The Bibiliophile: by Derek Brazell

Audrey Niffenegger, who spoke at the Boundaries Illustration conference in September 2012, is not only a best-selling author of The Time Traveller’s Wife. She reveals to Derek Brazell her other life as a maker of artist’s books, and her part in a vibrant culture of Chicago bookmakers.

The scent of a new book’s paper is one of the pleasures readers often describe on beginning a new volume. It’s the start of a journey of what can develop into a strong bond with a piece of storytelling. This connection can expand to further levels with a handmade artist’s book where the paper itself, the binding properties, as well as the images and text make a tangible, sensual object, both physically and intellectually engaging.

The work of artist and writer, Audrey Niffenegger, is closely connected to the book as a connector of people, an indicator of a character’s personality, a repository and expander of knowledge and an artefact. She has explored many properties of bookmaking since her college days in the 1980s and became closely involved in the Chicago bookmaking scene from the nineties on, embracing the physical properties of book making whilst also weaving books and reading into her writing and artworks.

She began exploring the construction of books as a young teenager, trying to work out how a book could be made from scratch. “All my early books I made with rubber cement,” she remembers, “and they looked terrible!” These would often be accordion fold books with stiff card interiors with the card and drawings glued in. Rubber cement, she ruefully recalls, being far from an ideal archival material.

Studying printmaking, photography, drawing and painting at the School of Art Institute in Chicago betweeen 1981 and 1885, she started producing the prints that would make up The Adventuress book. Following sketches and storyboarding, these images were created as aquatints, and though she wished to find some teaching on typesetting and book production – ‘I was trying to imagine how it might have been made’ – it was not until her final semester that she was able to join the heavily subscribed book binding course run by Joan Flasch, ‘So it was kind of DIY, which was alright.’ At this point, with her final show in mind, Niffenegger made a set of flats, in addition to the two sided prints for binding, which allowed the ‘book’ to be exhibited on walls. She built this into subsequent work, aware that her artist’s books need the opportunity to be observed in a space additional to the book format, ‘One of the hardest things with books is displaying them in a way that either allows people to interact with them, or protects them. There’s this tension between handling and wear. So I feel I’ve solved that by letting the books exist in a deconstructed form, and go on the wall without any touching.’

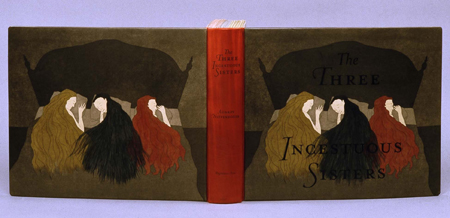

The Three Incestuous Sisters origional handmade book, created over a 14 year period

Hands on experience

Previous projects had included hand rendered text, but The Adventuress had to look like a ‘proper’ book. Although loving ‘zines, Niffenegger did not want her book to look like them, and eventual access to a letterpress allowed her to place text on the page in a convincing manner. Though a novice, research into older letterpress printing became confidence inspiring, as she realised that not all of it was to a high standard. Following college, Audrey studied bookbinding privately with Heinke Pensky-Adam, learning skills she felt should have been taught at college. This absence in her education fuelled her motivation, when later involved with a book arts programme to ‘make it a really good one. With some actual knowledge.’

A second visual novel, The Three Incestuous Sisters, ‘a melodrama of sibling rivalry,’ followed the college project The Adventuress, though this one took 14 years to complete. Only finally being finished when Niffenegger’s gallery scheduled an exhibition of the work two years hence to ensure a deadline.

The handling of a physical artist’s books can enhance the response for the viewer, and their tactility and construction separates them from published books – the texture of the paper, density of ink and variety of binding materials. But Niffenegger has experienced a certain reticence from some people, who might say ‘Shall I put on gloves? How do we do this?’ And I’m, like, ‘It’s a book, open it up’. They are meant to withstand handling, but there’s almost this barrier where people have been taught not to touch art, and somehow this isn’t a book, it’s art. And there’s a real weird thing you have to overcome with people.’ The handmade version of The Three Incestuous Sisters is ‘massive’ with 3.5 inch margins around the prints, on thick paper, ‘You couldn’t put it in your lap – it’s got this big wingspan.’ The margins were removed for the published version, of what is still a sizable volume. Although this may be the expectation, Niffenegger emphasises that artist’s books are not required to be gorgeous and amazing, and that sometimes ‘crappy’ is just what you need. This can be the appeal, especially for people who encounter them unawares, ‘What’s that? That’s odd, let’s pick it up’. And if you can get someone to pick it up, and actually engage with it,’ she continues, ‘then you’re home free, because then they’ll keep going. Especially if the person is intellectually curious, they’ll take it on almost in the spirit of playing a game.’ She acknowledges that her own books are not in this area, ‘But with some of the more conceptual books you really need people to engage with the thing.’ Not least with the occasional concern that with books of unfamiliar structure they may not be able to put it back together.

