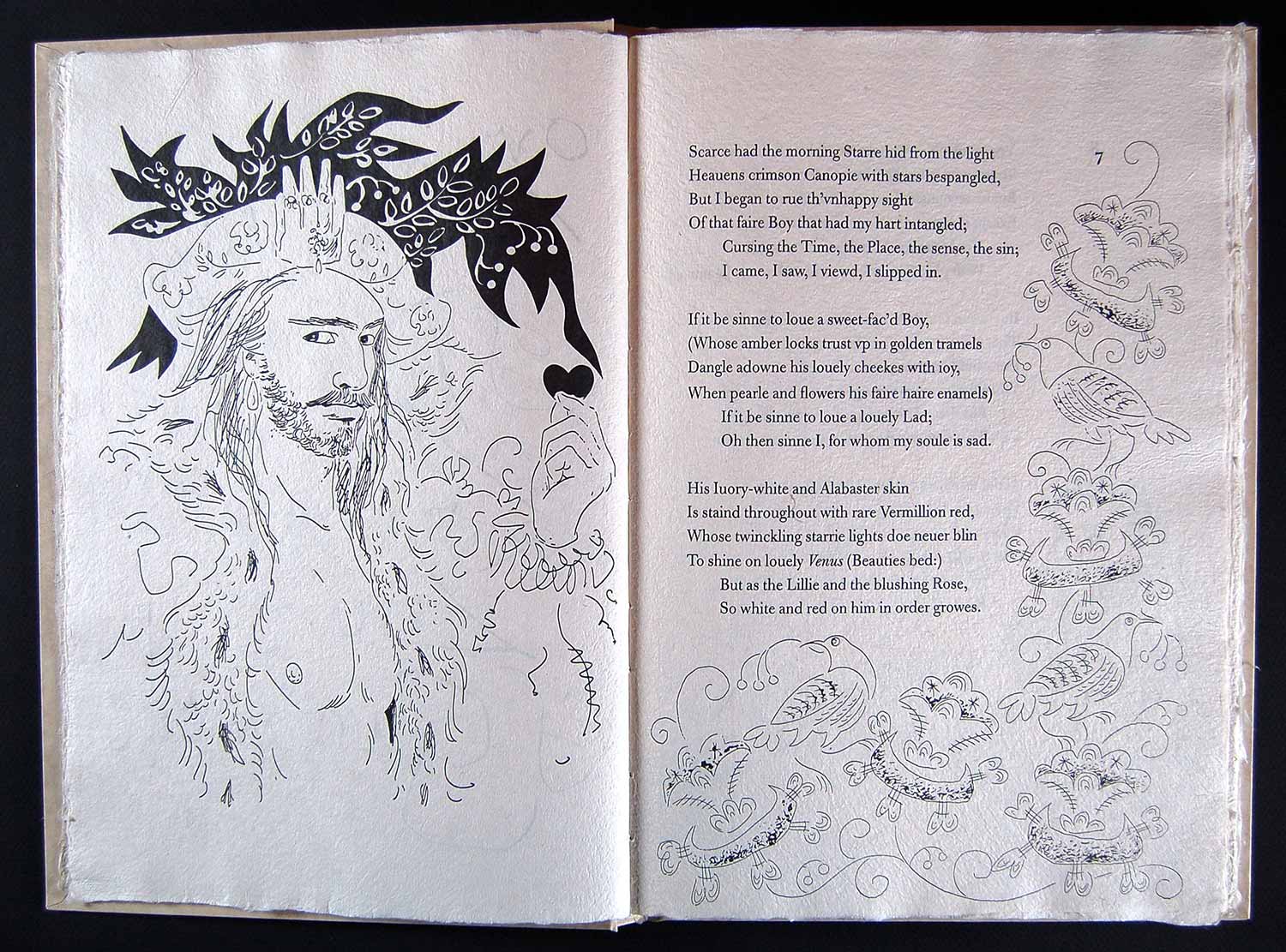

Richard Barnfield’s narrative poem, The Affectionate Shepherd

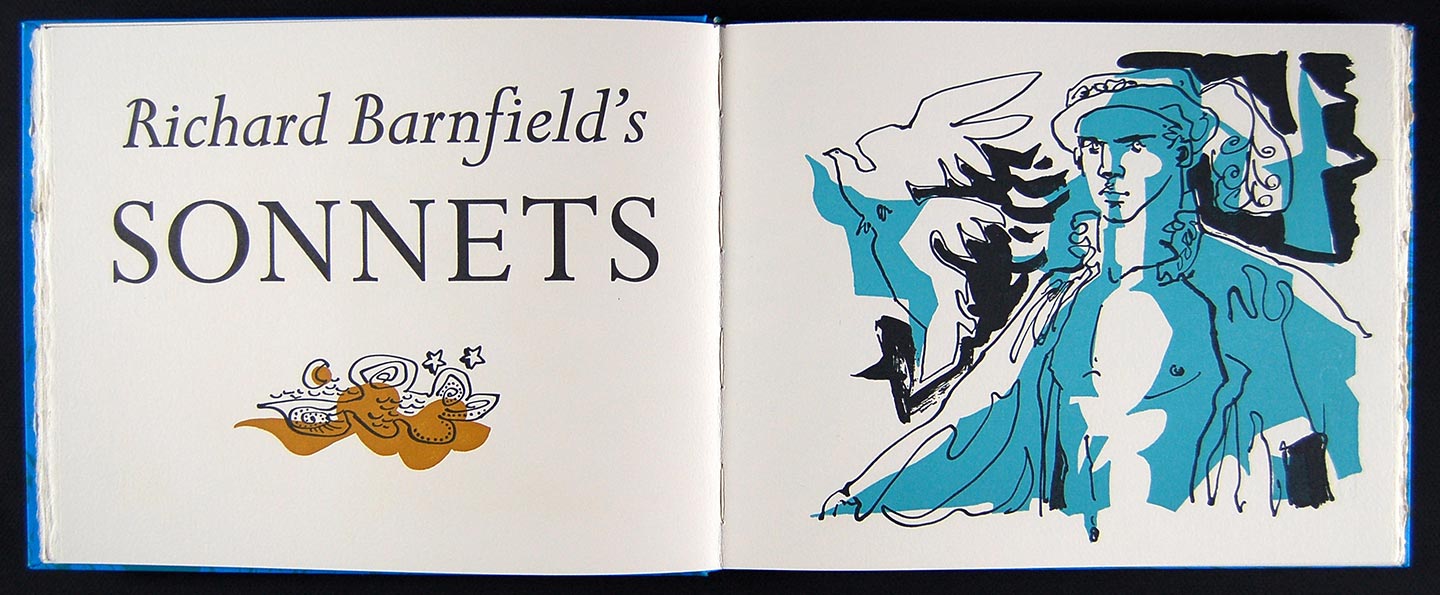

My first opportunities to ‘illustrate’ presented themselves early, in several collaborations with Old Stile Press. Based in the Wye Valley not far from Tintern Abbey, the ethos at OSP has been to specifically work with artists who haven’t experience of decorating books, encouraging them to explore beyond easel practice and into the world of ‘fine press’. Printer/publisher Nicolas McDowall was first drawn to my paintings, and then turned me loose on Richard Barnfield’s narrative poem, The Affectionate Shepherd, originally published in 1594. Together with Frances McDowall, who made the paper, in 1998 the three of us produced the first illustrated edition of The Affectionate Shepherd, followed in 2001 by an illustrated edition of the complete Barnfield Sonnets.

Above and below, Barnfield Sonnets

The Mare’s Tale (Old Stile Press, 2001) is a sequence of narrative poems by Catriona Urquhart, who produced them in response to two events: the death of my father, who was her great friend, and the series of drawings I subsequently made as an act of mourning and exploration. The poems were written as the text for an exhibition of my drawings, but when Nicolas determined to publish the poems, I produced new drawings specifically for the edition.

