Varoom 30 – Play: The Art Game

Full article: Any commute will reveal there are as many tapping away on games as there are readers, mailers or folk who actually use their phones as phones. The trade body for the UK games industry, Ukie, estimates that by 2017 the global games market is expected to grow to $102.9 billion. More surprising is that UK made Grand Theft Auto V, is “the most successful worldwide entertainment product of all time including movies (grossing $1bn worldwide in just three days)”. For illustrators, the video games industry potentially offers a high score.

Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art is a timely book by John Sharp who gets leverage on the field of games and gaming by accessing it through the theme of art games and practices. Sharp is Associate Professor of Games and Learning at Parsons, a member of the game design collective Local No. 12.

Works of Game is a fruit-gobbling Pac-Man of a journey through culturally significant games, from Japanese Fluxus artist Takako Saito’s Fluxchess series in the 1960s and 1970s, to Robert Rauschenberg and Jim McGee’s 1966 performance Open Score anchored by a tennis match between painter Frank Stella and Mimi Kanarek a tennis pro, to key contemporary figures such as Cory Arcangel.

Siochan Leat by Brenda Romero, 2009

Structured by chapters such as Game art, Artgames, Artists’ Games, and Games as a Medium, some of the most compelling analyses emerge from Sharp’s own affective experience playing games by such as Jonathan Blow who creates in games including Braid (2003) “a space within which ideas can be explored.” Or Brenda Romero’s “Mechanic is the Message” series which includes Síochán Leat which gives the players the experience of being Irish in the invasion by Cromwell – turning against each other to survive. And the extraordinary Train where players discover their complicity in sending Jews to Auschwitz. In the following Q&A Sharp discusses communities of practice, what illustrators might learn from games, and picks some current favourites.

Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art is a timely book by John Sharp who gets leverage on the field of games and gaming by accessing it through the theme of art games and practices. Sharp is Associate Professor of Games and Learning at Parsons, and a member of the game design collective Local No. 12.

Varoom asked Sharp to discuss communities of practice, what illustrators might learn from games, and picks some current favourites (which include Kentucky Route Zero by Cardboard Computer, Eddo Stern’s Vietnam Romance and Ed Key and David Kanaga’s Proteus).

One of John Sharp’s favourite games, Proteus, Ed Key and David Kanaga

Varoom: Could you tell us a little about your own experience growing up? What kinds of games did you play? What kinds of experiences did playing games generate?

John Sharp: I was born in the late 60s, so I more or less grew up with videogames. I can remember playing a Pong clone on a friend’s TV around 1975, and playing Space Invaders in a Pizza Hut soon after the arcade game was available in the US. All to say: I spent a lot of time playing throughout my childhood, but when I went to college, I stopped playing videogames for about a decade. This created an interesting gap in my play experiences. I missed the NES, SNES and other consoles, and the second generation of arcade games. So when I started paying attention to videogames again, a lot had changed. More importantly perhaps, my relationship to games had changed. I was no longer just a player; I was interested in the medium of games as a scholar and a designer. So adult me played differently – more analytically, with more meta-curiosity about what made games work, and what place they held in peoples’ lives.

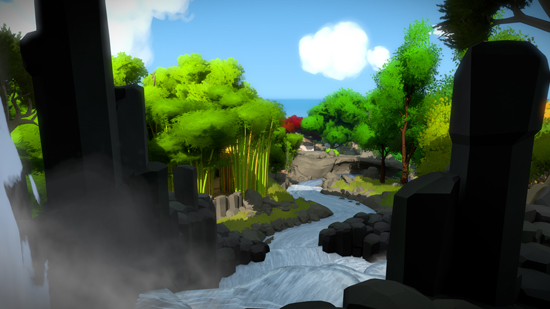

The Witness, Number None Inc. 2015. An exploration-puzzle game. the-witness.net/news/media

Varoom: Could you give a little context to the work of James Gibson and why his ‘Theory of Affordances’ is useful for designers and makers, of objects and experiences?

John Sharp: I first encountered the concept of affordances through Donald Norman’s book, Design of Everyday Things, as part of my work as an information and interaction designer. It was really eye-opening for me, as it provided a framework for considering how people form understanding of objects and their use (or experience). One of the best summations of the value of affordances comes from the web usability expert Jakob Neilsen. Paraphrasing him, people spend 99% of their time looking at things made by others. So if the things you make don’t function in similar ways as all those other things people encounter, use and understand, then you must figure out ways to make these differences readily comprehensible.

In Works of Game, I extend these ideas beyond physical objects to the ways we think about the purpose, use and experience of mediums. I believe affordances still hold, even in this more conceptual usage, as we still build up assumptions about what a medium is and isn’t good for, which influences how artists consider their medium, and what audiences expect from works in that medium.

The Witness, Number None Inc. 2015.

Varoom: You mention the idea of ‘communities of practice’ within games design, what are these different communities?

John Sharp: There are innumerable communities of practice in game design and development. There are the broad communities that come together at events like IndieCade International Festival of Independent Games which are unified through their attendance at the festival, but also in their interests in experimental and smaller-scale games. But inside of the IndieCade community, there are a number of smaller communities of practice. For example, I’m part of the broad community of practice of academic game developers and educators, but also the New York independent game development scene. Others are connected by their interest in independent games as an approach to small business management.

