Interpretation: The Designer Toy Platform

DARWIN / The Designer Toy Platform as a Means of Academic Inquiry

Justin Novak, Associate Professor, Ceramics, Illustration, Visual Art and Material Practice

Director, Centre for Applied Art and Material Production (CAAMP) Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver, Canada

Key Words: Designer Toys, Illustration, Ceramics, Artist Multiple, Slip Casting

Abstract

Collaboratively designed by students and faculty of the Illustration program at Emily Carr University, the Darwin project employs industrial ceramic processes but adopts the aesthetics and collaborative dynamics of the explosive “Urban Vinyl” subculture. As a generic figurative form that lacks detail and invites transformation through surface design, Darwin appropriates the strategy of the designer toy “platform”, popularized by Toy2R’s Qee and KidRobot’s Dunny. Unlike the vinyl toys that inspired them, the Darwin figures are conceived and presented primarily as a form of academic inquiry— an invitation to investigate our adaptive and/or conditional nature. Though the project employs a formal vocabulary derived from plastics and animation, a much older lineage of allegorical figuration is evoked by its translation into ceramic material.

Darwin celebrates the slippage between form, surface, and identity. In “A Vinyl Platform for Dissent: Designer Toys and Character Merchandising” (Journal of Visual Culture August 2010 vol. 9), author Marc Steinberg argues that the “Urban Vinyl” subculture represents a “site of resistance to the contemporary circulation of images and things”. This article argues that the field represents “a materially situated critique of the commercial practice of character merchandising,” stripping characters of their adherence to formula and branding, and the corporate entertainment franchising that governs that world.

Designer toys often traffick in absurd, pathological, and taboo subject matter, and it tackles its subjects in ways that can be socially insightful or just aggressively hedonistic. Often the figures are disruptive to dominant perceptions of propriety and decorum, but without positioning themselves clearly as either gratuitous irreverence or sly critique. In embracing this subculture within a University devoted to academic inquiry, our challenge is to generate work intuitively and impulsively while channeling the development of projects in ways that examine our collective production of images and consider its communal effect.

DARWIN / The Designer Toy Platform as a Means of Academic Inquiry

This paper concerns the inaugural project of an initiative at Emily Carr University of Art and Design called the Centre for Applied Art and Material Production (CAAMP).CAAMP is dedicated to cultural inquiry regarding the contemporary circulation of images and objects, with a mission to promote the integration of applied art practices with contemporary art culture. Driven largely (but not solely) by curricular projects, this Research Centre aims to facilitate the production of knowledge through collaborative design and manufacture. As an added challenge, it seeks to bridge incisive academic investigation with the mass appeal of collectibles, commodity culture, and the entertainment industry.