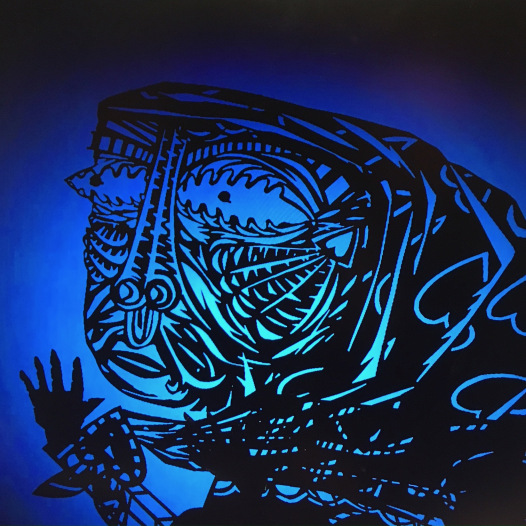

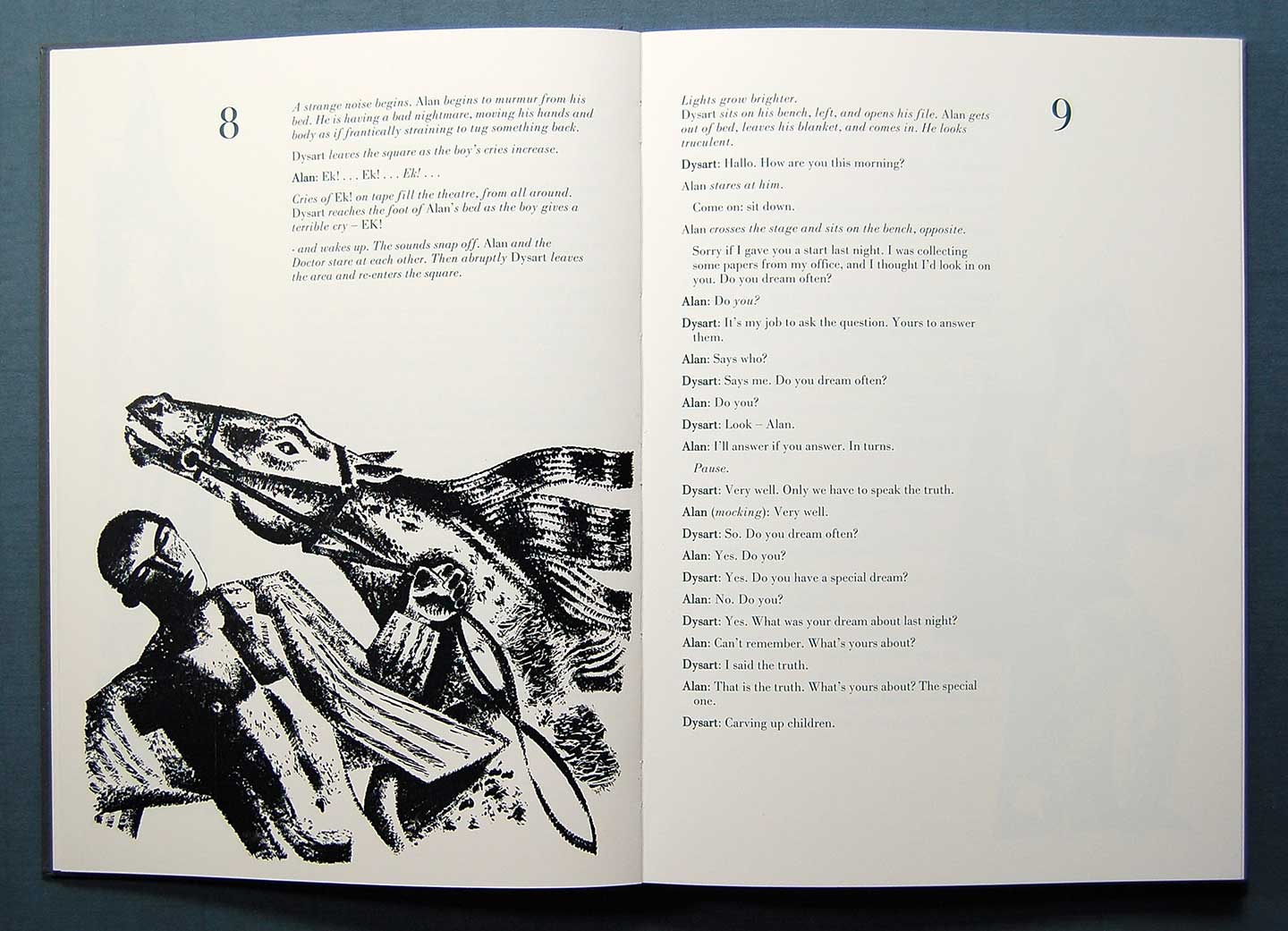

My final major project with OSP was making an illustrated edition of Peter Shaffer’s play Equus (Old Stile Press, 2009), which in turn led directly to my making the cover for the play in its current Penguin Classics livery. I’ve also produced cover illustrations for two volumes of Old Stile Press Bibliography, and I’m due to make the cover for the third, and last, this year.

Equus, Old Stile Press, 2009

While I greatly enjoyed my work with OSP, I found the long process of producing private press books to be quite frustrating, and moreover I was increasingly anxious about spending so much time on beautifully produced though small-ish editions beyond the pockets of most. So when opportunities arose for me to work with publishers producing books at an affordable price and with larger distribution, I was attracted to the idea. Nevertheless I remained cautious about presenting myself as an illustrator, not least because I wasn’t actively seeking work in the field.