Image from The Three Incestuous Sisters. ‘A firecracker in a baby carriage!’

A major element of the appeal of these types of books is something shared by both creator and reader, the evident control that that the artist has over all specifications. With published books the various areas are parcelled out among many people, but Niffenegger sees that the artist’s vision is contained with their own creation, ‘So the person who’s encountering it has a complete experience made by one person, or however many people are involved with it.’ Although machines can make good books, she observes that ‘People definitely sense craftsmanship,’ and she stresses that she is drawn to flaws. With her own work ‘there is always something about it that’s half cocked, because I like that. I don’t want it to be smooth.’

The transition from limited edition handmade book to the published version formed a shift in Niffenegger’s relationship with the book. On first receiving The Three Incestuous Sisters from her US publishers, even though she’d had input into the design of the book, it did not feel right to the touch – flat and thin. The physicality of the volume had changed. ‘Then after handling it more, handling the limited edition feels odd! Just through using the commercial editions of the book a lot more, the realness of it has somehow shifted over into that.’

Before The Adventuress or The Three Incestuous Sisters were commercially published, a shared passion for crafted books had brought together several organisations in Niffenegger’s home town of Chicago to form the Columbia College Chicago Center for Book and Paper Arts. There were a couple of very small organisations in Chicago, Artists Book Works, founded by Barbara Lazarus Metz, and Paper Press, a papermaking studio and gallery run by Marilyn Sward. Niffenegger remembers both organisations being ‘incredibly scrappy!’ and she worked for the Artists Book Works for a short time. They had a letter press and offered classes in typesetting, bookbinding, printing, and the making and exhibiting of artists’ books, though she recalls that there was little money and the equipment was ‘semi broken.’

Exploring directions

A more successful organisation, made up of the top book conservators and binders in the town, was the Chicago Book Binders, who did not have the need for a physical space as they did not run any programmes. They met in a bar to have drinks and chat about books, and Audrey joined in, meeting binders Richard Weaver and Tricia Hammer, who had the idea there should be a more comprehensive and glorious book arts organisation in Chicago. This evolved into a plan to find a wealthy sponsor, as had happened with the Minnesota Center for Book Arts in Minneapolis, but Marylin Sward heard about the plan and offered to join Paper Press to the venture. She set about approaching educational establishments, and to their surprise Colombia College said yes. Part of Niffenegger’s impetus to create a strong book arts school came from the lack of teaching knowledge in this area when she had been searching for guidance during her time as a student in the eighties. This was now 1994, and Colombia, a private school, was the ideal institution to take on this scheme from a mix of book lovers. Barbara Lazarus Metz eventually also folded the Artists Book Works into the Center, so these separate small organisations now became part of a common aim.

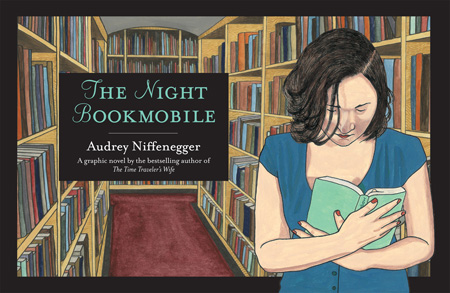

The Night Bookmobile published by Jonathan Cape (UK) and Abrams ComicArts (USA) 2010. Originally serialised in The Guardian newspaper (UK) during 2008

The diversity of the people involved ensured the Center never formed a house aesthetic, allowing the students to explore their own directions. Niffenegger taught as Assistant Director (one of a staff of two), enjoying the position of being able to equip the students with the skills needed and then sending them off to ‘make of it what they will.’ Many of the early students were graphic designers, drawn to the hands on techniques, and approached the subject with different outlooks. Years on some are now teaching at the Center, a direct lineage from the enthusiastic participants of the early nineties.

