V33 – Girls’ World

Girls’ World: The ‘Fabulous Year 24 Group’ and the shōjo manga revolution

In these extracts from the full article in Varoom 33 Zoe Taylor tells the extraordinary story of a group of pioneering young Japanese women who reshaped the comics industry and the wider culture, challenged inherited ideas of gender and revolutionised visual storytelling. Taylor also interviews Matt Thorn, whose English translations became a vehicle for popularising the work.

Huge twinkling eyes, splintered panels, abstract page layouts, androgynous boys, flowing hair, stars, flowers and melancholic longing…

These distinctive features of shōjo manga – Japanese comics aimed at junior and high school girls – crystallised in the early 1970s when ‘the Fabulous Year 24 Group’, the first wave of women artists working in the genre, elevated it to a new cultural prominence. Exploring philosophical, psychological and previously taboo themes with a unique sense of lyricism, they revolutionised the medium in works such as Moto Hagio’s The Heart of Thomas (1974-75) and Keiko Takemiya’s The Song of the Wind and Trees (1976-84).

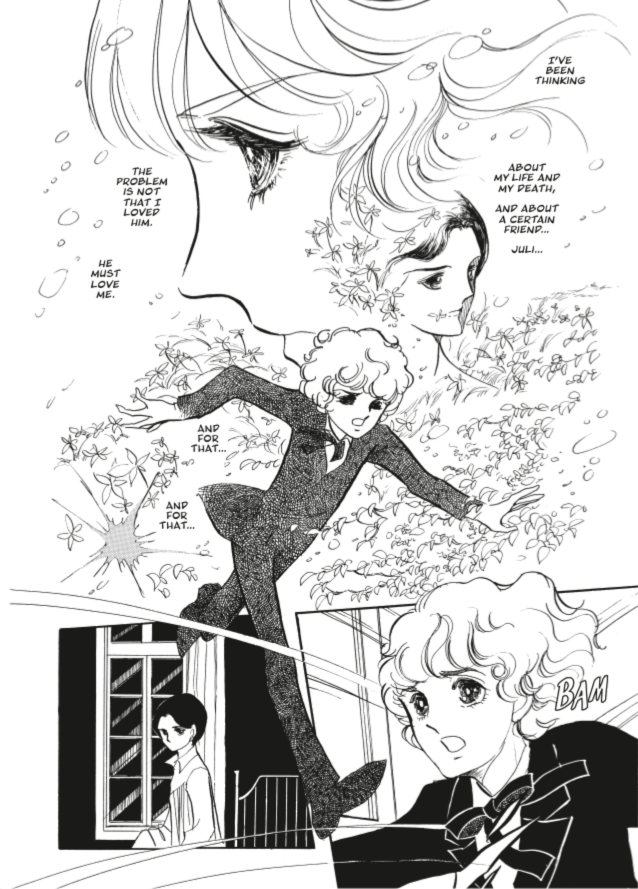

The Heart of Thomas, Moto Hagio, 1974-75

The Year 24 Group’s name refers to the 24th year of the Showa era (1949), which approximates the birth dates of the young women pioneers. It wasn’t a title that its members gave themselves and nor were they a coherent group: according to the translator Matt Thorn, the term includes anyone who contributed to the shōjo manga revolution. But Moto Hagio, Keiko Takemiya and Yumiko Oshima are always acknowledged as among the movement’s most significant artists. Born in the aftermath of the Second World War, these women grew up against the backdrop of the global youth counterculture of the 1960s and sought to transform manga into a new form of self-expression for women.

The shōjo comics of the Year 24 Group were primarily concerned with the emotions and inner life of the characters, an aspect that was heightened by major formal innovations such as the fragmented interior monologue. The abstract page compositions – which make liberal use of diagonal lines and montage-like arrangements – have been compared to Soviet Constructivist posters. Facial close-ups and action shots are densely layered with emotive shapes, allegorical imagery, expressive marks, psychedelic patterns, starbursts and screen tone, suggesting moments of melodramatic intensity.

