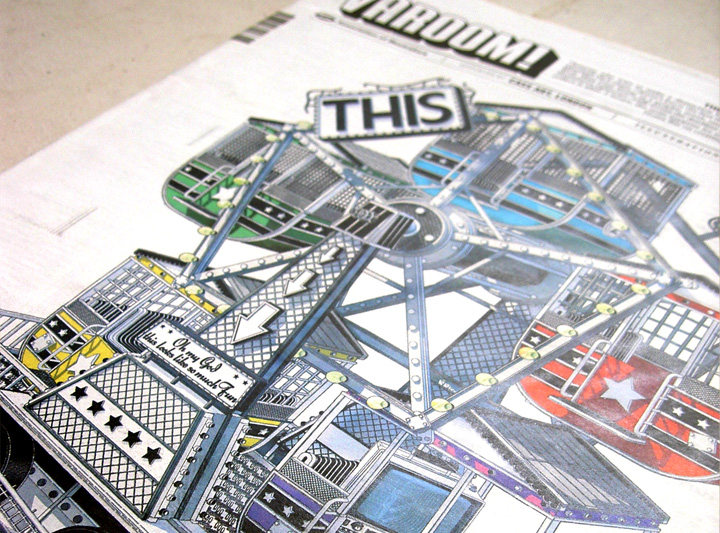

The Varoom Report: Entertainment V18

Entertainment

THE ILLUSTRATION REPORT Spring 2012

ISSUE 18

Issue 18 of Varoom celebrates the work of illustrators who entertain whilst asking questions about entertainment. From Moonbot Studios elagaic animation about books, to the BAFTA illustrators whose single images of movies act as illustrative film criticism, to cartoonist Huw Aaron who “performed” drawing at a cartooning festival. Plus the “architecture of things” – Stephen Walter invites us into Varoom 18 with his entertainment inspired cover. Editor, John O’Reilly’s introduction to this issue follows:

1.0 The Chicken as an Emblem of Distraction

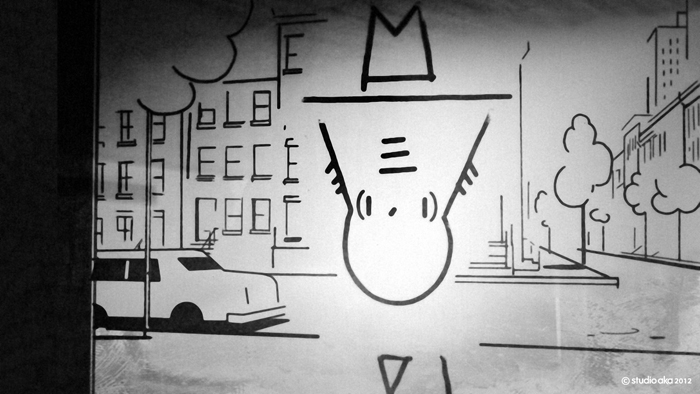

Writing this I got distracted by a story about a chicken. A film by animation director Grant Orchard, called a Morning stroll featuring a chicken in three different periods of time. The premise underlines how the character of the chicken, in jokes and stories, stands for distraction, like the question, “why did the chicken cross the road?”, a question born from the pleasure of distraction, how we love being lead astray by the daft and meaningless. The seven-minute long a Morning stroll is full of ideas, one of which is being attentive to the minutiae of everyday life.

Studio AKA, A Morning Stroll, 2012

1.1 The Cow who took on Facebook

Before I got distracted by grant Orchard’s chicken, I had been seduced by the dumb cuteness of some cow illustrations. This cow story is a satirical tale about entertainment and distraction. Ian Bogost, video games designer and academic, developed a game called Cow-Clicker. Developed for social play on Facebook, the game was incredibly simple. Players could click on a picture of a cow, and every time they did they got a point. They could click once every six hours (unless they paid) and could invite eight friends into the pasture to click the cow. Bogost drew a range of special cows, “premium Cows”, which players could buy with “mooney”. Every time you clicked a cow, a message would appear on your Facebook newsfeed – “I’m clicking a cow”. There were other elements, hard to call them subtleties, but essentially, that’s it.

1.2 How horribly wrong went horribly right

Cow-Clicker was a smart critique of games such as Farmville, which exploit users in various ways (you can read more about Bogost’s work by following the link at the end of this article). The black humour of Cow-Clicker is that that this fundamentally mindless game, a satire of mindless, joyless Facebook-type ‘games’, became incredibly popular, beyond those who saw its satirical intent. Like another piece of satire, Mel Brooks’ The Producers, the product which was supposed to go horribly wrong, went horribly right.