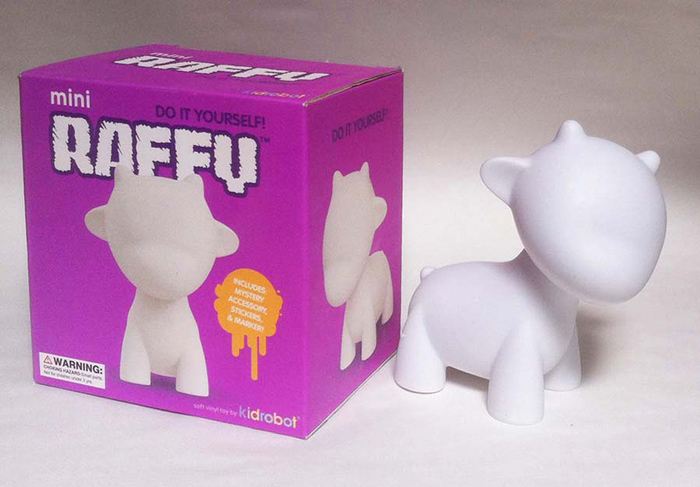

Figure 1: DARWIN a “Platform” for multiple surface designs

In this spirit, the “Designer Toy” industry serves as the framework for DARWIN, the subject of this paper and the first of CAAMP’s projects (See Figure 1). A full understanding of the project requires a bit of background on this industry and the subculture that supports it, as it is a territory that has grown explosively over the last 15 years and yet still maintains a niche of its own at the edge of mainstream. “Designer Toys”, or “Urban Vinyl”, or “Art Toys”, as they are variously labeled, are not the kind of products one typically finds at stores selling conventional toys for the entertainment or socialization of children. In this sense, the “Designer Toy” is not a toy at all, but rather a collectible intended for adults. It is created from the designs of an artist, a designer, or a collective, and most often mass-produced in modest numbers as a rotocast vinyl figure (though resins, fabrics and wood also have established a strong presence within the industry). Because they are born of artistic vision rather than massive production and merchandising, they are a category of object that clearly stands apart from other commercial toys. In fact, there has been a potent streak running through Designer Toys and Urban Vinyl– the tendency to combine the innocent and endearing proportions of traditional toy design with edgy or adult subject matter that conservative parents would consider inappropriate for children. The phenomenon of Designer Toys took shape in the late 1990s as practitioners within an array of creative industries and subcultures turned their attentions to subverting traditional toy design. Its pioneers hailed from established practices as diverse as apparel design, the music industry, street art, and illustration. As the movement continued to grow, so did its affiliations with other creative industries and subcultures.

From its earliest days, the Designer Toy and Urban Vinyl movement has possessed, at its core, a highly collaborative spirit. The Designer Toy “platform” quickly rose to a position of prominence within this emerging field. Popularized by Toy2R’s Qee and KidRobot’s Munny, among others, a “platform”consists of a generic figurative form that lacks detail and thereby invites customization through surface design. This strategy affords the company that produces the objects two key opportunities. It can enlist any number of artists and designers to provide surface designs for limited or unlimited production of various iterations of a singular popular form, and it can also sell “blanks”, or figures with featureless surfaces, that the general public can purchase and customize themselves (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Raffy, a Designer Toy “Platform” produced by Kid Robot

In “A Vinyl Platform for Dissent: Designer Toys and Character Merchandising” (Journal of Visual Culture August 2010 vol. 9), author Marc Steinberg argues that the “Urban Vinyl” subculture represents a “site of resistance to the contemporary circulation of images and things”. This article argues that the field represents “a materially situated critique of the commercial practice of character merchandising,” stripping characters of their adherence to formula and branding, and the corporate entertainment franchising that governs that world. It is in this sense that Steinberg deems “Designer Toys” to be truly disruptive, as they create and exploit gaps in normative cultural communication.

The Designer Toy “platform” represents the most aggressive challenge of all to the standardization of traditional character merchandising. By definition, all work created for a “platform” is collaborative in nature, and as Steinberg suggests, “runs counter to one of the basic tenets of character merchandising: the presumed singularity and uniqueness of a given character’s shape, color, and design.”

Figure 3: Dunnys from the Azteca II Series, byKid Robot

KidRobot is a company that has been particularly successful in this area, regularly commissioning new editions of a Designer Toy “platform” named Dunny, which are often released in a series that combines the work of various artists. One Dunny series of note is the Azteca II Series, introduced in 2011, which brought the work of Mexican artists together with that of Chicano artists living in the United States in order to explore a common heritage across the border that separates them (See Figure 3). Other Dunny series have gathered artists that share common experience, thematic interests, or nationality, but the Azteca II Series represented a particularly fascinating exercise, beyond the inherent subversion that fascinated Steinberg. A broad range of iconography was explored by the Azteca II artists, and the series was given a uniquely provocative edge by the manner in which some artists opted to appropriate clichés or negative stereotypes of Mexican identity.

The Azteca II Series reveals the potential of the Designer Toy “platform” to investigate how the collective and potentially disparate concerns of a certain constituency might be manifested symbolically or allegorically. A series of such figures could in fact be considered a research tool, to be applied to complex questions that might be better understood if addressed in a plurality of interpretations. An academic project could employ these means to explore the ability of a collection of objects to communicate through their interrelation; a collection that shares a certain kinship in its point of departure, but might offer poignancy in its divergence; a collection that does not strive for clarity or fixed meaning, but rather offers the fragmented view of a prism. In this multiplicity of representation, we might continuously revisit the complexities of a given question.

~

Collaboratively designed by students and faculty of the Illustration program at Emily Carr University, the DARWIN project is a response to that challenge. It employs ceramic processes but adopts the aesthetics and collaborative dynamics of the Designer Toy “platform”. As a generic figurative form that lacks detail and invites transformation through surface design, DARWIN celebrates the slippage between form, surface, and identity that Steinberg addresses, and chooses as its theme the examination of our own transformative nature.