Niffenegger now teaches fiction writing at Colombia College, but continues to develop her artwork. The recently published graphic novel, The Night Bookmobile, was developed from a short story written in 2004, when the Guardian newspaper in the UK asked her to create a serialised comic in 2008. Guardian Senior Designer, Rodger Browning, had met Niffenegger whilst she was in London and she had mentioned that she had an idea for a graphic novel. ‘We leapt upon it,’ he says, ‘It sounded perfect for us,’ as the newspaper’s previous comic serialisation, Gemma Bovary by Posy Simmons, was coming to an end. When initially contemplating the project, Niffenegger felt a little trepidation, ‘I love comics, I think about comics a lot. I’m kind of a comics imposter,’ but she resolved to try and make her comic look like a comic – ‘I’ll get in there and give it a go.’

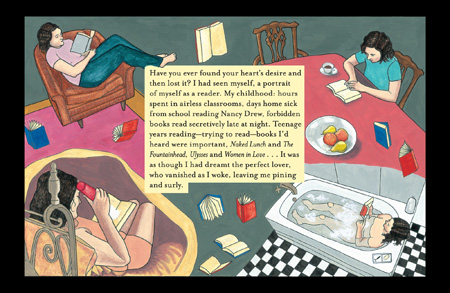

This involved a shift away from printmaking to gouache, a favourite medium to paint with, via an unusual way of proceeding with a comic. Audrey had a precise idea of how the panels should relate to each other, so once storyboarded and reference photos were shot she laid it out in InDesign, including all the narrative text, and printed out to start drawing on. As, untypically, printed text was already present she then had to find a solution to combiming this with the image. This ‘bizarre typographical thing,’ as her publisher later referred to it when it came to printing a bound version after the Guardian serialisation, resulted in a painted fade into the image around the text. This was later replaced with more conventional text boxes for the book version. Niffenegger had been dubious about this change, feeling that working with type and image on one artwork ensures they are fully integrated, ‘you gain something, that the reader isn’t distracted.’ She also incorporated her own handwriting in the characters’ speech bubbles, though was asked as to why she had done that. ‘I’m all about the idiosyncratic, and even though I wanted to do a real comic, I didn’t necessarily want to subscribe to every convention. As long as it’s enough like a comic that people can use their knowledge of comics to look at it, I think it’s OK.’ Having said that, she has an expectation that a comics readership will be more critical than a fine arts audience may be, observing that ‘A lot of the traditional criteria for what is ‘good’ have survived in the realm of comics. Good drawing, good storytelling – does this person have good technique …it just doesn’t apply to fine art’

The Night Bookmobile interior image, published 2010

Books and reading form an important theme within Niffenegger’s writing. It feels significant that Alexandra, the main character in The Night Bookmobile, discovers her first childhood diary on the shelves of the bookmobile. How much stronger a connection with a book can there be than with a diary? Unique to an individual, this type of volume was chosen by Niffenegger to prompt Alexandra’s realisation that the bookmobile she had just entered on a late night street held everything she had ever read over her whole life. ‘I had seen myself’, the character contemplates later, ‘a portrait of myself as a reader.’ The titles that Niffenegger selects in her writing for her characters – Naked Lunch, The Moonstone, Lord Of The Rings – can be ones that she considers favourites herself, or ones that are appropriate for the character, ‘I can’t give something to a character unless I know about it, even a little bit. In this one in particular, everything that Alexandra mentions I have read, and usually loved.’

While uncertainty hovers over the publishing world as the future of the physical book faces up to digital devices, it’s appears inevitable that the artist’s book will remain as a tangible expression of a desire to create. And even though Niffenegger expresses concern over avenues current publishing is exploring, ‘If comics go heavily into the electronic realm I think it will change comics culture. A lot. I don’t know if people want to go there or not,’ the step into digital books may increase the value attached to different expressions of the book. As she comments on the Center for Book and Paper Arts, ‘We seem to have tapped into a thing where people want relief from their computers. They want things to really exist in physical space, and they want to put their hands on them, and they want to make. When the computer does it for you, it seems a little cheaty.’

Audrey Niffenegger is also author of two novels, international best-seller The Time Traveller’s Wife 2003, originally published by MacAdam/Cage, and Her Fearful Symmetry 2009, published by Scribner (USA) and Jonathan Cape (UK). The Night Bookmobile is out now.

Back to News Page