1.3 Cowapocalypse

As Cow-Clicker moved to its absurd conclusion with all cows disappearing into ‘heaven’ (raptured) in the ‘cowapocalypse’, Kotaku magazine games journalist Leigh Alexander relayed the interaction between Bogost and a player. The player asked when the game would be reset. “There’s no way to pay to see your cow,” replied the designer. “The cows got raptured.” When the user said he wasn’t going to play Cow-Clicker again because it’s “not a very fun game” any longer, Bogost replied, “It wasn’t very fun before :)”. The tragedy is that Cow-Clicker, with its drawings of premium cows, became a hit.

Greg Betza

1.0 Always-on mobile culture

This entertainment issue celebrates the creativity of illustrators, animators, graphic novelists and others who are showing the value illustration adds to brands, products and cultural forms. If the last decade of the 21st Century can be characterised as the beginning of the modern information age, the current decade, with the advent of always-on smartphone and social networking is the Age of distraction. Tweeting, texting, updating. One of the sections in a Morning stroll offers a wry observation of our mobile internet culture as a funky young city dweller misses out on a spectacularly odd event through being distracted by his smartphone. (Spoiler Alert! Anyone who saw the recent Mission Impossible 4 will have noted how the spy was killed as a result of receiving a text message which distracted him!).

1.1 Power & distraction

The idea of distraction has many shades. It’s always been at the heart of criticism of power. The Romans called it Bread and Circuses, believing that entertainment was distraction as a political strategy. When Karl Marx called religion the opiate of the people, it’s a political comment on how we distract ourselves with ‘drug-like’ activities. And there was the criticism which merged philosophy and Fine Art in the writings of people like german political philosopher, Theodor Adorno, who believed popular mass entertainment was at best an escape from our miserable working lives, and at worst degraded our ability to grow as human beings with richer lives.

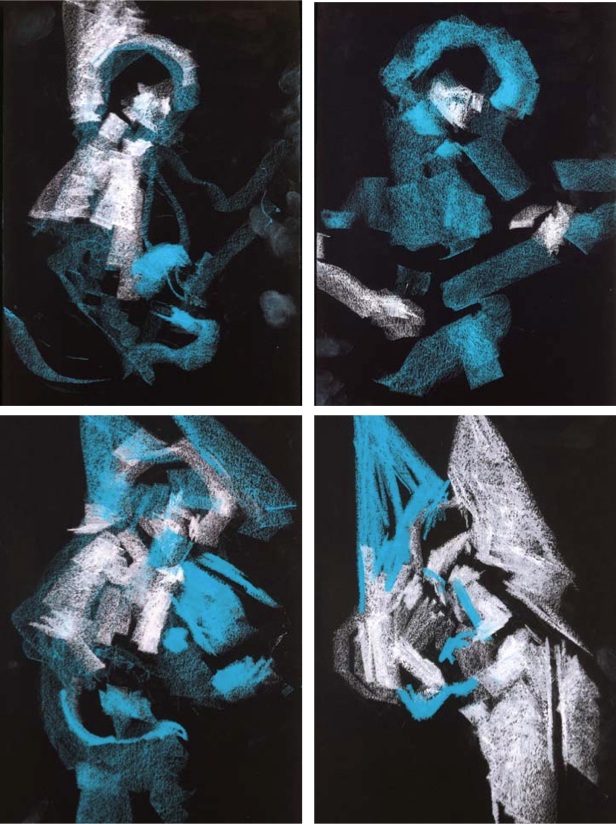

1.1 Storytelling, collage & illness

There is a tradition of seeing distraction as a kind of social illness. Freud, whose Wolf Man case study as graphic novel we feature, sees psychological illness as the work of distraction. We distract ourselves through the various symptoms we create to protect ourselves, which prevent us from being able to tell our own life stories properly. Slawa Harasymowicz’s jagged, disrupted, visual narrative shows Sergei Pankejeff’s distraction by the dream image of the wolves. But in the digital age with our constant flows of information, offering more personalised customised experiences, tweet updates, social network updates, and deeper ‘engagement’. As new technologies have got better at capturing our attention, illustration is getting better at generating a richer kind of distraction, redefining distraction itself as an escape route from the kinds of entertainment that are more prescriptive of our experiences and seek to limit them.

Slawa Harasymowicz’s The Wolf Man

2.0 Drawing time

As children, drawing, making pictures, connects boredom with the desire for distraction and entertainment. Tolstoy defined boredom as “the desire for desire”. Anyone taking care of kids know they define it more pragmatically – “what can I do next?” As children, creating a distraction, a diversion for your self, is about creating a space for ourselves, creating a self, with our own self-generated distraction. It’s no surprise that the app, Draw something, generated 50 million downloads in 5 months, as it squared the circle between locking onto that unembarrassed pleasure in drawing with a desire to connect with others. Or the huge popularity of Marion Deuchars’ Let’s Make some Great art, with its cheeky cover of a cropped version of the Mona Lisa, peering over the bottom of the page and a cute little chick standing by a pencil. Finished off by the hand-painted lettering which conjures up the feel of a fun, time-passing, rainy-day project.

