The Varoom Report: Obsession V24

OBSESSION

THE ILLUSTRATION REPORT Winter 2014

The visual equivalent of Earworms? Eyeworms. Nice. Still, how else to describe the images in Varoom’s Obsession issue – an issue about Obsessive practice, Obsessed with Neon, Obsessed with Ladybird, Obsessed with Outsider Artists who are Obsessed with One Thing or another – sometimes One Thing and another. Writer Linda Scott observes that East Ham Outsider Artist Madge Gill would paint, knit and sew while in a delirious trance, whilst in possession of her spirit guide Myrninterest. Don’t try this at home kids. While Barcelona illustrator Mr Mourao says in our feature, We’re Lost In Pictures, “The main goal is to draw as much detail as possible so that the viewer gets sucked in and gets lost in the drawing.”

Varoom editor John O’Reilly discovers the roots of Obsession in his introductory Report to this issue.

1.1 Fixation and Movement

The Pope caused our current obsession with Obsession. It’s a long story, Obsession always is. Not knowing when to stop. That’s Obsession. Actually, it’s not caring about stopping. Or caring too much to stop. Or the pleasure of being carried along by the thought, by the pen, the pencil, the scissors, by its movement. That’s the weird thing about Obsession, it’s about being fixated, but it’s also giving your self up to movement, to being moved, psychologically and physically, that comes with the creative flow of the Obsession. Obsessed. Obsessing. What was I saying? Oh yes, the Pope…

1.2 Storming The Citadel

In Obsession: A History, Lennard J. Davis, Professor of English at the University of Illinois at Chicago, plots the evolution of Obsession. Its original Latin meaning was rooted in the notion of battle, in besieging a city. Obsessio and possessio were the two parts of taking over a city. ‘Obsessing’ a city meant to surround it, while ‘Possessing’ it meant you had stormed the city.

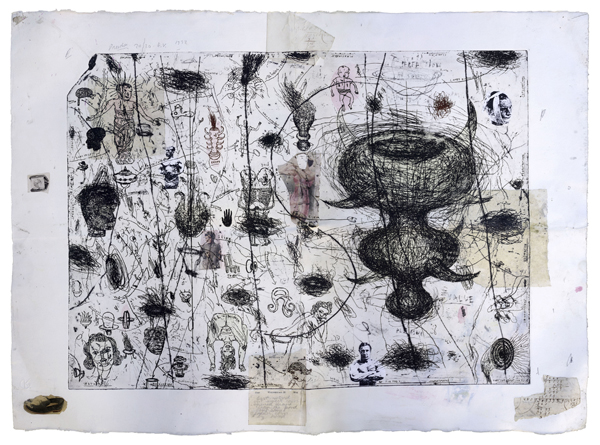

Henrik Drescher, Dolphin print

1.3 The Devil Is In The Detail

Then up until the 18th Century explains Davis, Obsesssion was believed to be a supernatural force, an instrument of the devil. Similar to the dynamics of besieging a city, being possessed meant your soul had fallen to the devil, while if you suffered from obsession, you were aware of the devil’s presence, force, power, that you were in danger of losing control.

1.4 Rituals

The Act of Parliament in 1736 removed laws against “conjurations, inchantments and witchcraft,” and according to Davis the notion of possession was banned by Protestants because Catholicism’s rituals around exorcism gave it “the inside track”. Removing laws was a means of removing ‘Popery’. Though demonic possession was still a generally popular notion in the 18th Century, what slowly began to take its place was the medicalised, pathologised notion of Obsession we have today – Obsession as a kind of illness.

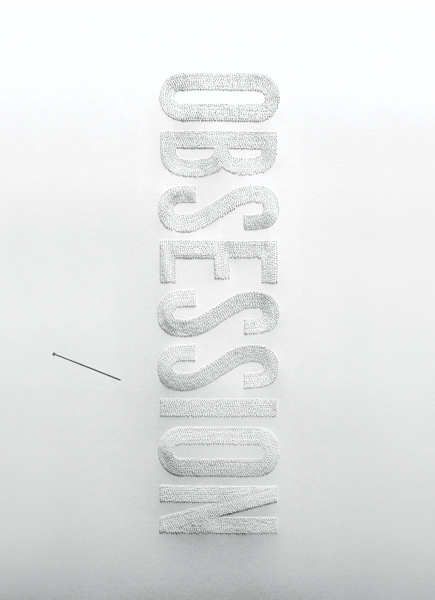

2.1 Skin

Yet image-makers and designers have a much richer relationship to Obsession. Take, for example, the cover of Obsession: A History, designed by Isaac Tobin with lettering by Chicago illustrator Lauren Naseef created, through creative obsession via pinpricks. It’s a great cover because it shows how we are inhabited by Obsession, the pinpricks, don’t break the surface, the skin of the page. Obsession pushes at boundaries – the pictorial, the graphic, the emotional, the methodological boundaries.

