Quentin Blake – The House that Quentin built

Quentin Blake is arguably Britain’s best-known and most loved illustrator, feted for his iconic work for children, from Matilda’s Miss Trunchbull to Mr Magnolia his current work surprisingly illuminates life at the other end of the age spectrum. Jo Davies visited his studio for Varoom in 2009 and discovered Blake also had a new job, as the virtual architect behind the world’s first centre dedicated to illustration. Davies’ article from Varoom 11 is reproduced in full here.

Is part of Blake’s ambition to elevate the cultural status of illustration? “That’s part of the philosophy of the House of Illustration,” says Blake. “Certainly it’s mine. It isn’t necessary to elevate illustration, but to give it its true value.”

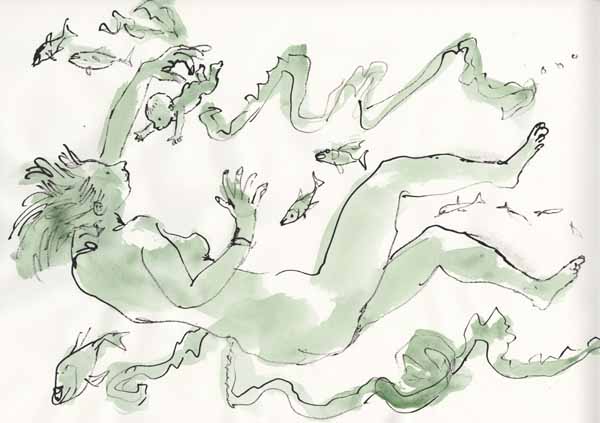

Swimmers: One of a series for the Gordon Hospital, London, 2009

Some people think of museums as mausoleums, displaying odd artifacts, historical relics, that have been dug up and polished. When Quentin Blake in 2002 laid the foundations for what has been intelligently branded the House of Illustration it wasn’t conceived as simply an archive of old illustration. “Exhibitions will look at what has happened in the past, what is happening in other countries at the moment, and what might happen next.” Importantly he “wants it to be a very alive kind of institution” to re-define the museum experience.

Currently a virtual museum, the website intersperses works from the likes of contemporary observation- based illustrator Laura Carlin with political satire from Cruickshank. Its activities are peripatetic, its exhibitions on the move, but the greater ambition is to establish a permanent base, a tangible House of Illustration. The location, which will locate illustration firmly on the cultural map, is a Victorian house in the King’s Cross redevelopment area. Notwithstanding the current economic climate, acquiring such a building requires considerable equity, the target being £6 million, with £10 million cited as the true sum needed to get the project moving.

One of a series for the Gordon Hospital, London, 2009

That there isn’t a National Museum devoted to entirely to illustration reveals the struggle illustration perennially faces to assert itself as a credible player in the arena of popular culture. Is part of Blake’s ambition to elevate the cultural status of illustration? “That’s part of the philosophy of the thing,” says Blake. “Certainly it’s mine. It isn’t necessary to elevate illustration, but to give it its true value. Also there is a huge amount of imagery, which nobody knows about, which nobody ever sees.”

Blake’s commitment to bringing illustration to a broader audience has been demonstrated as curator of several high profile exhibitions. Magic Pencil organised by the British Council in 2002, celebrated children’s picture books. The original exhibition of art works toured six European venues, the facsimile exhibition continues a tour of 50 countries and 171 venues.In All Directions, curated in collaboration with National Touring Exhibitions, featured artists from across three centuries. Blake showed that illustration could be a vehicle for social, cultural and historical knowledge, “You can present a subject, which everyone knows about,” he explains. “This was about transport, about travel, about cars, trains and motorcycles. The exhibition also provided you with a kind of history of illustration and of the reproduction techniques of the time. You get that mesh. There is a broad educational function, and a school educational function.”

Changing the perception of illustration

The House of Illustration plans to show works from major collections, challenge boundaries, and cover all genres of practice. Based on a Victorian parlour game, the most recent show What Are You Like? emerging under its auspices, currently on tour nationally, features an eclectic mix of both contemporary illustrators and celebrities with a creative leaning, providing a ‘self-portrait’ composed of their favourite things.

There is no global definition of what constitutes illustration, nor agreement on its value. With it’s broad agenda realised through workshops, events and exhibitions The House of Illustration may contribute to remoulding of perceptions of the subject globally or at least extend the debate about the position illustration occupies relative to other creative disciplines. “There’s a sort of aura of mystery about Fine Art,” he argues, “a convenient leftover from Romantic notions about genius.” Blake backs up this view with an anecdote. “Twenty years ago,” he remembers, “I had to deal with everything that was left in the studio after Brian Robb died. He was a good painter and illustrator, and I went into this gallery to see if the Director was interested in Brian’s paintings, and he said, ‘When I hear the world illustration…’, I thought he was going to say ‘I reach for my revolver’. But he said, ‘I blanche’, or something like that. The extraordinary thing was that on the wall were pictures by Paul Nash, Edward Burra, Peter Blake, – he was running with people who were both good painters and good illustrators!”

Quentin Blake

Blake is synonymous with the education and entertainment of children. Globally there exist more than three hundred books which he has illustrated. He spoke about his tangential involvement with the DCSF. “It’s popularly known as The Department of Curtains and Soft Furnishings, and stands for Department for Children, Schools and Families or something like that. It would have been the Ministry for Education at one time. We did a day with teachers, talking to them about how they could use illustration. I think they’ve come to understand how you can use what may look like younger picture books at an older age – ten and eleven. You can look at them from the point of view of pictures, of interpreting them as works so to speak. It’s not right to think simply in terms of literacy. But if we are talking about literacy, it’s hard to overstate the effect of motivation that pictures give – the urge to live a story in words as well as pictures. I get the impression that this is an aspect of learning to read that quite a lot of people in education haven’t yet grasped yet.”