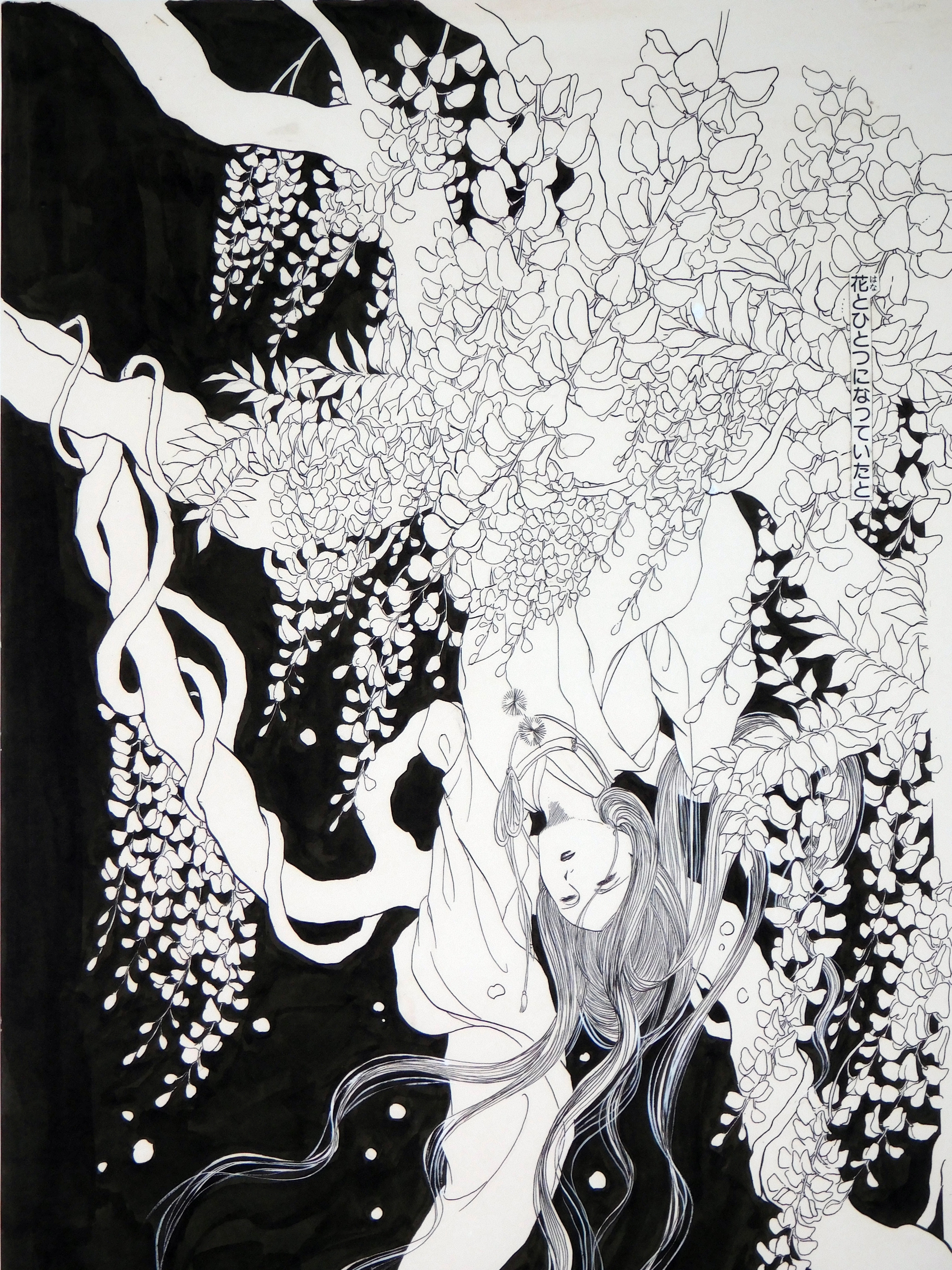

Fushi No Hana (An Immortal Flower) , Yukiko Kai, 1979

The decorative illustrations and dreamy jojōga (lyrical pictures) that had been developing in girls’ magazines since the 1920s also influenced manga. The art nouveau- and art deco-inspired fashion drawings of Jun’ichi Nakahara, with their elongated limbs and huge, long-lashed, doll-like eyes, were popular with teenage girls (Nakahara was also an amateur doll-maker). According to Thorn, when Yoshiko Nishitani wrote some of the first boy-girl school romances in the mid-1960s, she drew her characters in this style, which quickly became the convention. The manga historian Yukari Fujimoto writes that the exaggerated twinkling eye (which expresses emotion and encourages reader identification) was popularised by Macoto Takahashi in the early shōjo manga of the 1950s. Also inspired by Nakahara’s lyrical illustrations, he drew his characters with huge eyes and filled them with glittering stars. Others have attributed the exaggerated eye to Tezuka, who produced the first long shōjo manga, Princess Knight in 1953. Many Western writers assume that he was influenced by Disney, but Tezuka himself said that he was inspired by the eye make-up of the Takarazuka Revue performers, who were based in his hometown.

Cover for Nemuki magazine, Akiko Hatsu, 2001

Shōjo manga became popular in the West in the 1990s after the arrival of the anime series Sailor Moon, based on Naoko Takeuchi’s manga Bishoujo Senshi Sailor Moon. It sparked the American interest in anime, as well as inspiring a generation of girls to start reading Japanese comics. Deppey writes: ‘With its whimsical sense of fashion, thrilling adventure and complex backstory, Sailor Moon was like little else young girls had ever seen before on television.’ Although the English-translated shōjo manga market is still tentative, popular contemporary works have found a readership in the US.

The translator and cultural anthropologist Matt Thorn is an associate professor in the faculty of manga at Kyoto Seika University in Japan. She is currently editing a line of manga for Fantagraphics.

Zoe Taylor: How would you explain the sudden interest in shōjo manga in the US in the late 1990s? I’m thinking of the success of the Sailor Moon anime, for instance, and your translation of Four Shōjo Stories, which was published in 1996.

Matt Thorn: Before Sailor Moon came to the US (and finally succeeded after an initial false start), the conventional wisdom among the people in the toy and entertainment industry was that little girls wanted only fluffy, ultra-cute, strictly non-violent entertainment and that they stopped watching animation or (heaven forbid) reading comics by the age of ten or so. Sailor Moon turned that conventional wisdom on its head and did what I had been trying for several years to do: make shōjo manga popular with mainstream American girls and (eventually) women. I had been trying a top-down approach, translating titles that were sophisticated and geared more at women than at girls. Tokyo Pop (the publishers of the Sailor Moon manga) took the opposite approach, going after children who had not yet developed preconceptions of how girls should (or rather, should not) relate to animation and comics. I was trying to convert adults; they simply created a new generation that was open to the idea of comics and animation for girls.