All to say: there are many, many communities out there, all interacting and overlapping. The important point about communities of practice is that they develop and share values about how one behaves within the community, what kinds of work the community creates, and what the community wants to encourage and discourage its members to create and consume. So if you happen to be in a community of practice that sees videogames as a business sector, sales will be an important unit of measure. But if you are in a community of practice that values experimentation, the unexpected is going to be an important shared value.

Train, Brenda Romero, 2009. Train explores complicity within systems. It also asks two questions, “Will people blindly follow the rules?” and “Will people stand by and watch?” romero.com/analog

Varoom: I was unfamiliar with the work of Brenda Romero, and the analysis really unpicks the mechanisms at work. Many illustrators struggle with synchronizing commercial work alongside personal experimental work but she has worked both fields successfully. You identify the ‘materiality of rules’ as a key aspect of her work? Could you explain this, perhaps in relation to Train and Siochain Leat?

John Sharp: By materiality of the rules, I mean their physical properties. With Train, Brenda only made a single copy of the rules. This was important to her to establish the fact that there was only one instance of Train in the world. Had she not made a point of making clear people could not copy the rules, people may have photographed the game’s rules and tried to make their own version of the game. Which largely misses the point. In the case of Train, the game is the rules, but also the materials used to give the game form. Brenda spent a good deal of time thinking about what the game should be made of, which model typewriter to acquire, and so on.

In part, this emphasis breaks with certain schools of thought around games and their design. Some think of the heart of games being their rules, and the visual and material qualities being only in service of the player’s ability to access and put into motion the game. At the same time, by treating the rules as limited supply object, she was able to get us to think about the game more seriously than we might one we could go pick up at a local game store.

Proteus, Ed Key and David Kanaga, 2013. A game of audio-visual exploration and discovery. visitproteus.com

Varoom: For illustrators, designers and creatives in general who don’t work in the games industry, what can they learn from playing games, and could you recommend a few games that illustrators might want to explore?

John Sharp: I think there is a lot to learn from gameplay. One of the things I love about games is the immediacy and directness of the experience. To experience a game, the player has to actively participate. It makes the main interfaces with which players engage a videogame – the graphical representation of the game – of the utmost importance. Being able to communicate clearly what the player is to do, what the impact of their actions are, and what their choices are for the next decision – this is a real challenge for the illustrators, animators and interface designers of videogames. I think there is a lot to admire about this aspect of game development.

The Witness, Number None Inc. 2015.

John Sharp: One of my favourite games is Kentucky Route Zero, by Cardboard Computer. It is a visually stunning adventure game made by a pair of film school graduates turned independent game developers. You can see their eye for filmmaking and visual storytelling in nearly every moment of the game.

Another favorite for its visual style is Eddo Stern’s Vietnam Romance. It is a series of small game vignettes drawing on side-scrolling game conventions. The game’s visuals are all watercolors that were carefully scanned, prepared and animated. It makes for a really unique and beautiful play experience.

The Witness, Number None Inc. 2015.

Number None Inc.’s The Witness is a soon-to-be-released game I am really excited about. The game’s art style is a wonderful mix of hyperrealism and stylization. Everything is at once realistic but also stylized in sometimes subtle and sometimes exaggerated ways.

Another visually striking videogame is Ed Key and David Kanaga’s Proteus. It is an imaginative mash up of Atari 2600-style graphics in a 3D gameworld. It is one of the most beautiful game worlds out there.

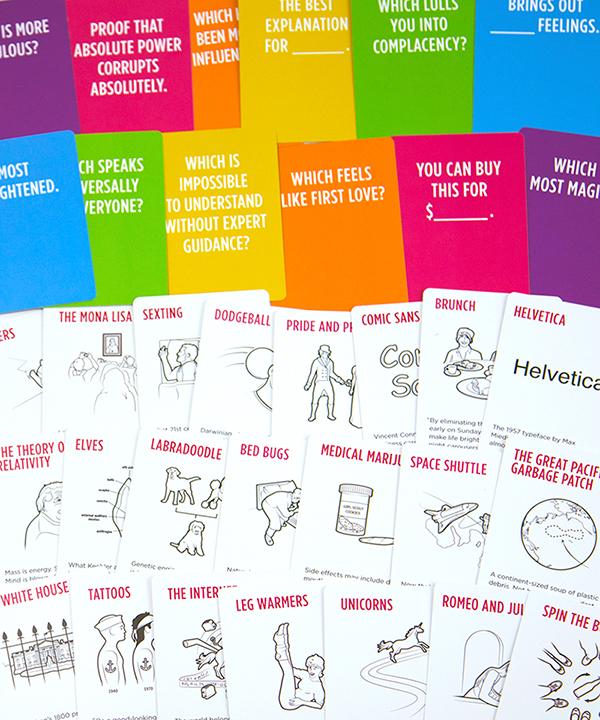

Finally, Forgive a moment of self-promotion, but I’m really pleased with how The Metagame (below) turned out – a cardgame I created with my partners in Local No. 12. We are really excited about the response we’re getting to our “picture in the dictionary” approach to illustration in the game. It turns out it is quite challenging to represent things like Disneyland, Vaseline and the collected work of the band Journey in image form.

Works of Game: On the Aesthetics of Games and Art (Playful Thinking Series), John Sharp, MIT Press, £13.95

The Metagame by Local Number 12 is available on amazon.com

Back to News Page