2.1 The Doodle as Swiss Army Knife

Illustrating the boredom of everyday life is a skill we all master for ourselves over time. Officially, it’s called a doodle. The doodle (see Bill Prosser, and Des McCannon, on the doodle Varoom issue 10) “aids concentration by soothing the mind”, wrote Des McCannon in issue 10. Doodles soothe us from a lack of desire, from that frustration. The doodle is illustration’s own Swiss Army Knife for every type of boredom: a survival tool for distracting ourselves from the different boredoms of modern life: the organisational meeting; the boredom of our own thinking; the boredom of having too much; boredom as the absence of meaning in life in general, a sense of a lack of purpose; the boredom with clients wanting the same image (“just like you did for Brand X!”).

2.2 Save us from “Nothing”

Like Laurence Zeegan’s provocative essay on contemporary illustration in the March issue of Creative Review prompted by David Shrigley’s (bored) illustration displayed outside the Hayward gallery – a clenched fist alongside the slogan, “Fight the nothingness”. An engagingly daft slogan, yet “Nothingness” in Fine Art has always been associated with a certain kind of art. Art critic Brian O’Doherty made the distinction between High Boredom Art such as Op art and Pop Art with its busy optical effects and Low Boredom Art, that recedes into the background. Although pop artist Andy Warhol’s serial art was the apex of boredom and Warhol himself was the connoisseur of boredom. The “Nothingness” prompted Zeegan to ask questions about the limitations of contemporary illustration, illustrators’ lack of interest in wider social purpose, or the ability of the Pick Me Up graphic art show to speak to a wider audience than the illustration groupies like myself who turned up at the Somerset House venue in London. Are we bored with the status quo?

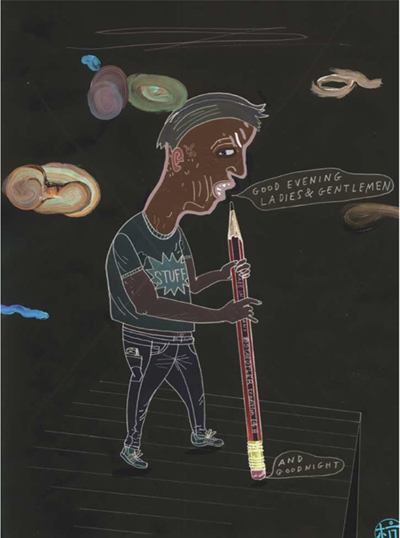

1.1 Minor detail and the Art of Boredom

In different ways both Shrigley and our own Paul Davis are propelled by the aesthetic of boredom. The artlessness of the drawing, the hyper-awareness of aesthetic, cultural and social convention, which like the bored teenager comes from a keen bullshit radar. Because it is an intense experience of the moment, that’s why boredom is so boring, it’s an inability to envision a future, being submerged in the moment. Observational illustrators like Davis, his boredom with life and art’s clichés, makes us laugh at our own, boring, comforting habits of mind. The Art of Boredom expresses itself by paying attention to the small, supposedly insignificant minor details of life.

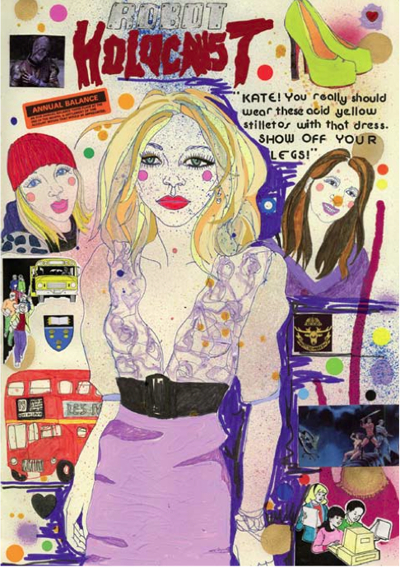

2.0 Distracted Expressionism

Sarah Beetson’s series of prints at the Somerset house Pick Me Up displayed that unique teenage emotional state that mixes emotional intensity, desire with the utterly distracted and bored – “OMG!” plus “Whatever…” Sometimes boredom is ‘affected’ a defense mechanism, sometimes it’s about ‘cool’. If there is a emotional spectrum of teenagehood, its visual languages of the school copybook are fashion and typography, the doodle of band logos, guitars, clothes, expressive lettering pulled together from whatever comes into the view of the young person reaching for ideas of adulthood. Robot Holocaust (above) typifies Beetson’s B-Movie art, with an object of admiration and desire in the foreground surrounded by top-of-mind distractions, the school bus, crests, homework on the computer and the splashes of bright colour (a feature of Paul Davis’ work) that turns the macho drip and splash of Abstract expressionism into absent-minded drops and beauty spots. Let’s call it distracted expressionism, playful and scrap-bookish.