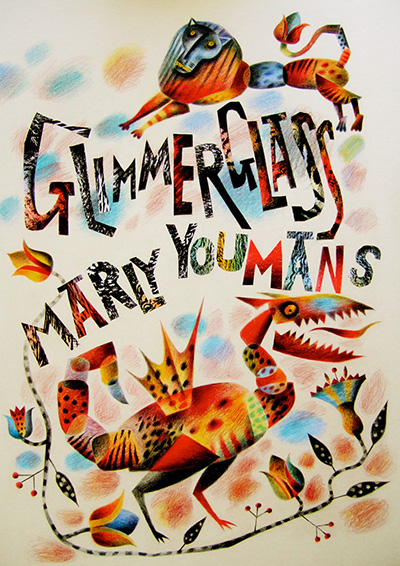

If I balk at labelling myself, it’s for no reason other than not wanting to mislead anyone. To start with I’m not trained as an illustrator. The illustration work I’ve done has developed out of my practice as an artist, and particularly from my friendships with poets, which then somehow evolve into collaborations. When approached to work on a book, it’s nearly always by the author. For my friend, American novelist and poet Marly Youmans, I’ve made covers and vignettes for a half dozen books from several publishers, and in every case she’s just taken me along as a part of her deal. For Marly I’ve produced covers and illustrations for: Val/Orson, PS Publishing, 2009, The Foliate Head, Stanza, 2012, Thaliad, Phoenicia Publishing, 2012, Glimmerglass, Mercer University Press, 2014 (below), Maze of Blood, Mercer University Press, 2015, and forthcoming this year, The Book of the Red King from Phoenicia.

