Varoom 38: War In The Neighborhood

An activist since the 1980s, Seth Tobocman has also been a chronicler of injustices in comic form revealing the internal struggles and sometimes problematic relationships within groups challenging conventions and power imbalances.

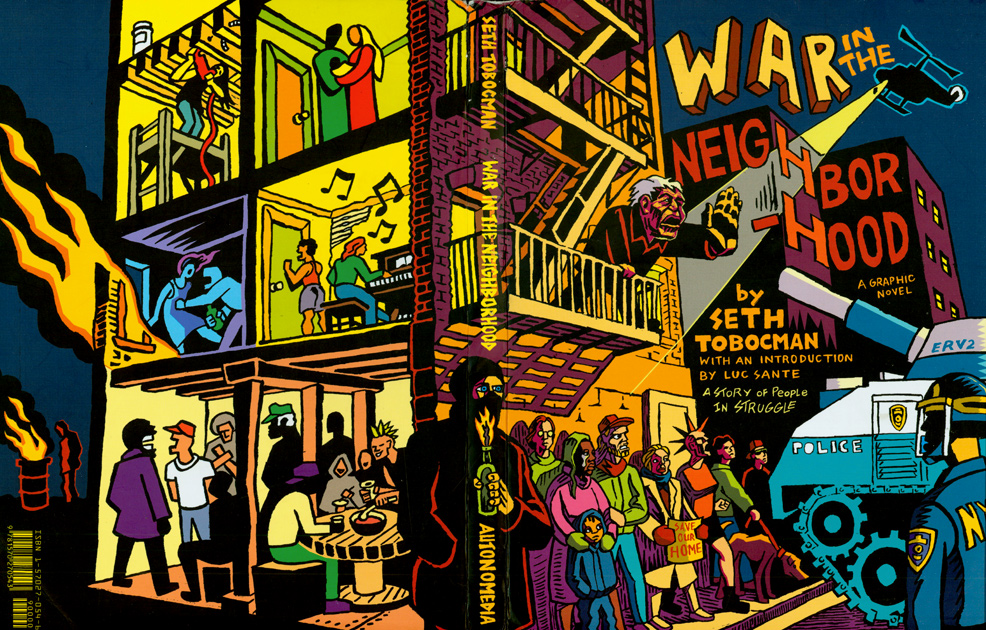

The Activisim issue of Varoom features Seth’s recent work, Albany Without Polar Bears from an ongoing project If If There Is A Future, This Is Your History Part, a series of comic strips covering the fight against fossil fuel infrastructure. For this online Varoom exclusive Seth discusses his 1999 graphic novel War In The Neighborhood, reissued in 2016 by Ad Astra Comix.

Varoom: What are the main elements that fire the drive to cover these stories, from NY East side squatting to the control exerted by major oil companies across the globe?

Seth: I generally become involved with a story through work with activists. I usually wait for people to invite me to participate.

In the 1980s people began squatting buildings in my neighborhood. I was asked to do posters for their demonstrations. Since it was, at first, a very small movement, I was soon asked to help organize the protests, then invited to join a squatters collective myself. Soon I was up to my eyeballs in this situation. I got arrested about 20 times. Eventually I needed to step back from it. At that point I wrote and drew my graphic novel, War In The Neighborhood.

More recently I was asked to make banners for a day of actions protesting the oil trains that go through Albany New York. I went up there a month in advance to meet neighborhood people and research the situation. And that experience provided the basis for a comic strip.

How important is it to source first-hand accounts of the situations you are covering? And to include relevant facts and figures?

I feel I do my best work when I am very involved in the situation. When I get to meet people and interview them. I use a combination of reference materials. I do sketches from life, take pictures, record interviews, but I will also ask others to let me see photographs they have taken and use what I can find on the internet or read in books to fill in any holes in my knowledge.

