LOL! Politics of Humour Pt. 1

Immigration, gun control and social justice issues. With politics firmly in the headlines both in the UK and USA, Varoom talks to four pioneering US image-makers about how the political cartoon is evolving.

For a generation of people, the caricature on the newspaper Opinion pages was a brisk corrective to what was perceived as the outrages of politicians and governments. But in an age when the printed newspaper is either closing or transitioning to digital, how is the political cartoon evolving? In a frank and provocative series of interviews published in Varoom issue 29, four exceptional US image-makers – Molly Crabapple, Jen Sorensen, Liza Donnelly and Mark Fiore – talked to us about the changing forms and contents of the political cartoon in the 21st Century,

Jen Sorensen and Molly Crabapple are below. Read about Liza Donnelly and Mark Fiore in part two.

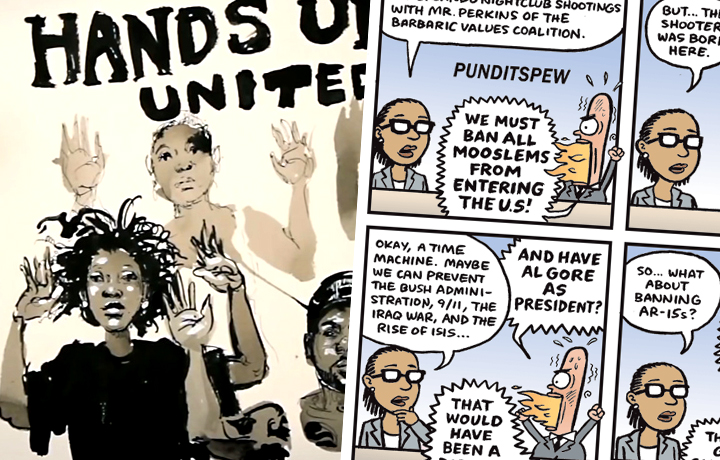

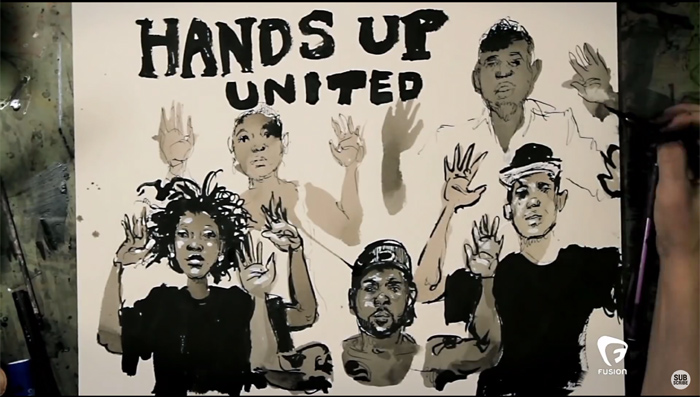

Molly Crabapple

Molly Crabapple is an artist and writer in New York. Her memoir, Drawing Blood, was published by HarperCollins in November 2015. Called “An emblem of the way art can break out of the gilded gallery”, by the New Republic, she has drawn in Guantanamo Bay, Abu Dhabi’s migrant labor camps, and with rebels in Syria. Crabapple is a contributing editor for VICE, and has written for publications including The New York Times, Paris Review, and Vanity Fair. Her work is in the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

Your bio page says you have taken your “sketchbook from burlesque halls to refugee camps, always with a skeptical eye for power”. Do you think a younger generation has a different concept of the political/power than perhaps the one we are familiar with on Op-Ed pages?

Do Op-Ed pages speak to anything but other op-ed writers? Was there ever a young generation that listened to the ketamine-addled word hallucinations of Thomas Friedman?

How much has working with Vice magazine shaped your take on politics?

Not a single iota.

You’re a writer as well as image-maker. To what extent does your sketchbooking and image-making practice refine your political ideas, how you see things? Whether that’s the human interaction with people while sketchbooking or the reflection in creating an image?

Drawing is a fundamentally different interaction than photography. Often, people view cameras with suspicion – as an opaque black box that captures their images, which will profit the photographer but possibly endanger them later. Drawing is more of an interaction. When I sit with someone and draw, they can see what I’m doing, and tell me how I’m failing. We’re on more equal terms. That sense of being on equal terms is the basis of so much of my politics.

In the context of politics and power, who are your influences? Do you have any influences in your aesthetic and approach from traditional satire?

Toulouse-Lautrec all they way. Every poster is about class war and cynicism as much as it is about a can-can girl’s petticoats

How did you arrive at the aesthetic groove and storytelling form for your animations?