Glimmerglass, Mercer University Press, 2014

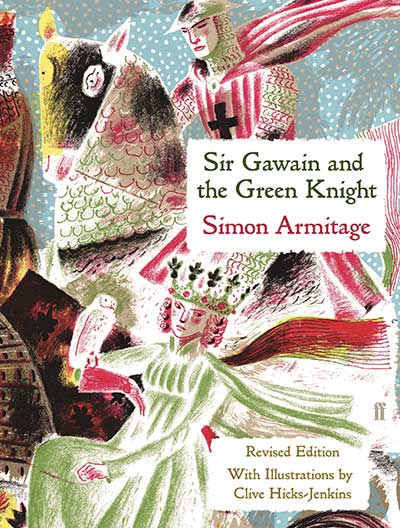

The same thing happened with Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Simon Armitage walked into my life, took me by the hand and led me to Faber & Faber. Recently I’ve been approached by an editor to produce commissioned images for English Heritage Magazine, but that’s a first. I’m not represented by an illustration agency, and so I kind of blunder my way through whenever approached, always prefaced by the admission that I don’t really know what I’m doing.

Sir Gawain and the Green Knight by Simon Armitage, Faber & Faber

Sir Gawain, published in October 2018, certainly seems to have placed me more in the arena of illustration, though even that project originated as a series of fourteen editioned art prints made in collaboration with Penfold Press, which were then co-opted by Faber as illustrations for the book. When talking with publishers, I always explain where I’m coming from, and confess to being old school, with no understanding or aptitude for digital. In terms of up-to-the-minute technology, I can’t compete with young illustrators emerging from art schools. In fact when small changes were required of two of the Gawain images for the book, I turned to my friend, artist Mark Brown, for help, and he digitally made the adjustments for me. Magic!

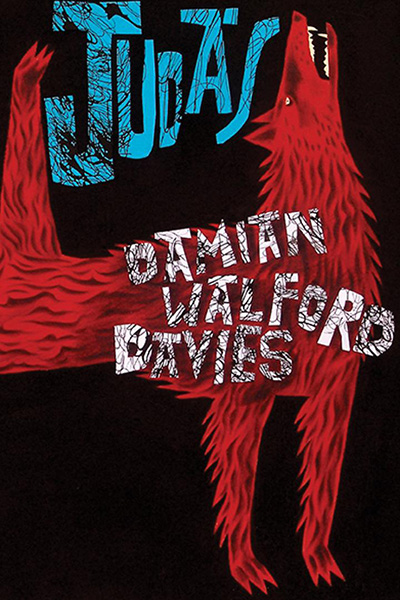

It’s a fact that I’ve never liked being pigeonholed, and if I’m candid, I’ve never felt entirely comfortable in any single creative field. I like the boundaries to be fluid. That said, I’ve recently started to add ‘illustrator’ to my CVs, though I’m anxious that may make people expect something I can’t deliver. It’s a conundrum. And of course it can, and occasionally does go wrong. I’d made two covers for the poet Damian Walford Davies, both published by the small Welsh publisher Seren. But last year, having at Damian’s request made a cover for the third in his trilogy of novella-length narrative poems, it was unexpectedly rejected by the publisher, who instead decided to go with an ‘archival’ photograph, explaining he believed that painted covers, unless made in a photorealistic style, were ‘old-fashioned’. (If that’s the case then an awful lot of illustrators are going to be in deep shit!) It was a grim experience.

Are feelings of nostalgia, which is the theme of this issue of Varoom, or attempts to evoke aspects of the past an important part of your wider work?

Not nostalgia. I’m no such fool as to think that yesterday was better. (I was there, and it wasn’t!) My explorations are all about objects being repositories of histories. They’re like radio dials, and if you twiddle them you ‘hear’ the past. That past can be anything, from sweet to despairing. It’s the focus that’s all important, and what that focus opens in the mind and heart. I make art for myself, which is why I sometimes find myself at loggerheads with those who try to tell me that what people think about what I produce is all important. It’s not. It’s only what I think that counts. If anyone else gets something out of what I make, then that’s a great by-product. What I don’t want to do is presuppose or second guess. I never shout for people to stop and look. I just present what I’ve made, and leave it for them to linger, or to move past.

To see the Dark Tales article on the Hansel & Gretel projects purchase Varoom 39

Read our review of the Hansel & Gretel book

Clive Hicks-Jenkins site

Back to News Page