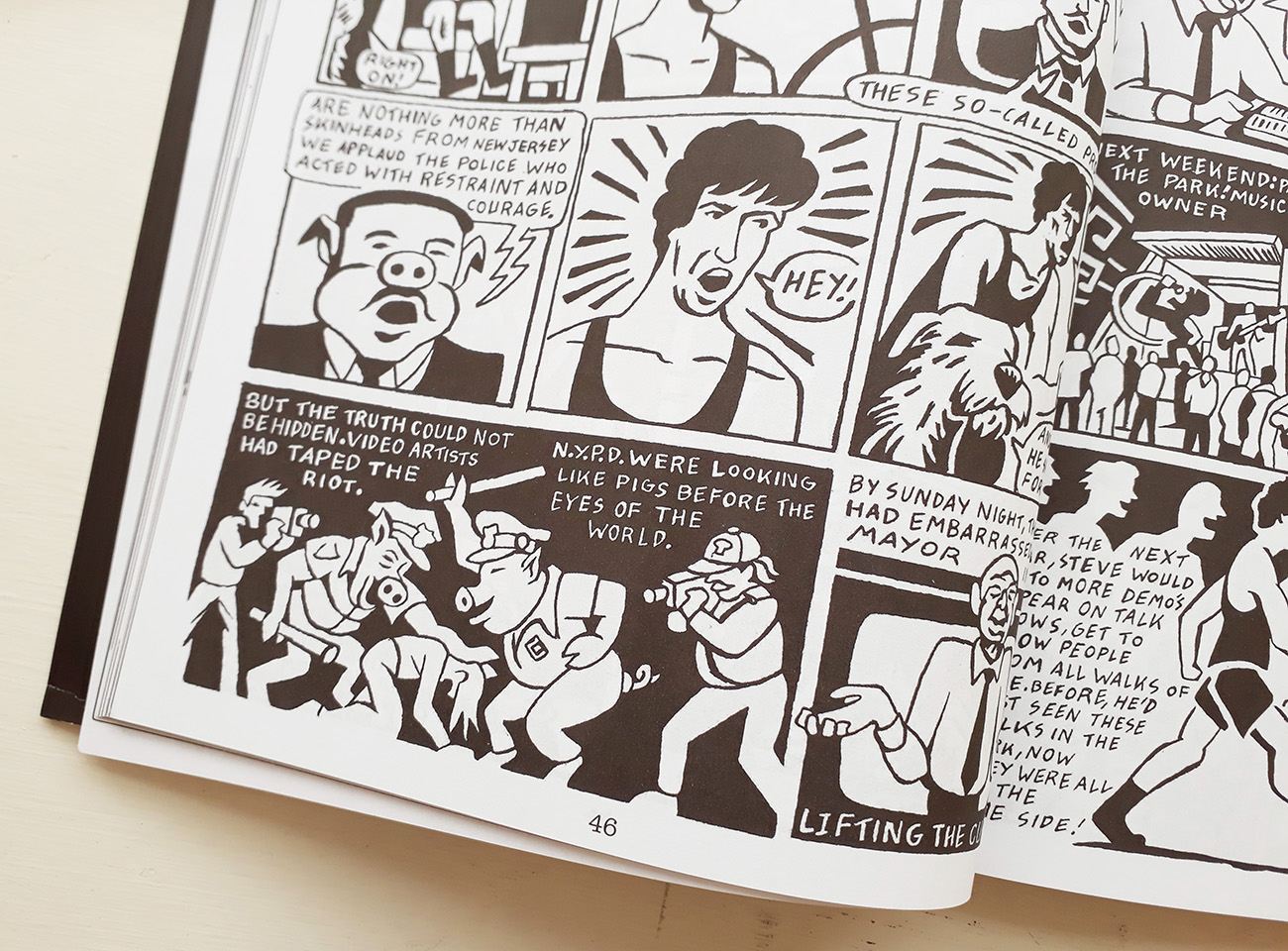

Within the comics you successfully combine realistic depictions with more stylised visualisations of broader themes such as the power of the state or oppressive systems. How do approach these elements visually?

Real life gives you a lot of great ideas. Very often you will see things, discover things, that are so extreme that people think you made them up. Like the huge oil tanks being right next to the playground in Albany. Or some of the police violence in War In The Neighborhood. But then I try to honor that content with the whole language of comic book form. Exaggerated anatomy and perspective, monsters, stuff jumping off the page. I grew up on Jack Kirby comics and I love that stuff. Very often, you can comment on a scene, without changing any of the basic information, just by the way you apply your materials.

You place a significance on addressing what has changed and acknowledge what was done right, but also what was done wrong (covered in the ‘War in the Neighborhood’ afterword). Is it useful to be able to revise your views on past work?

I think I have an obligation to the next generation of activists to record things in an honest and useful way. When I first got involved in politics in the 1980s, I could find plenty of books on Marxism or Anarchism or about movements in other countries or about the 1960s portrayed in a very romantic, or subjective, and not very useful way. It was hard to find anything that would tell me how to organize a demo, how to deal with the police, how to handle disagreements in a group. So after my squatting experience I tried to remedy that for the next bunch of people coming up. I’m now reprinting some of that work twenty years later, and some of my views have changed, so I have to re-examine it and make sure everything I said was right.

