Serena Katt, The Raw And The Cooked, #1 Graduates 2013

In a work of compelling honesty, new RCA Graduate Serena Katt explores her Grandfather’s time in the Hitler Youth.

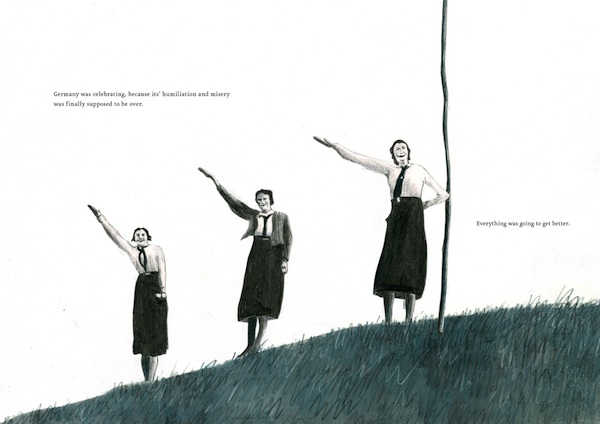

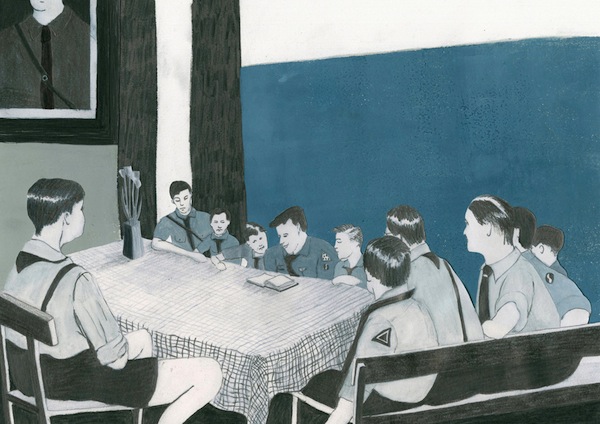

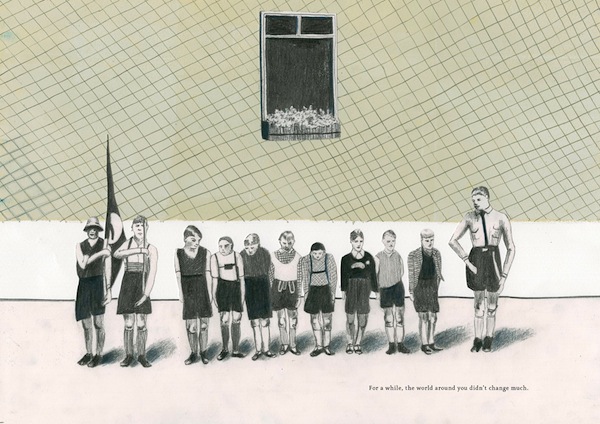

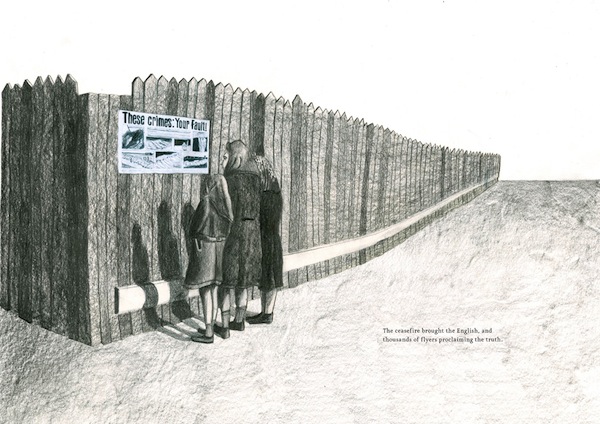

Over the following weeks we’ll be exploring some of the work that made us think a bit differently about illustration in 2013. Today we’re looking at Sunday’s Child, a book by RCA Graduate, Serena Katt, a visual narrative examining her Grandfather’s boyhood as a member of the Hitler Youth.

Varoom: Materials, Format and Name of Work?

Serena Katt

Materials: Mixed media. I apply block-printing inks with a roller to create textured backgrounds, collage pencil drawings over the top, and use watercolour pencils to add colour details.

Format: Book (17 x 24 cm), original illustrations 34 x 24 cm.

Name of Work: Sunday’s Child.

Addressing your Grandfather’s time in the Hitler Youth, was “Sunday’s Child” an emotionally difficult work to create?

Serena Katt: I don’t know if difficult is the right word. I was very emotionally engaged in the subject, otherwise I don’t think I could have sustained the project for a whole year, but I can’t say I found it hard or unbearable to learn about. I was fascinated, and still find it so unbelievable that that whole period of German history happened, that I was just spurred on by wanting to learn more. I spent a long time researching the subject, and in doing so I found out more about the brutality inflicted on and encouraged in these young boys in the Hitler youth, which is something no one really speaks about. Some of the eyewitness stories I found were very difficult to read and hear, especially when thinking of my Granddad as being one of these young boys. But it’s hard to know what my Grandfather himself really experienced, as his notes on this time were very scarce.

What is the history of the photos you used and how difficult was it to construct a coherent narrative from it?