There are few illustrators who, like Blake, have been awarded a CBE. That he is regarded as a bastion of excellence in children’s publishing is shown by the multiple accolades with which he has been honoured internationally. Notably he became the first Children’s Laureate in 1999. As a natural tangent to illustration it is well documented that Blake has been instrumental in establishing the Campaign for Drawing, which highlights the value of drawing through its national events.

Characters as archetypes

Merchandising through greetings cards, games and stationery has contributed to the expansion and assertion of “Quentin Blake “ as a ubiquitous brand. For many, however, it is the collaboration with Roald Dahl which lends recognition. The many characters depicted have been adopted as archetypes for childhood, a visual repertoire of goodies and baddies; a child’s worst enemy manifest in the warty Miss Trunchbull from Matilda. Here Blake rejoices in the grotesque. His images are imbued with emotional content, pathos, which resonate beyond the meaning of the text. “The words are there,” he says, “but you can sometimes bring something out of it that’s not contradicting it. It’s not that it isn’t in the book; it just helps it out somehow. I think some of the pictures are more introspective than the words. There is something you can contribute because you read the character’s feelings off the paper.”

Drawing Blake created for the Scarborough Hospital maternity ward, 2009

Blake showed me the drawings he is currently creating for the Scarborough Hospital maternity ward, featuring floating ladies gently clasping their curious offspring who have just been endowed with new life. These are the latest in a chapter of work, which as Blake says doesn’t have a genesis in books-work positioned in or out of buildings (banners, murals, large-scale vignettes) a lesser known aspect of his creative output. “When they opened St Pancras station,” explains Blake, “there was a rather scruffy building opposite. They couldn’t pull it down because it had a preservation order on it. They said ‘what can you do about it?’ I was working with a House of Illustration friend and he said, ‘all we can do is wrap it’. I did a drawing, which might have been a double-page spread in a magazine, and it’s now five storeys high!”

Blake is a patron of the Nightingale Project, a charity that puts art into hospitals. Since 2006 he has created many images for hospitals and health centres in London and France. “It’s pictures I’m defined by, really I think. I’m much more inclined to think that pictures can have an implied narrative much more than many people do nowadays.” These latest projects are not linked directly to a literary narrative. They deal with themes, which have gravity of meaning to us all – life and death, the trauma and insecurity that surround illness and ageing, and these images are threaded with metaphors, conveying complex meanings, shown in settings often alien to us and fraught with drama and emotion.

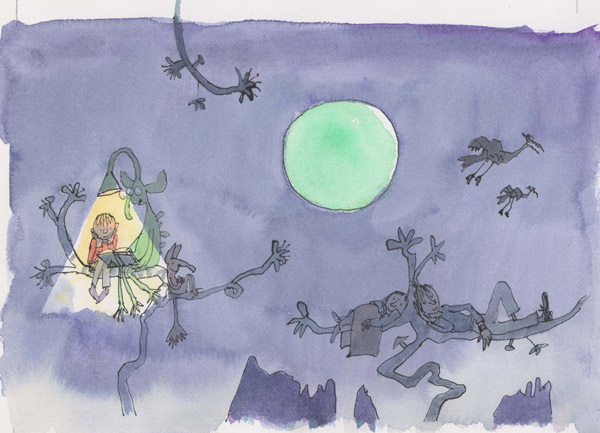

The concept of the ‘alien’ literally takes shape in Welcome to Planet Zog at Alexandra Avenue, Harrow, and a series of murals in the waiting room where curious looking extra terrestrials have fun in the playground. In parallel, enmeshed in the visual language are associations of familiarity, which Blake brings, a source of comfort in situations and surroundings otherwise uncomfortable and alien to young children. “A mother came in with her child,” he says, “who knew what they were immediately. She thought they were for Roald Dahl, they’re not exactly quite the same, but the recognition still seems to be there.”

Reading at Night from the Welcome to Planet Zog series. For the adolescent unit at Alexandra Avenue, London, 2007

Although this work may seem like a divergence in context, scale, and format, it continues to radiate the vitality and freshness that signifies Quentin Blake’. Removed from a story or text the newfound scale is an exciting dimension of it, the viewer is more aware of their pictorial qualities. Swimmers is a set of 15 giclee prints in the corridor of the Gordon Hospital, a mental health care hospital in Victoria, depicting people swimming, rather strangely, fully-dressed. These brush drawings have a lovely freedom of line: a distinctively Japanese feel. Blake has also created drawings for the mental health centre for older adults at the South Kensington and Chelsea Mental Health Centre. The surprise of these images is part of their appeal. Witty, not patronising, they “celebrate the art of ageing”, his characters engaged in a fanciful cavorting in monumental trees.

The notion of valuing age and enjoying life is revisited in a set of images called Our Friends in the Circus created for an elderly patients department, in Northwick Park. Here he employs a mature cast to occupy roles from the circus; flamboyant characters including fire-eaters and jugglers. He says it’s a parallel fictional world picturing what he himself would like to be doing.“I project myself into an extension of what we all do anyway,” he says, “everyday life, but transferred into a situation where one can do it with more flexibility, vivacity and invention than you could do in real life.” Whether in his work for The House of Illustration, through his practice as author and illustrator, or his hospital projects, just like the characters from Our Friends in the Circus, Quentin Blake continues to possess flexibility, vivacity and invention in abundance. There are great trees outside his studio too.

The pictures in Kershaw (the elderly people’s ward in South Kensington and Chelsea Mental Health Centre) form the basis of You’re Only Young Twice from the Andersen Press.

Varoom 11 can be purchased here

Quentin Blake website

Back to News Page