We asked Seth about the collection of stories which make up War In The Neighborhood:

Brief: War In The Neighborhood

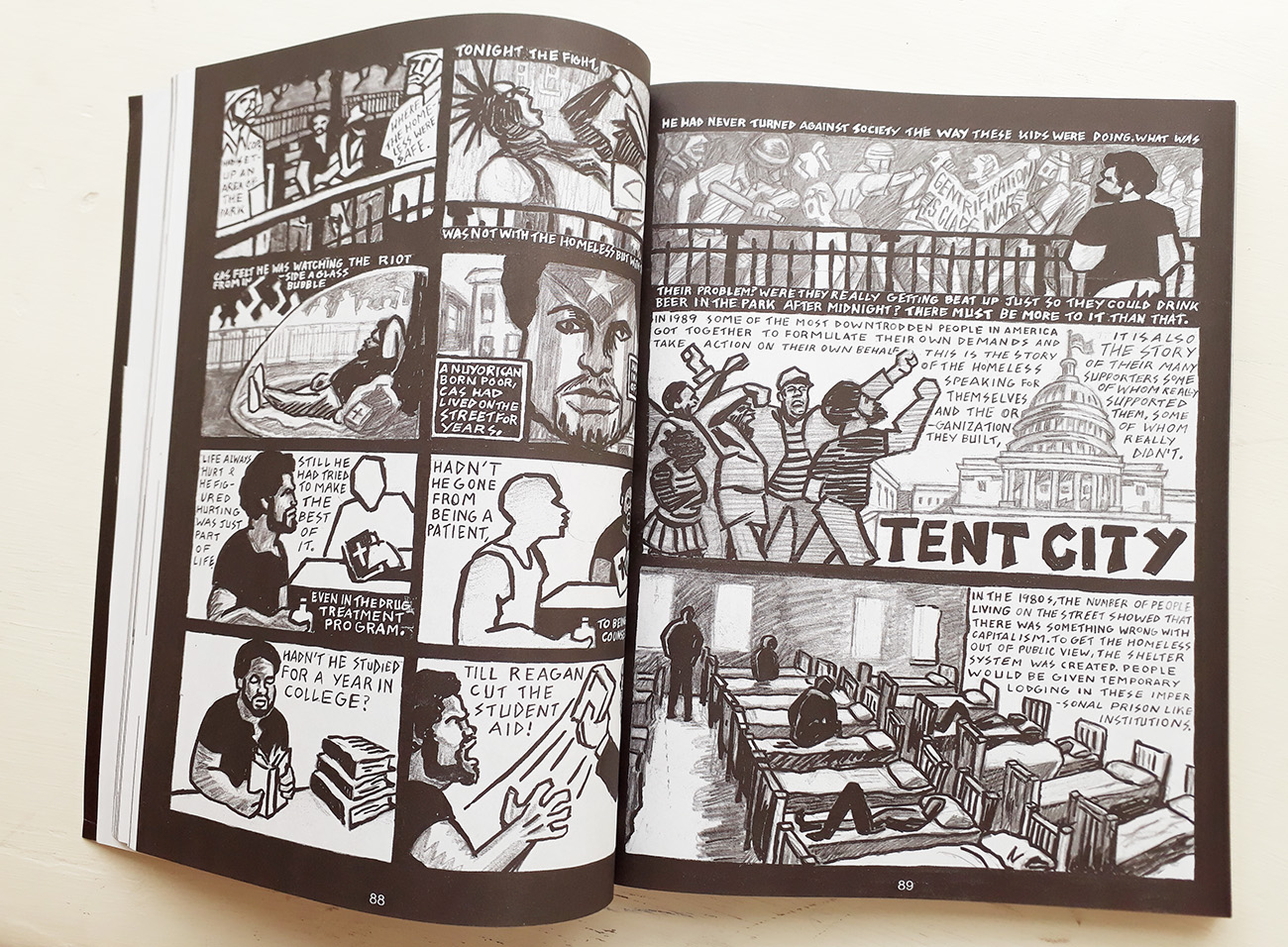

Idea: Portrays the radical scene on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in the late 1980s and early 1990s through a series of interlocking stories loosely based on real events I had participated in and people I knew.