Serena Katt: Most of the photographs are taken from German archives and distorted, cropped and altered slightly to fit the narrative. A few also come from the photo albums of my grandparents. The narrative is pieced from different elements – my Grandfathers notes, other eyewitness accounts of the time, these photographs and my own words. I began by making research drawings from all the photographs I had found, searching for the story through drawing. Once I had established what angle the story was going to be told from, I began writing the story while continuing to draw, so one was always informing the other. Sometimes I’d be looking for a particular image to go with a piece of text, at other times I had an image that I knew needed to be in the sequence, and then found the words to go with it. It felt like a natural, almost collaborative process between drawing and writing.

Your use of collage and photographs lends the images a kind of adolescent awkwardness. Is this an aesthetic treatment you use in all your work?

Serena Katt: It’s not an aesthetic that I have ever aimed for, but people have made that observation a lot about the way I draw figures. When I draw, I try to lose any idea of what it will look like before I begin, and react directly to the reference material I am working with, so I guess the awkwardness in these figures relates to how I felt about the boys in the photographs.

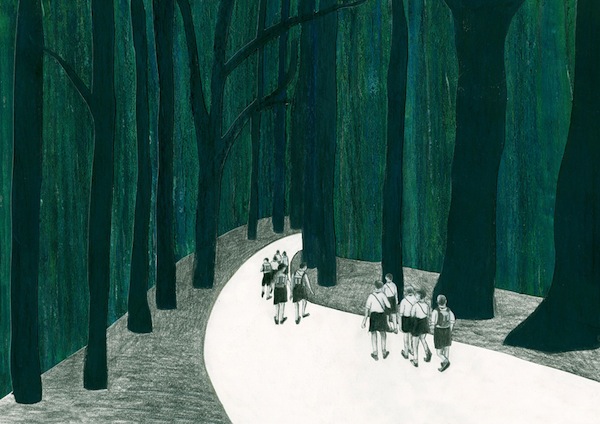

What’s fascinating about your story is that it because it is often wordless, the reader gets to experience the visual and physiological aspects of Nazi mythology – the boxing, the swimming, a cosmic philosophy of health and nature? Did you always want to create wordless story?

Serena Katt: There are words in parts, but I’ve used them very sparingly. The narrator is me, and the book is really a letter to my Grandfather. But the words I am using aren’t entirely mine, they borrow heavily from the Nazi propaganda of the time, and from the words my Grandfather used to record these memories.

The central sequence of the boys’ journey through the forest to the Nuremburg Rally Site is wordless, to allow the reader to enter into this almost fantastical boys world. For the rest, I wanted to create several narrative layers within the story. One layer describes what these boys and my Grandfather experienced, using the language that they would have used to describe their activities. Another is directly borrowed from the Nazi propaganda, and is the voice of Hitler that draws them on this journey to the stadium. The third layer is the images, which show a different, darker view of the story, which sometimes differs from the words.

The notes my Grandfather made don’t go into much detail, and what he has written makes everything sound fun, adventurous, and almost like any boys’ experience of the boy scouts. But of course there was a lot more going on around him. I was particularly interested in these omissions, because I think they are quiet telling of the psychological repercussions of the training he and all his generation were put through. There are all these layers of guilt that factor into the way Germans who lived through it remember this time, which results in people censoring themselves and their memories heavily. There is guilt for the concentration camps, obviously, but also a guilt for having enjoyed growing up during this time, a guilt for having loved Hitler, for being devastated at Germany’s defeat etc. etc. So it is very difficult to get at any real memory or real feeling about this time.

There’s one extraordinary image of the young members of the Hitler Youth at the very top of the amphitheatre at Nurnberg. The perspective feels like a comic-book image, you feel the rush of these young teenagers, you sense their sense of awe – there is a psychology here. What’s compelling about the book, and makes it more credible and scary is that the visuals don’t take sides. How did you manage to keep such an even sense of tone?

Serena Katt: I’m really glad that this comes across. I was absolutely aiming for an unbiased view of history. I think people have spent too much time in the past either defining people as victims or perpetrators, and it was really important to me to start looking differently for myself, to look at the individual within that mass of history, and to relate to them as a human, not as ‘a German’ or ‘a Nazi’ or as ‘the defeated’. I think there is a lot of new, exciting discourse about Germany’s relationship to its past appearing at the moment (for example, the amazing TV drama “Unsere Muetter, Unsere Vaeter”), which takes a much more open approach to questioning and examining German history, without labelling from the outset, so that definitely inspired me.

Were you anxious before showing it to your grandmother or family?

Serena Katt: I am anxious about showing my Grandmother, yes, and also my great Aunt, my Granddad’s sister, who I interviewed as a part of my research. They haven’t seen it yet, and I’ve no idea what they will think! My parents are as interested in the subject as I am, and very open about discussing it, so I’ve shared a lot of the research and my writing with them as I’ve gone along.

Next steps with the book? Next steps for Serena Katt?

Serena Katt: I would love to publish the book, both in an English and German speaking market. So I’ll be doing the rounds to publishers in the next months! Otherwise, I just want to keep on working. There are lots of images that didn’t make it into the book that I still want to work with, so perhaps another narrative will emerge. Otherwise, I just want to keep making images and telling stories within whatever context comes along next.

Back to News Page