Varoom 32 – Under Water

Industry Insights: Interview with reportage illustrator Leah Fusco

Article from print issue Varoom 32

By Derek Brazell

Atmosphere plays a significant part in how we perceive and remember a place. The lay of the land is all around us: the rise and fall of the hills, roads, streams and ditches cutting through solid or marshy land. Leah Fusco’s work has consistently used an atmospheric monochrome ambiance to investigate landscape, influenced and shaped by humans over time, but with their actual presence lightly touched upon. The weight of the British weather, grey skies, rain and fogs, forms a depth to her images and bring together the contemporary place with an interpretation of its past.

Owling, 2010

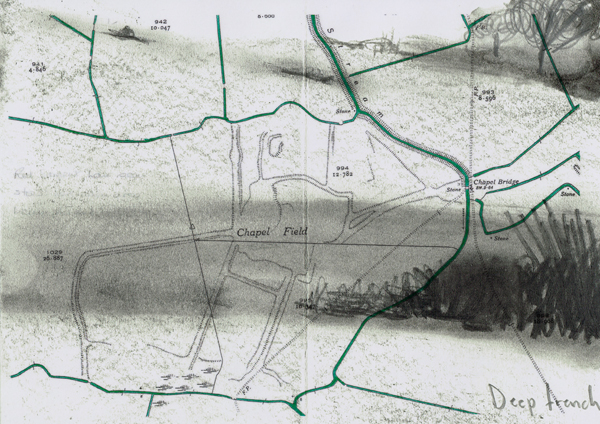

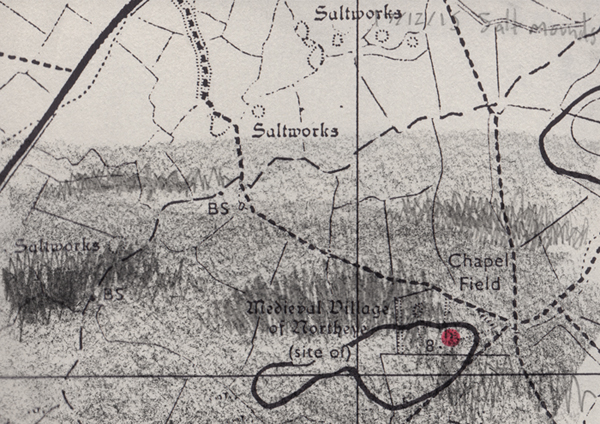

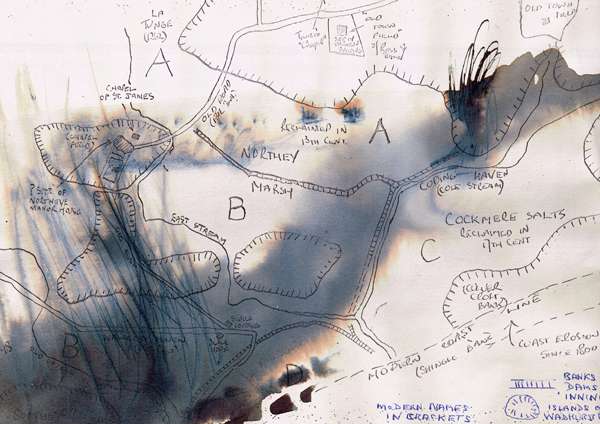

Following her Owling project, tracing the historical smuggling of wool and sheep out of Romney Marsh in Kent to France, Fusco started a PhD, and through her research discovered Northeye, an area of saltmarsh in East Sussex which was once a medieval village. Using illustration to reinterpret archive material of the area she has created a moving image piece revealing the changes to Northeye over the centuries. The transient nature of the marsh area is investigated as Fusco layers drawings from her field trips to the area over maps detailing the site layout of the deserted village, surrounding fields and marshlands. Stills from the film shown here combine the observational with the apparently practical, as drawn trees and grasses obscure the clarity of the maps, much like the marsh waters claimed Northeye.

