Posy Simmonds on the challenges of picture books

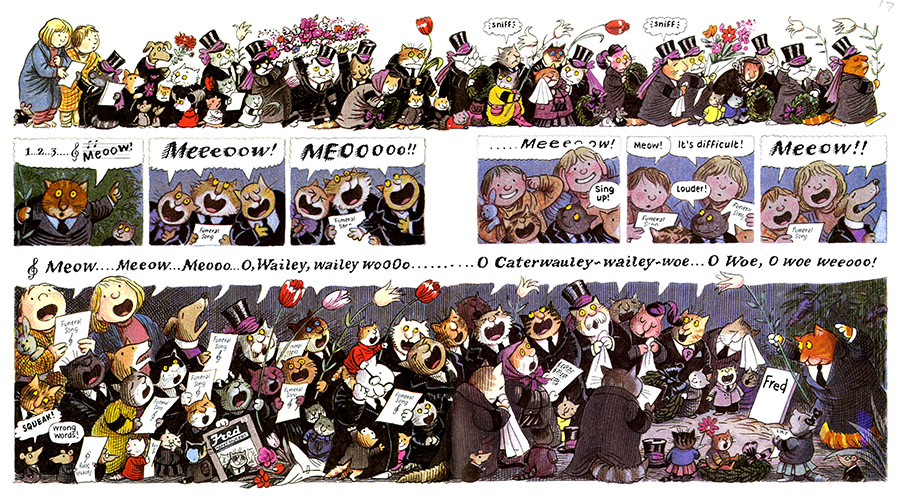

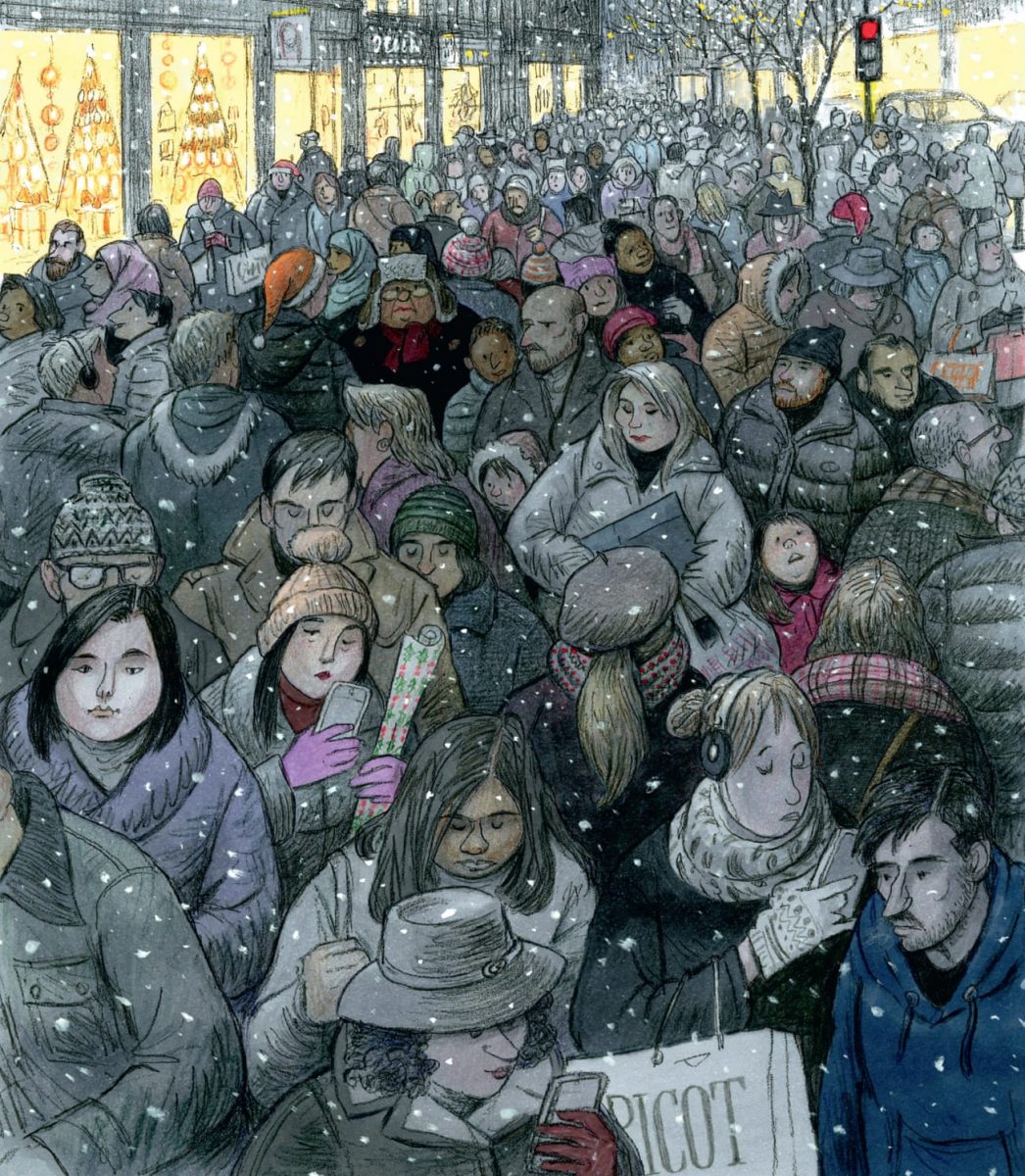

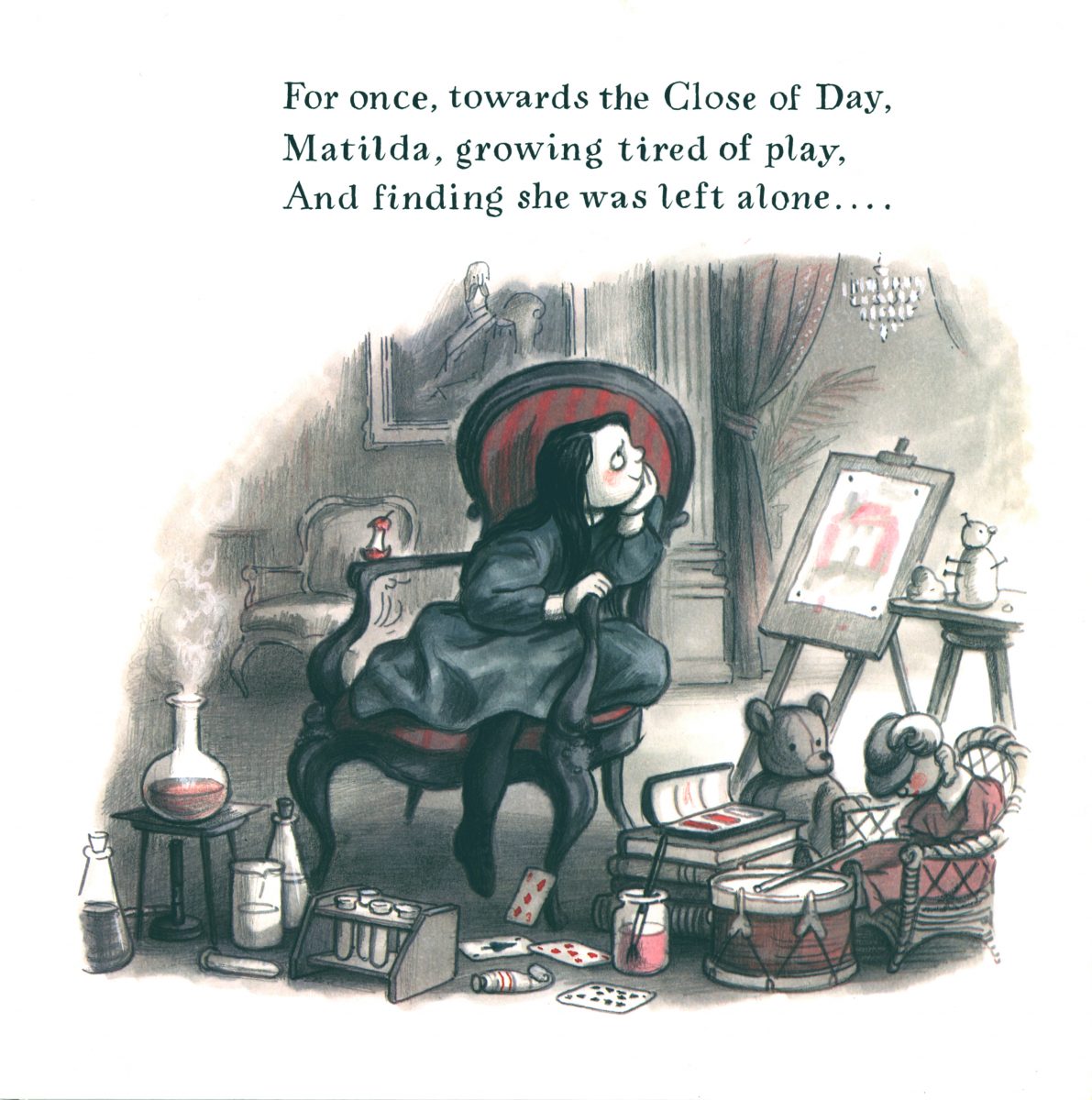

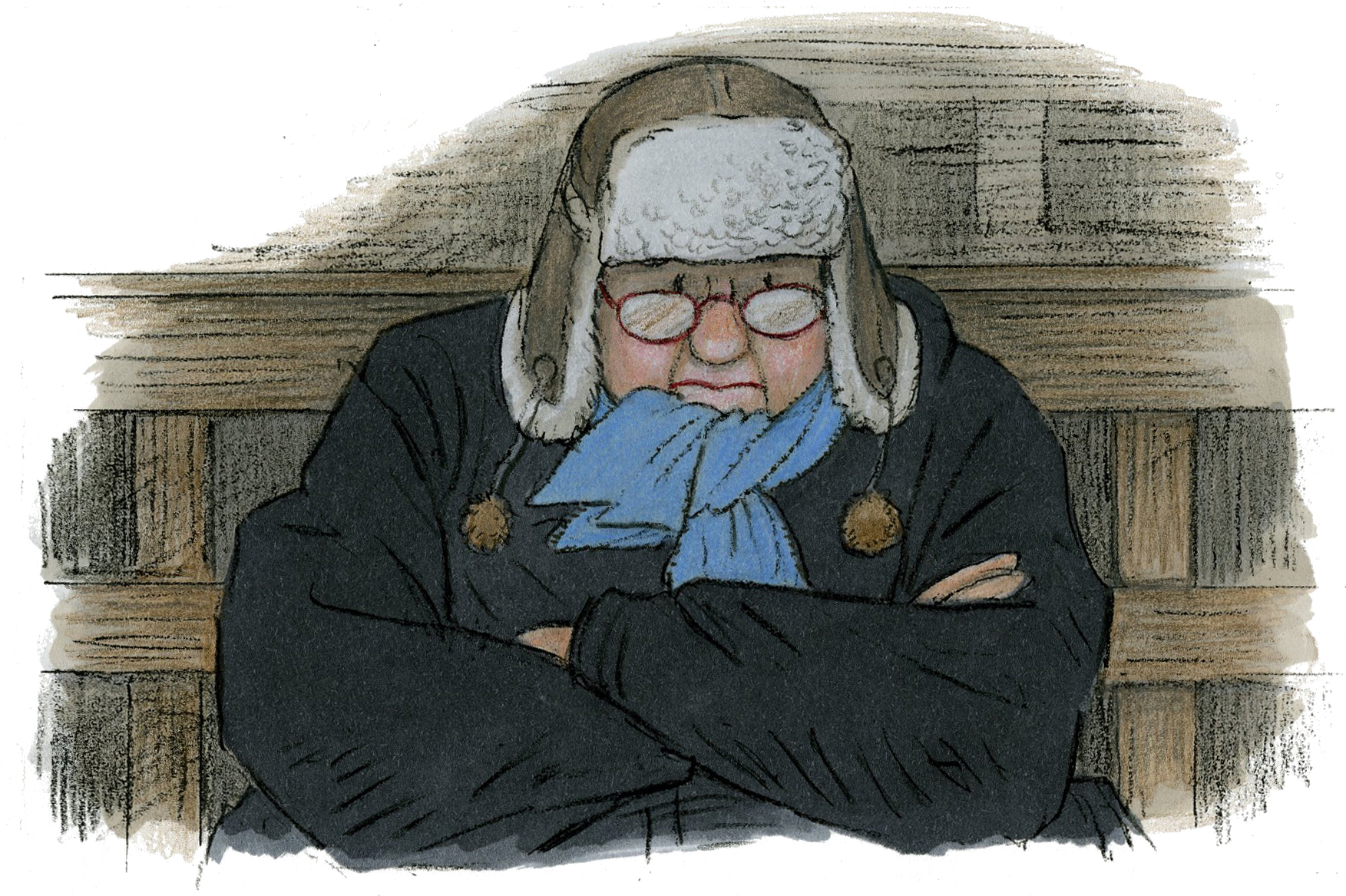

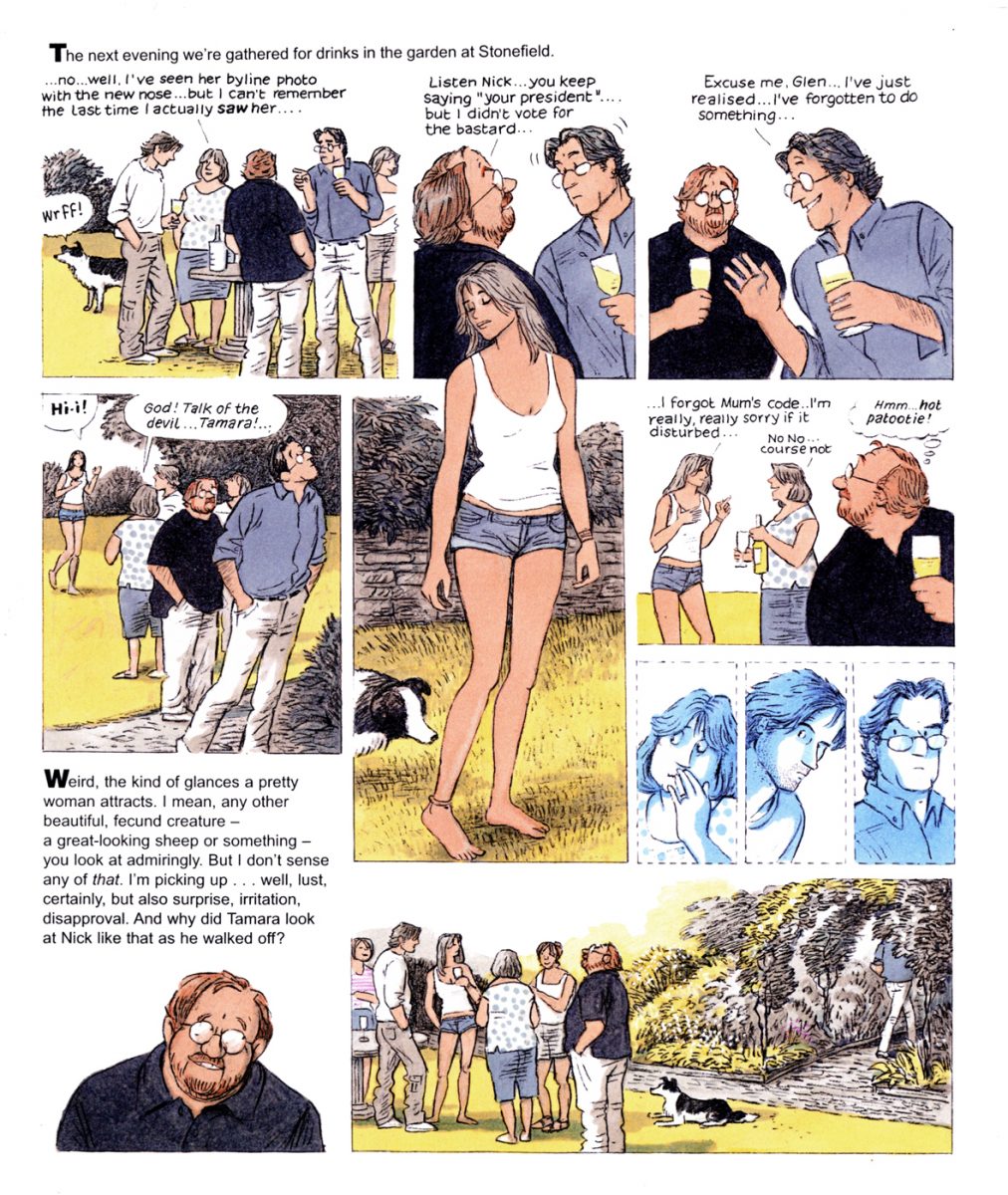

One of this year’s Klaus Flugge Prize judges, Posy Simmonds has been described by Paul Gravett as ‘simply one the world’s most sophisticated contemporary cartoonists expanding the scope and subtlety of the graphic novel’. She is famous for capturing character and nuance in her graphic novels and comics, which include Gemma Bovery and Tamara Drewe – both of which started as strips for The Guardian newspaper. She has also created children’s books, including Fred and Matilda Who Told Lies and Was Burned To Death.

An excellent choice for the Klaus Flugge Prize judging panel, which awards the most promising and exciting newcomer to children’s picture book illustration, Posy took time to tell as about the challenges for visual storytellers and how rhythm effects her work. Check out the impressive Prize Shortlist.