Cover of Obsession: A History, by Lennard J. Davis, 2008. Illustration, Lauren Nassef. Design, Isaac Tobin

2.2 On The Border

Illustrator and RCA lecturer Catherine Anyango explores the borders of domesticity and the abject, the forlorn, in her immensely detailed Tile imagery we feature in We’re Lost In Pictures. “I am very interested in domesticity and abjection as a subject matter,” says Anyango. “Hygiene and disorder are part of the realm of the abject and I am fascinated by that border between clean and unclean, order and disorder. This comes across in the tile images because there is a tension between the very geometric lines and the lack of ability to control the settling of the paint within those lines.”

2.3 “Can’t Get You Out Of My Head”

Obsession itself crosses the borders between the Domestic and the Exotic. Obsessive habits, cleaning, making lists, are incredibly mundane but deliver a buzz of pleasure, even if this pleasure is the pleasure of the addict. The pleasure of repeating, of repetition, like the chorus or refrain of a song that you can’t get out of your head. In the same We’re Lost In Pictures feature, artist Ed Loftus explains that when making his hyper-realistic graphite drawings he usually has “a backlog of images in my head and sometimes it’s a couple of years work.”

Ed Loftus, Untitled (Living room), 2010

2.4 Physical Therapy

Loftus’ image-making is incredibly time-consuming – another feature of Obsession. Obsession consumes time, eats it up, it has a taste for time. Yet the creative individual is paradoxically someone whose creative Obsession gives them the freedom to waste time. Ed Loftus battles with what psychologists call Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and in an interview with The New York Times he says what’s compelling about drawing is “the single-minded goal and the physical contact. You’re mentally immersed in it, and it’s a repetitive practice so it’s therapeutic.”

3.1 Homesick

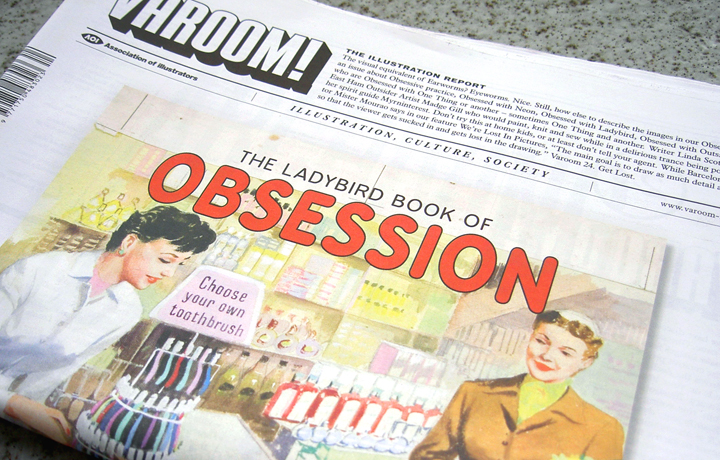

An obsession with the past is called Nostalgia, though Nostalgia has its own etymological and clinical history – ‘homesickness’ diagnosed by Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688. In this issue of Varoom we explore the power images from the past can have over us, Lawrence Zeegen reflects on growing up in Basingstoke with his world extended and fashioned by illustration from the world of Ladybird Books.

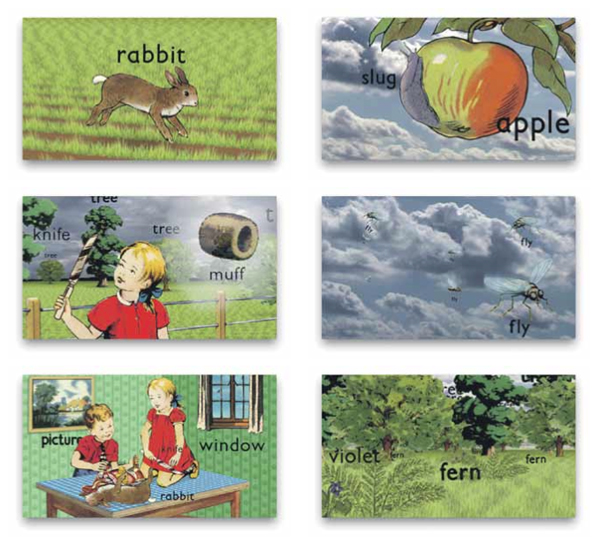

3.2 Ladybirding

“I was six years old when the 1960s ended,” writes Zeegen, “how much I really knew about the fast-moving and ever-changing world is debatable, but what I did know is that I had a thirst for learning about my own small world. And Ladybird seemed to really understand my world; understand just what I wanted to know and understand how to present it to my eager and enquiring mind.”