These images reflecting the hidden village, show how a “visual narrative can reveal and illuminate previously unseen or hidden stories for new audiences,” says Fusco, and express her vision of exploring alternative timeframes through the application of illustration.

Mapping Northeye, still, 2015

Leah Fusco – Illustrator

BRIEF: Mapping Northeye is a short moving image piece that tracks the physical reshaping of a medieval island. The work forms part of my ongoing PhD research on lost histories in landscapes for Kingston University, supported by LDoC AHRC funding.

IDEA: I became interested in marshland areas whilst doing my MA in Communication Art and Design at the Royal College of Art. I started to explore the area of Romney Marsh in Kent, uncovering histories and practices that were specific to the area and produced a series of paintings that explored Owling – a historic form of smuggling wool and sheep out of England to France. The images trace smuggling routes across the marshes and contain historic and contemporary details within the landscape. They allude to the endurance of smuggling in Romney Marsh, from wool to drugs, because of the unique physical qualities of the marshes – its isolation, sparse population and proximity to the coast. From a distance, the images are read as anonymous landscape paintings but close up reveal stories of this hidden industry.

Owling, 2010

After completing my MA I continued to document lost histories in rural areas, observing the cultural and socio-economic shaping of communities by physical environment. Carrying out research through libraries, museums, local history talks and field trips, I was eventually led to Northeye, a DMV (deserted medieval village) located on a salt marsh in East Sussex, which I’m using as a case study for my PhD. Strangely, the site is only a few miles away from where I grew up but I had no idea of its existence until years of research led me to it. Talking to other local residents, it became clear that knowledge of Northeye was obscure and this in itself was suggestive of the site as ‘hidden’ or ‘lost’.

MATERIALS: Charcoal, graphite, ink, paper, archive material.

RESEARCH: The film stills observe the visual remnants of Northeye and explore challenges in documenting physically shifting landscapes. Marshlands are areas of transience; geographic and man-made details are revealed and concealed repeatedly through dynamic water levels. I’m interested in how water based processes make history (in)visible and how illustration practice can be employed to explore and capture alternative timeframes and temporality.

Mapping Northeye, still, 2015

PROCESS: “There are definite advantages to staying in the same spot for long periods of time. Partly you accrue information in a very slow natural way and partly you can see how long the place breathes and changes.” – Iain Sinclair, Psychogeography

Repetition, revisiting and experiencing place over time has shaped my approach to documenting rural areas and (re)drawing the site of Northeye has helped me to measure long and short term changes in the landscape. A collection of visual diaries have emerged as a result of multiple fieldwork trips, which will be an ongoing research method looking at time and materiality in drawing based documentation.

Alongside this work, I’ve been carrying out archival research at Bexhill Museum and focusing on their collection of around 25 maps of Northeye.

The resulting moving image piece tracks the shifting landscape of Northeye over 10 centuries from the effects of tsunamis and salt mines to the Black Death and smuggling. Drawing together key pieces of primary (my location drawings) and secondary research (archive material), the work examines the role of illustration as a narrative device for inhabiting territory between past and present readings of the site.

Mapping Northeye, still, 2015

RESISTANCES: In times of high rainfall, parts of the old foundations of the village are filled with water and made visible. This only happens for a short while, so my field trips are very dependent on catching the site in specific weather conditions.

INSIGHT: Through the process of my wider research around landscape and memory, I’m developing my knowledge and understanding of other humanities disciplines, such as anthropology and ethnography and how these help frame my illustration practice.

DISTRACTIONS: You uncover an enormous amount of information through the process of working towards a PhD. It’s by far the most in depth and investigative project I’ve undertaken and can very easily take detours. It’s a balance of remaining open to new approaches to your subject but also being able to edit your work and have confidence in the bigger picture of what you’re trying to achieve.

NUMBERS: 3 (minutes, length of film) 1000 (years, history mapped).

THE NEW: The work suggests the function of illustration in reinterpreting archive materials and how visual narrative can reveal and illuminate previously unseen or hidden stories for new audiences.

Varoom 32 is available from our online shop

Back to News Page