What do you believe the challenges are for visual storytellers?

Posy: An important challenge is the number of books published every year. This includes children’s books by celebrities, which get promoted at the expense of real authors. (This is not to ignore certain celebrities who write terrific books).

Everyone embarking on a picture book will want their story to be original and to stand out among the many. They’ll want each spread to be a visual surprise, the text to work for reading aloud and the story to begin, build and end in a satisfying arc. Easier said than done.

Several children’s book illustrators I’ve talked with have said that their publishers have grown more cautious than in previous years and that the sales team have more say in choosing books than the editors. This makes for a “safe and tried” formula, rather than more adventurous ideas. And bright colours rule, because “bright colours sell.”

Picture books and graphic novels are long term undertakings – do you think illustrators and those writing their own texts need to have a tenacious focus?

The creative process for picture books and graphic novels is rather like that of making a film. The writer/illustrator becomes not only script writer and director, but also Casting, Costumes, Continuity, Props, Location, Lighting and Special Effects. There’s the same period of “pre-production”, where important decisions have to be made – the characters’ appearance, their personalities, the setting and pace of the story and so on. The story (the script) has to come first and is the most important thing to get right. The most magnificent illustrations can be undermined by a weak story, badly told. Picture books are generally 24 or 32 pages long, much shorter than graphic novels, which can run to hundreds of pages. This is where patience, energy and a “tenacious focus” are really necessary.

