Varoom 39: Tracing History

History can seem abstract, until people you know, or think you know, become part of it. Serena Katt learnt only so much about her Polish-born grandfather Günter’s life growing up in Nazi Germany from conversations and his brief writings.

Since his death, however, Katt tells Paul Gravett in this extract from Varoom 39, she has used drawing to delve deeper into his conflicted past. Her tender yet incisive graphic memoir ‘Sunday’s Child’ considers what we choose to remember and to forget.

How did ‘Sunday’s Child’ begin?

While my Opa Günter was alive, I knew about his achievements in later life, but very little about his youth. He had a habit of painting a golden picture of himself and repeating the same success stories of his adult life over and over.

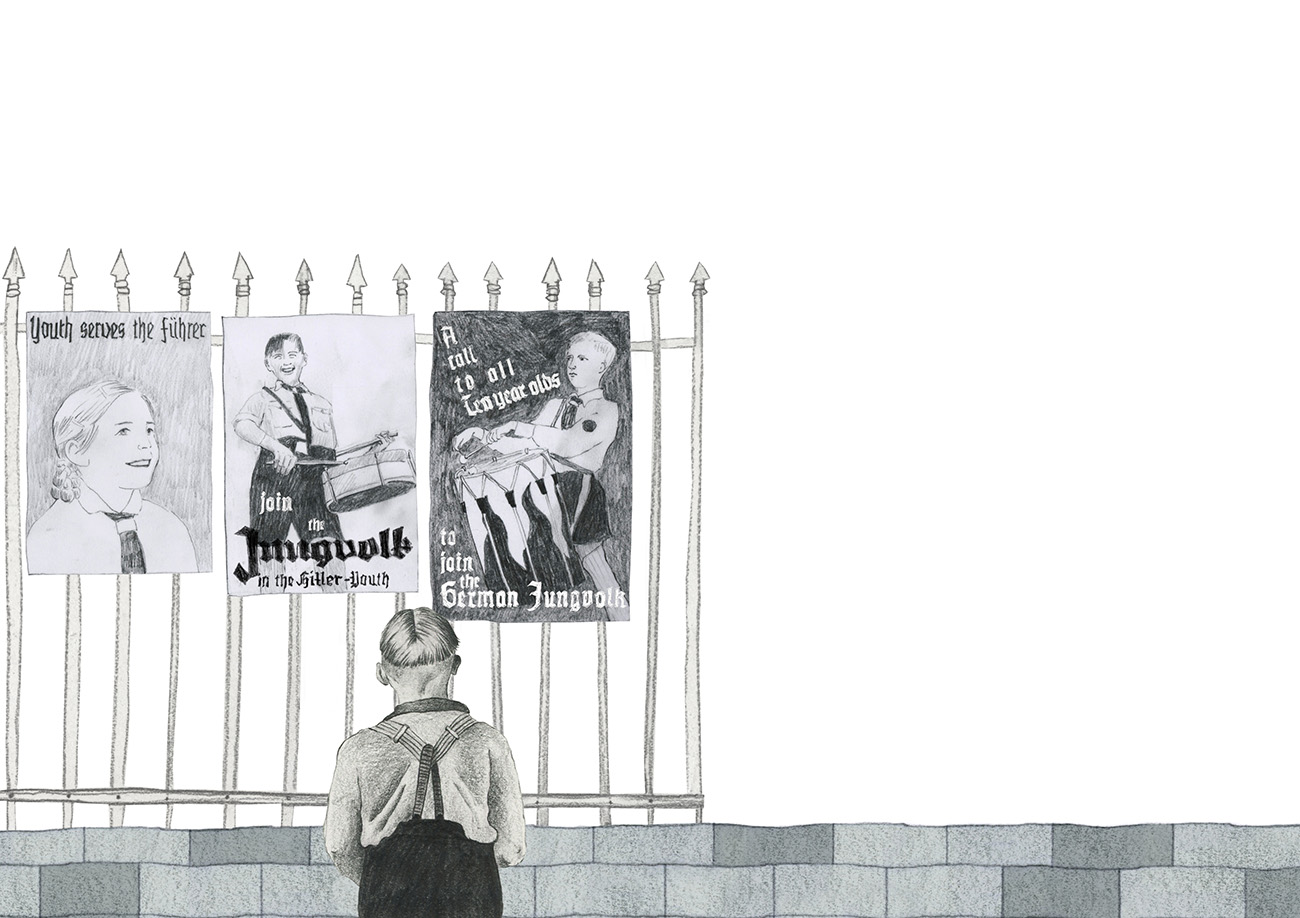

Günter grew up in Germany during the 1930s – like most German boys, he joined the Hitler Youth. Later he attended various military training programmes, spending the entirety of his boyhood in Nazi education facilities. After he died, a closer inspection of his short written recollections helped me learn more, and inspired me to dig behind his facade.

How did your grandfather share the memories of his youth with you?

A few years before he died, he wrote down what he called a ‘Lebenslauf’ (or C.V.) for me. That was mainly in response to my interest in our family history. He wrote in some detail about his family, and then he ran through his own life, chronologically, with small anecdotes here and there, but it was brief – just five typed A4 pages.

In beginning the research for the book, I interviewed Günter’s sister to see how her memories of those times correlated with what he had written down, and if she could fill in some blanks. She was open to talking, but she knew even less than my Grandfather had documented about his experiences in Nazi educational facilities. She said everything was very ‘hush-hush’ and no one really knew where anyone was being sent or what they were doing.

Your working process consists of redrawing an image multiple times, each time responding to and improving on the previous one. What are you seeking through this process of distancing and distilling?

Each image in the book has been drawn at least three times, and always in response to the previous drawing. Drawing and redrawing a person allows me to get ‘closer’ to them – to empathise with them – but in doing so, I am aware that I am filtering them through my own experiences, and so I add a layer of distortion to their story. This is on top of all the filters and biases that have already been applied to my sources – the accounts I hear and read and the archive images I use. I am working with a paradox – I am looking for ‘truth’, whilst knowing full well that there isn’t one, universal truth, particularly when talking about history or memory. The act of drawing helps me to contemplate these mechanisms of bias and distortion.

‘Sunday’s Child’ is completely rendered in pencil. Does the graphite suggest something fragile, tentative, unfinished, erasable – like a memory – and unlike say the definiteness of pen and ink?

I had never thought about it like that, but I think that’s an interesting way of reading it. Pencil allows me to work with an intensity that I haven’t found for myself in other mediums. Also, I can achieve a wide tonal range that is reflective of the black and white photographs I am working with, that I couldn’t achieve with pen, for example.

Nora Krug (author of graphic novel ‘Heimat’) has said that post-war generations of German children have been taught about the horrors of the Second World War in school. But privately, the truth about what relatives actually did during the War must often be left unspoken. Is facing up to these ’skeletons in the closet’ the next essential stage of dealing with the echoes of the war and the trauma it causes still today?

I think so, though I also believe in many cases it’s never going to be fully possible, at least not for the people who were directly involved. There are so many layers of trauma, guilt and shame that need unravelling. In the case of my Grandfather, what I see is that trauma and guilt were very mixed up, one eclipsing the other. I don’t believe he would ever have been able, even he had been willing, to really face up to his ‘skeletons’.

As a relative and an illustrator, I felt my role was to perceive his experiences and emotions, and portray them as best I could, in all their discomfort and obscurity. It was about putting myself in his shoes in order to gain a greater understanding of how he experienced and dealt with his situation. Illustration was ideal for this exploration, as it exists to communicate, to create a dialogue.

Read the full article in Varooom 39

Back to News Page