1.1 Open-ended distraction

What distraction and boredom have in common is that they are open-ended. They’re not directive, don’t prescribe how you use your time, or direct your thinking. Unlike the majority of current gaming apps on social network sites, the app by Moonbot for The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr Morris Lessmore, with pictures and puzzles and games allows the viewer/player to discover the games themselves. Pure distraction discovers its own points of interests, things that catch the eye, places to park itself. When asked how he keeps his ideas fresh Peepshow’s Miles Donovan replied, “New ideas come out of boredom most of the time.” Philosopher Walter Benjamin would agree, “If sleep is the apogee of physical relaxation, boredom is the apogee of mental relaxation. Boredom is the dream bird that hatches the egg of experience.” From this perspective being bored is much closer to being in a dream state.

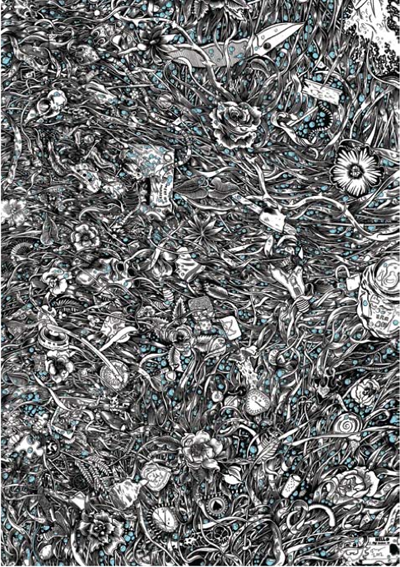

1.1 Lost in detail

Getting lost in the detail is a pleasure of distraction. Like in Tim McDonagh’s Petrichor print at Pick Me Up (above). He brings to his image-making, a kind of American gothic, an extreme figuration that lends itself to the viewer getting lost in the minutiae, staring at the lost objects in the grass, these lost objects points of departure for imaginary stories. Petrichor showcases McDonagh’s interest in layering ‘reality’, to distract the viewer through a camouflage of line and colour. The boredom of staring brings rich rewards.

2.0 Oppressed by the “interesting”

Boredom is essential to creativity, to the imagination, to developing a sense of discovery. “how often, in fact,” observes psychoanalyst Adam Phillips in his essay Being Bored, “the child’s boredom is met by that most perplexing form of disapproval, the adult’s wish to distract him – as though the adults have decided that the child’s life must be, or seen to be endlessly interesting. It is one of the most oppressive demands of adults that the child should be interested, rather than take time to find what interests him. Boredom is integral to the process of taking one’s time.” Boredom is a privilege of youth.

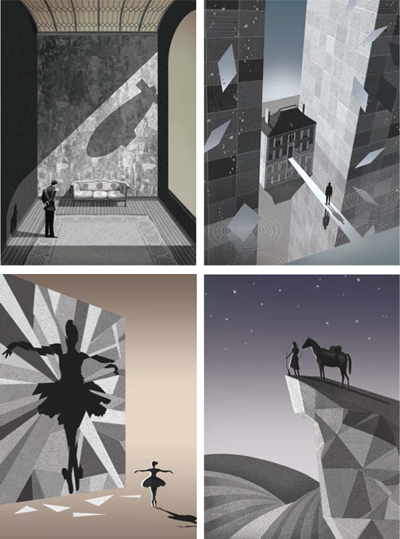

1.1 Looking again

One of my colleagues described Adam Simpson’s images for the BAFTA awards as “slow”. It’s an accurate descriptor of images that go beyond the frozen moment of the still image captured from a film, that reach into the film’s psychological and emotional engine. Simpson’s BAFTA images position the viewer with dramatic wide-screen perspective that offers a new interpretation of the film. Makes you look again at something you thought you knew.

1.2 Vitality of distraction.

We need to rediscover the pleasure and vitality of boredom and its companion, distraction. In a world where it seems the future has already been set in stone by politicians, bankers, cool-hunters, who tell us how the future is supposed to be, we need the creative and professional wit of the illustrator to take us somewhere else. Like Cachete Jack, the Spanish illustration duo, Nuria Bellver and Raquel Fanjul, who showed at Pick Me Up, whose Crisis Oh! Really? expressed with black humour the social mood of Spain in 2012. The humour of the their naïve style subtly distracts us from the pointed politics of their observations, their wry visual notes on the chirrupy, confident, clichés of conformity. Great illustration, whether it’s children’s books such as The Great Flood (pg 26) or The Ride Journal (pg 50) which wraps its devotion to the extraordinary detail of cycling with rich imagery, which brings me back to the chicken… Why didn’t the chicken cross the road? Uou’ll have to watch a Morning stroll to find out.

To purchase Varoom 18 go here

Back to News Page