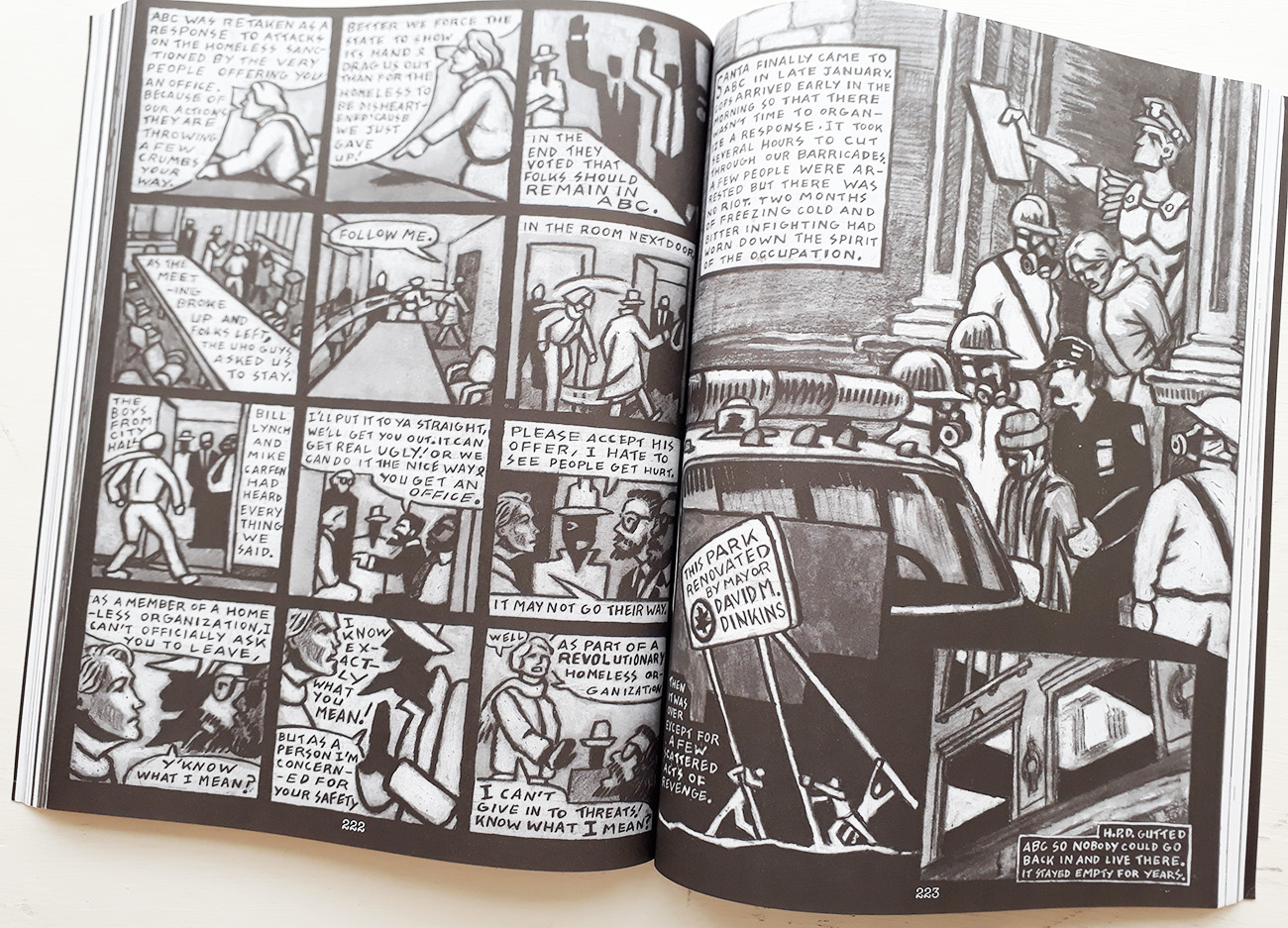

Materials: Most of it was done in black ink on paper in a very traditional black and white comics style. But at a certain point I found I had to work in graphite and gray wash. I felt I needed grays to catch the feeling of the city at night. I also found that when a lot of characters are people of color it is good to be able to show a variety of skin tones.

Research: 6 years life experience, then interviews, life drawings, photo references from many photographers who had been at the same demos I went to.

Process: Interviews, then scripts, then storyboards, then drawing. It took years.

Resistances: It’s hard writing about people you know, knowing that they may not like it. It was hard working with something that was so emotional for me. Recording some of the best moments of my life but also some huge disappointments.

Insight: Political movements are about more than ideas. You may start out with an idea, but that idea has to be acted on by real human beings, Individuals, who are very complex.

Distractions: When I was trying to finish this book, my friend Micheal Shenker (the Maestro, in the book) kept trying to get me to do more actions, more civil disobedience, and I usually said yes, after arguing for an hour or so.

Numbers: Over 10 years, over 300 pages

Activism: There is a cycle. People can’t stand the way society forces them to live, but they don’t know what to do about it. Then a way of resisting is discovered and everyone jumps in. For a while the state doesn’t know what to do. Then they find a way to stop us, they bust some heads but also make a few concessions. We win a few things but the energy is exhausted, most people go back to their lives, and people who want to do it over again find that they are stopped at every turn. But people still hate the way they are forced to live and eventually find a new way to resist and the cycle starts again.

More of Seth’s work can be seen in the World War 3 comic, an anthology of political comics, which he founded with Peter Kuper.

“In 1979 Peter Kuper and I started World War 3 illustrated with two ridiculous ideas. The first was that comic books could be a medium for serious political discussion. The second was that the American “New Right” was a crypto fascist movement that would eventually have disastrous consequences that a future generation would have to correct. I think history has proven us right on both counts.”

Back to News Page