Shopping With Mother, by M. E. Gagg. Illustrated by J. H. Wingfield, 1958

3.3 Pleasure of Looking

History, Geography, Science. And Shopping With Mother, a sensible suburban version of what French Jesuit philosopher Michel De Certeau would call The Practice of Everyday Life. Buying daffodils, a hammer, cake, socks, a toothbrush. Rosey-cheeked, bright-eyed and school-blazered security, all lovingly visualized by illustrator Harry Wingfield in pictures with narrative detail training you in the pleasure of looking.

3.4 Empire of Tidy

I loved Ladybird books too. I loved their Adventures Through History, and even as a young Irish boy growing up in Leeds, its secure, confident, Anglo-centrism was oddly comforting in its black-and-white vision of the world. But it was mostly the pictures, the narrative authority of the vertical imagery, the size of the book, the way they stacked neatly on your shelf introducing you to the experience of tidy satisfaction that belongs to the collector.

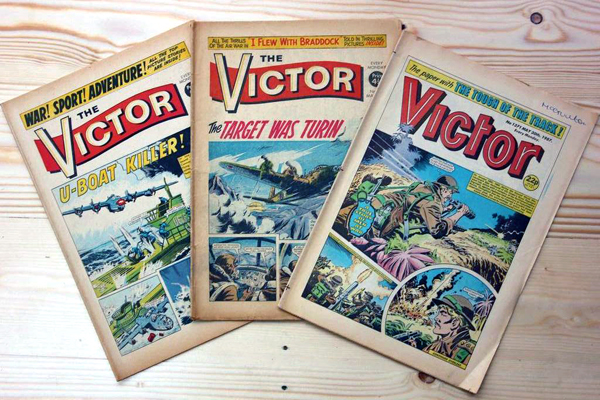

4.1 Warchild

In his feature, The Birth of Obsession, Ian Horton was drawn into The Victor comic as a young boy, its stories of WW2 acting as a bridge between him and his parent’s generation who had lived through the war. It was a gateway to a richly different experience of narrative. “It was distinguished from other boys’ adventure comics,” writes Horton, “by the quality of the illustrations themselves rather than the stories told… the term Narrative Drawing could also be applied to much of the work in The Victor, with its loose pen and brush work and an instant dynamic rendering of the key elements of the story.”

4.2 Vertigo

While children of the 1960s and 1970s such like Zeegen and Horton were discovering the imaginative thrill of illustration via Ladybird and comics, illustration already occupied an iconic, curious, and central role in the representation of Obsession in the world of grown-ups. Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane topped Sight and Sound’s critics Poll of Top 50 films for over 50 years. Until the last poll in 2012 when it lost top spot to Alfred Hitchock’s Vertigo. Despite the title, the film wasn’t about fear of heights, but the story of a man’s Obsession with a ‘copy’, featuring an illustrator as a character and revealing the visual as a psychological driver of Obsession.

4.3 Systematic Passion

Vertigo is the only movie for which Saul Bass designed both the poster and the title sequence, the poster’s now classic swirls signaling the ‘vortex’ of obsession – obsession visualized as a black hole into which we are spun, or truthfully which we spin into ourselves. Obsession, whether is a method we find to create something, whether that’s a way of working, of making images, or a passion – you could say that obsession is simply a way in which we make a passion or a love, systematic, ritualized, rigorous. Like the rigorous pattern of swirls in Saul Bass’ Vertigo poster.

4.4 The Illustrator vs Kim Novak

Think of Vertigo as a movie about two women image-makers, and one man’s obsessive interpretation – let’s call him a critic. Ex-detective ‘Scottie’ Ferguson’s (James Stewart) is obsessed with actress Kim Novak who plays waitress Judy Barton imitating then mysterious Madeleine Elster. His ex-fiance the independent-minded commercial illustrator Midge Wood (Barbara Bel Geddes) is a smart, worldly woman, but can’t compete with the otherworldliness of actress Kim Novak for James Stewart’s affections.

4.5 Copy of a Copy

The supposed madness of Madeleine is represented in an image – a painting of Carlotta Valdes, a suicidal aristocrat who ‘possesses’ the soul of Madeleine. If Madeleine/Barton is obsessed with this image, so is the James Stewart character. The spiral in Carlotta Valdes’ pinned-hair, is echoed by the spiral in the pinned-hair of Madeleine/Judy, is echoed in the spiral/swirl in Saul Bass’ classic poster. Are you now lost in this detail about hair, have you lost the thread, forgotten how you got here? Welcome to obsession, and its love of fabricating narrative out of the microscopic and the granular.