Me, Jim Batt and Kim Boekbinder have been working as an animation team for years. Our first piece was an elaborate paper puppet stop motion short called I Have Your Heart. Jim, the director, constructed streets, docks, and gardens out of my drawings, even cutting out thousands of individual ivy leaves. It’s exquisite, but it took three years. We developed the stop motion sketchbook style doing animations for the Royal Society of Arts, and then refined it, and made it more detailed, emotional and violent, to tackle the topics of police and prison violence for Fusion.

In essays on topics such as Google Glass and Photoshop your writing explores the boundaries of the political/technological/aesthetic. To what extent does new technology drive new ideas of the political?

We live in a time where people have the most ability, in the history of the world, to speak to each other across borders. Yet, the security of physical borders is so brutally enforced that immigrants are dying in boats in the Mediterranean. The internet is a place of almost gnostic freedom where your most intimate thoughts are spied upon, that’s used to constrain your physical actions in ways the despots of yesteryear could never have dreamed.

Which particular work of yours has had the most impact?

Probably an essay I wrote about my own abortion. Hundreds of women wrote to me to thank me, including women who had gotten illegal abortions in Northern Ireland.

The future of political imagery?

There’s no “the” future of political imagery or of anything else. Multiplicity, that’s the future.

Follow Molly Crabapple @mollycrabapple and mollycrabapple.com

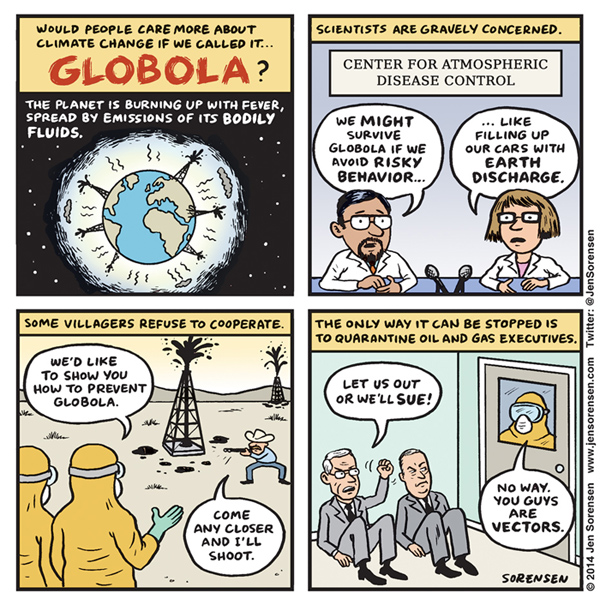

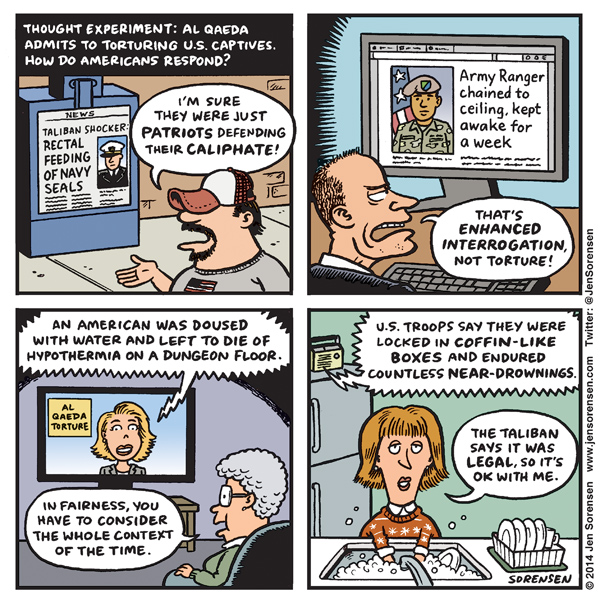

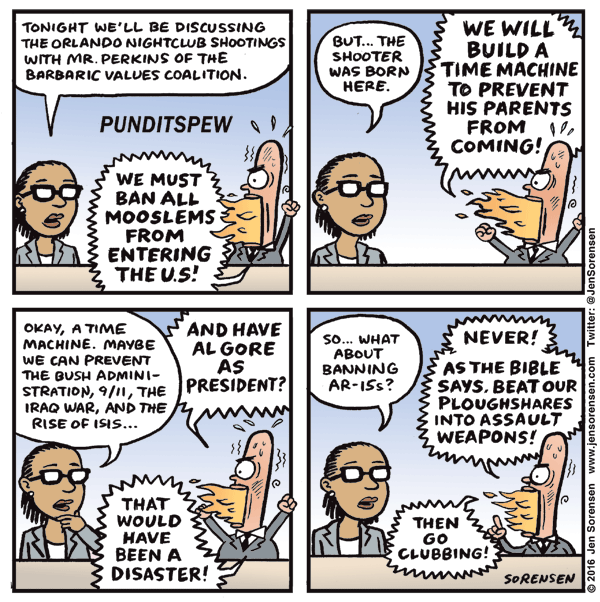

Jen Sorensen

Jen Sorensen’s comics and illustrations have appeared in The Progressive, The Nation, Ms. Magazine, Politico, Daily Kos, AlterNet, MAD, Nickelodeon, Los Angeles Times, The Austin Chronicle, The Village Voice, The Book of Jezebel, and dozens of other publications around the country. She has created commissioned long-form comics for the American Civil Liberties Union, NPR, Kaiser Health News, The Oregonian, and other clients.

Varoom: You originally studied cultural anthropology before becoming a cartoonist – how do you think it shapes your vision of the ‘political’? And how did it develop your image-making practice?

Jen Sorensen: I feel that studying cultural anthropology prepared me well for becoming a political cartoonist. It gave me an excellent framework for understanding the world. Like political cartooning, it’s all about observing human behavior. Knowing that most of what humans do is culturally-constructed and not necessarily the only way of doing things helps you imagine how life could be different. As far as drawing is concerned, it’s something I’ve always done since I was a kid. I was self-taught, without formal training save for a few art classes here and there.

You started your weekly strip in 1998; what was its format and what was it about?

When I started the strip, the format was similar, but the humour was more surrealist than political. That started to change with the disputed election of George W. Bush and the catastrophes that followed. Those years turned a lot of not-so-political artists political.

You do a lot of work around “women’s” issues (which are obviously also men’s issues!) and feminism. Was this always a feature of your work? Do editors get in touch with you to deliver images around this kind of political content? I’m thinking of your recent image for Jessica Valenti’s piece on TED Women or the NPR books’ Pride and Prejudice project.