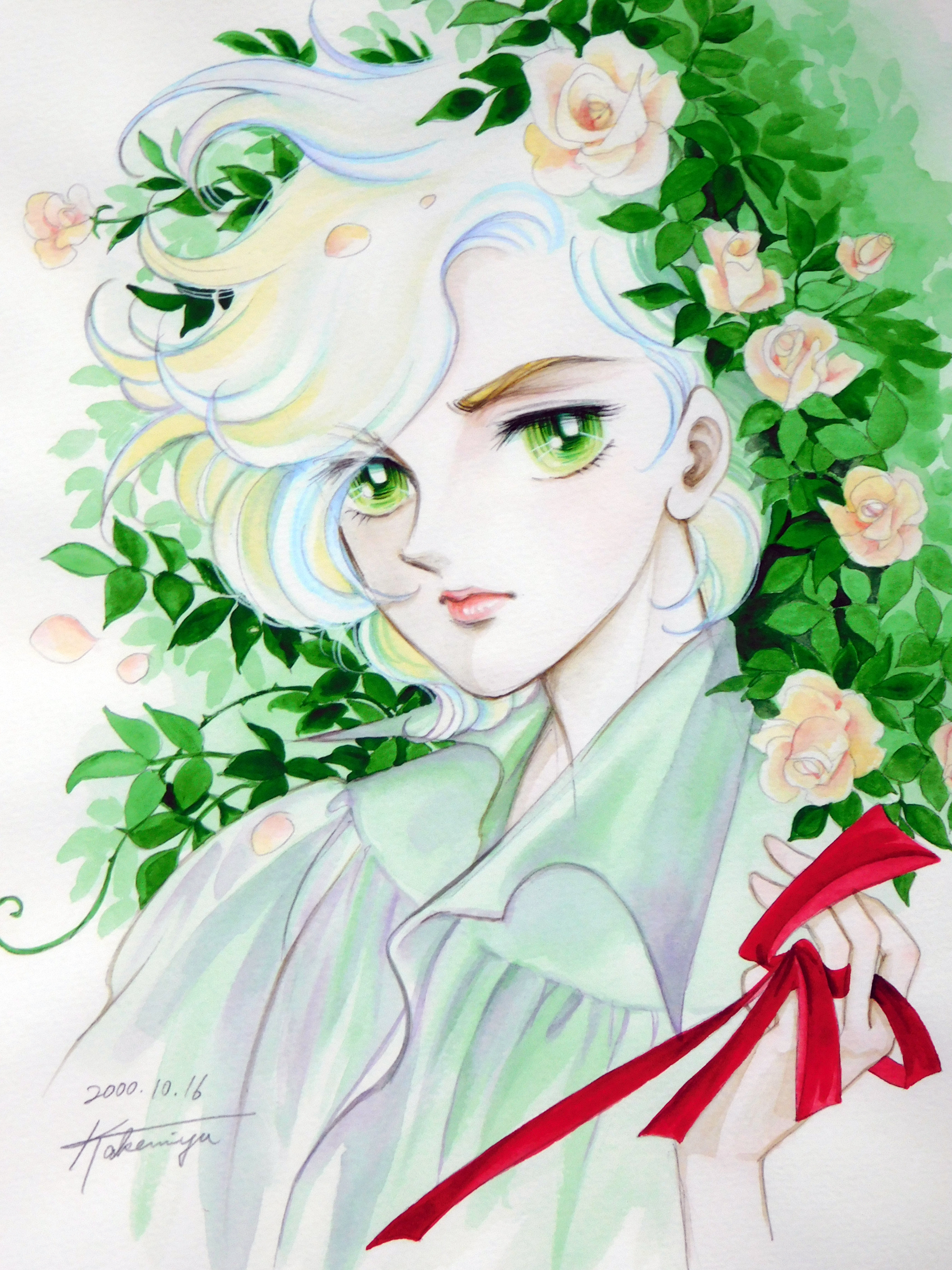

Bara no Toge (The Rose’s Thorn), Keiki Takemiya, 2000

ZT: Since then, has the work of the Year 24 Group become better known in the West?

MT: More fans are aware of the existence of the Year 24 Group than when I started evangelising back around 1993, but it remains the case that you can only read most of the manga those women produced in the original Japanese or in sketchy unauthorised translations. Sadly, there have been few authorised translations. Publishers are justifiably wary of translating ‘classics’ that may or may not appeal to wide audiences in the English-speaking world. There’s still a long slog ahead.

ZT: How would you explain the interest in gender and sexuality that pervaded their work?

MT: The Year 24 Group artists reflected the interests of then-young women of their generation. They were Baby Boomers, and had an interest in politics and social issues that later generations have not. ‘Women’s Lib’ was something they thought about and discussed seriously. They were frustrated and angry with a society that provided women with only a handful of acceptable life courses to choose from. They wanted to shake that up, or better yet smash it, and I think you could argue that they succeeded in some ways. They opened Pandora’s Box, and while Japanese patriarchy has fought against progress tooth and nail, Japanese women today have seen an alternative reality and cannot forget it. It was the Year 24 Group that showed them that alternative reality.

Moto Hagio’s Otherworld Barbara, translated by Matt Thorn, will be released by Fantagraphics this September.

The full article is in Varoom 33 the Collaborators issue, which is available here.

Back to News Page