5.1 Get Lost

Like Ed Loftus’ graphite drawings, often mistaken for photo-collages. Or the crushingly detailed architectural drawings of Barcelona-based Mr Mourao whose strategy, you could call it an obsessive strategy, “is to draw as much detail possible so that the viewer gets sucked in and gets lost in the drawing.” His immensely detailed structures generate a dizzying, vertigo-effect, as the tight vertical, horizontal, diagonal lines suck up space and absorb the eye into ever-receding corners and nooks.

5.2 Obsession Implosion

Two kinds of creative process in Obsesssion. Sometimes the Obsessive image-making process means stripping things back. Mr Mourao chooses to work “with a black pen and paper because it doesn’t leave much space for questions/excuses. I can only draw and don’t have to waste time choosing between an infinite set of options.” This is when Obsession is creative implosion.

5.3 Obsession Explosion

Sometimes the Obsessive image-making process means amplifying materials, or letting materials amplify themselves. “I have a house and studio packed with objects and printed ephemera”, says Peter Quinnell who hoards materials for his assemblages, collages and Box Art. “I don’t like to file it too specifically, as it is particularly pleasing when objects come into unexpected juxtaposition.” Quinnell’s objects that are filed away – the Bart Simpson model, the toy dinosaur, the bag of cheese puffs – are images already arranging themselves into narratives into “unexpected juxtapositions”. For the collage artist, materials amplify and multiply narratives. Obsession as creative explosion.

6.1 Obsessive Rhythms

And if there is one common obsession among illustrators and designers it’s music. “For many creative practitioners, particularly those in design and illustration”, writes One Dot Zero’s Shane RJ Walter in a feature on the work of the late animator Run Wrake, “music transcends merely listening and underscoring studio life. Music is a tool used to inspire, toil to, and infuse work.” Because Obsession is often repetitive, it has rhythms.

Run Wrake, Rabbit, 2005

6.2 Loop. Repeat.

Walter also draws our attention to a music promo by Cyriak Harris, whose uses archive footage to create a series of mesmeric, repetitive, looped images that ‘grow’ into a machine. The original found imagery celebrates the world of the consumer in 1960s America, and this sparked the idea to “create the whole video as a vast repeating mechanism that the camera slowly scrolls across,” says Harris. “It is a machine whose purpose is to create itself, much like the western capitalist society glorified in the original footage.”

6.3 Unofficial Change

Obsession it is a kind of unorthodox, ‘unofficial’ behaviour we construct to facilitate change, to make things happen that we wouldn’t ordinarily be able to do. Even dull, classic psych theories of Obsession see its symptoms as a way of both avoiding change but also clue to showing how change can happen. The mind constructs its own language of strange symptoms to avoid and facilitate change.

6.4 The Threshhold

Imagine Obsession as a threshold from one place to another. When we create the circumstances for this kind obsessive creativity, our single-minded passion enables to ignore others’ indifference. One of the many fascinating ideas discussed by Linda Scott in her feature on Outsider Art, is how difference, creativity, the new, is addressed by educators faced by young students with an innovative visual aesthetic. “From time to time,” writes Scott, “a student shows up with an intensely personal and sometimes obsessive visual language that one might categorize as way beyond the broad range of approaches often explored and executed within the illustration field – one might go so far as describing the work as that of an Outsider. Similar to the work of the Outsider Artist, the imagery is raw and often has an obsessive quality, peppered with repetitious marks and motifs.”

Carolyn Gowdy, Wake Up Call, 2007

6.5 Style Obsessed

As commercial image-makers, illustrators are often caught in a very different kind of obsession, that of the commissioner who wants the same image, the same style, “just like the funny one you made for the marmalade packaging.” Earning a living sometimes means getting trapped in someone else’s obsession. The trick to developing your career, keeping it fresh and provocatively relevant, is to manufacture, multiple obsessions – one obsession at a time.

6.6 Time Obsessives

In our always-online culture obsession has been displaced by its close relative ‘compulsion’ – checking in on twitter, feeding our social networks, uploading images, looking for feedback, pop-up shops, pop-up-shows, pop-up pop-ups. Zoe Lazarus, from agency Lowe and Partners recently wrote in Ad Age that, “a side effect of all this cultural acceleration is that our brains are becoming hard-wired to crave instant gratification. Unlimited access to information and desire for external validation is altering behavior….We want more new. And we want it now.” The stimulus-response mechanisms of social-tech helps us to think we want more ‘new’. But the reality is, the really ‘new’, the truly different takes time. As our feature Lost In Picture shows, it takes time to get lost and discover the new. It’s why we need more Obsession, more image-makers Obsessing over image-making.

7.1 Can’t Get You Out Of My Head

Damn. Kylie.

More on Varoom 24 here, and to purchase Varoom 24 go here

Back to News Page