You do a lot of work around “women’s” issues (which are obviously also men’s issues!) and feminism. Was this always a feature of your work? Do editors get in touch with you to deliver images around this kind of political content? I’m thinking of your recent image for Jessica Valenti’s piece on TED Women or the NPR books’ Pride and Prejudice project.

Yes, I’d say commentary on gender has always been part of my work, even going back to my more surrealist days. One of my earliest characters was Drooly Julie, a woman with an outlandishly large libido. Editors do seem to reach out fairly often for work concerning women’s issues, which I’m happy to do, although sometimes I wish they would try just as hard to reach out to female artists for work on other topics.

Could you tell us a little about The Book of Jezebel?

JS: The Book of Jezebel was put together by Anna Holmes, founding editor of the well-known feminist website Jezebel. It’s a pretty amazing encyclopedia of women’s history and pop culture – very educational and funny. Anna hired a number of women illustrators to contribute to the book, and I was fortunate to be one of them.

How has the demise of print media and the rapid acceleration of new media – smartphones, social media, platforms such as Twitter – impacted on the ‘political’ cartoon?

The switch from print to digital has been a mixed bag. On the one hand, it’s been scary, and in some cases disastrous, for those dependent on print publications. As recently as five years ago, the vast majority of my income was from print. On the other hand, the rise of digital has allowed my work to be shared more widely than ever, and has opened up new opportunities. More websites are paying for comics now; this positive development along with my editing job at Fusio n.net have allowed me to make the transition, even as I still rely on print altweeklies. In the digital age, you need to be more diversified and entrepreneurial as a cartoonist. Of course, this is more easily said than done.

n.net have allowed me to make the transition, even as I still rely on print altweeklies. In the digital age, you need to be more diversified and entrepreneurial as a cartoonist. Of course, this is more easily said than done.

Could you tell me a little about your role on Fusion? And the kind of work it features?

Fusion is a startup media company owned by Univision and ABC News aimed at diverse young adults. They have both a digital component and cable TV channel. I edit a comics section on the website called Graphic Culture. We publish political cartoons and graphic journalism. Recently, I drew my own longform comic sharing the story of a friend of mine who was raped in college – that got a huge response, making it one of the most popular posts on the site.

The future of ‘political’ imagery?

Political cartoons tend to do well on digital platforms because they are so shareable. In the years ahead, I think you’ll see a greater variety of formats, especially more long-form nonfiction work and multi-panel comics. You can do cool things with animation too, although I don’t see that replacing static images. Single panels are actually perfect for Twitter, so I don’t see those disappearing, although drawing styles will likely evolve from the traditional daily newspaper aesthetic.

Follow Jen Sorensen @JenSorensen and website jensorensen.com

This article concludes in Part two, featuring Liza Donnelly and Mark Fiore.

Back to News Page