Rhythm is an important part of storytelling in pictuer books and graphic novels. How do you consider that in your work?

I’m conscious of rhythm. Past work has included strips of 3 panels and 15 plus. The same rhythm happens whatever the number…first the set up, then the development and then the pay-off. It’s a bit like joke telling, man goes into bar, barman says X, man does Y.

The story/plot of a picture book or graphic novel obviously works to a final denouement. Two of my graphic novels appeared first as serials in The Guardian. Serial form gave the story a different rhythm. In order to engage the readers, each episode had to end on a cliff-hanger.

Your work has recently been selected as one of the ‘200 moments that made The Guardian‘ newspaper on it’s 200thanniversary – which of your own project you are most proud of?

Gemma Bovery was probably the most difficult thing I’ve done. Everything I learned from it made the later graphic novels easier to do. Gemma Bovery was commissioned by The Guardian, to run daily in 100 episodes. I’d been used to drawing strips in a horizontal space, but the format I was given was long and thin, 3 columns wide by the depth of the paper. It was a format I later grew to like, as it was versatile and could be chopped into varying layers. Being used to working quickly to deadlines, I had done about 25 episodes when the serial started. This was rather rash, as my rate of drawing could only just keep up and by the end I was only 4 or 5 episodes ahead. A hairy ride, which at the same time sparked ideas – ideas which often refuse to come when one has time to vegetate.

Is it satisfying to see what you’ve achieved over your career?

I recently moved house and cleared out my rather messy workroom. Some of my work was quite satisfying to see again. And some of it made me think Why did I use so much black? Wish I’d changed that word. Very wonky drawing of her arm! Why is it that roughs are so much better than the finished drawing? ….

See the Klaus Flugge Prize Shortlist.

Back to News Page