Though it functions unapologetically as a commercial product, each figure represents an invitation for a surface designer to investigate the adaptive nature of our existence. It offers the potential to tackle questions of identity and the manner in which our environment shapes it; questions that drove the work of Charles Darwin. In homage to the project’s namesake, artists submitting surface designs are asked to address how their iteration in some way reflects our responsive, transformative, and/or conditional nature.

The DARWIN project strives to build upon and expand the function of inquiry that is often latent in the Designer Toy. Cultural inquiry is here placed in the driver’s seat, so to speak, as part of University curriculum, and the objects are conceived and presented primarily as academic investigation. Taking inspiration from the Dunny’s Azteca II Series in particular, the DARWIN project is an experiment that explores the mutability of cultural identity through the modification of a mutable object.

Designer toys are products that regularly traffick in absurd, pathological, and taboo subject matter, and they frequently tackle their subjects in ways that can be socially insightful or just aggressively hedonistic. Often the figures are disruptive to dominant perceptions of propriety and decorum, but without positioning themselves clearly as either gratuitous irreverence or sly critique. In embracing this subculture within a University devoted to academic inquiry, our challenge is to generate work just as intuitively and impulsively, but to channel the development of those projects in ways that examine our collective production of images and consider its communal effect.

~

This experiment was conducted within the framework of a relatively young Illustration curriculum at Emily Carr University. This curricular area was introduced in 2009 as a new stream of study within a Visual Art degree program (recently reconstituted as the Audain School of Visual Art) that has been firmly rooted in the practice and culture of Contemporary Art, and its relationship to the larger program is still evolving. Because of a longstanding curricular emphasis that subjects mainstream mass-culture to rigorous (and often relentless) cultural critique, Illustration students aiming to develop work for commercial markets must negotiate a set of objectives that can appear to be operating at cross-purposes. Contemporary design culture may have largely evolved beyond approaches that emphasize “solutions” to “design problems” within fixed systems (to now prioritize the questioning of the larger systems themselves), the older paradigm continues to dominate many client-driven practices. That legacy can also appear to be at odds with the core priorities of Contemporary Art culture, which prizes the ability to problematize or to raise questions over the formulation of quick solutions.

This challenge is certainly not unique to Emily Carr University, as many institutions of higher education encompass both commercial and fine art, and must reconcile the distinct pragmatic considerations, audiences, and objectives of the two. In his essay “Expanding Illustration Design Studio Practice through Critical Reflection”, David Blaiklock articulately breaks down some of the tensions around criticality within the study of illustration, as he addresses specific pedagogical strategies implemented at the University of South Australia in Adelaide.He advocates increased critical reflection that serves to “question assumptions” beyond the customary prioritization of “judgments about the project outcome, design processes, visual techniques and production processes”. Citing a wide array of thinkers on the subject, Blaiklock affirms the impressive degree of technical and dialogic reflection that underpins the practice of illustration, while noting the need to deepen the kind of reflexivity that questions the cultural or socio-political presumptions that might be endemic to mainstream media or markets– presumptions that might be overlooked within the industry itself. Indeed, it is often the fact that a professional illustrator is not in a position to challenge the underlying ethics of a client’s product that undercuts the deeper examination (and suspicion) of implicit suggestions within images or narratives in a commercial context.

The framework of Designer Toys has unique value in regard to exercising criticality within illustrative practices. Though it would be a gross generalization to characterize any facet of Illustration practice as being uniform in style or content, many professional applications do have distinct tendencies or favored methodologies. “Editorial Illustration” is an area of practice that exhibits kinship with conceptual approaches prevalent in the Contemporary Art sphere, often celebrating images that remain open or even paradoxical in their meaning. In this regard, Editorial Illustration dovetails more easily with objectives common to Contemporary Art culture. Because these illustrations often aim to reflect the subtleties of debate, or serve to highlight contentious issues in politics or current affairs, they will ideally resist comfortable resolution in the mind of the viewer. A concise visual metaphor might be the Art Director’s goal, but typically it is a graphic means to capture unresolved tension.

The entertainment industry, on the other hand, is rife with images and narratives that ultimately deliver neat resolution, regardless of whether they defy expectations en route, or question prevailing values. The territory of Designer Toys holds exceptional promise in that it is highly commercialized and unrepentantly indulgent in its embrace of sheer entertainment and marketing, and yet its content is as slippery and ambiguous as Editorial Illustration—and often more so! This is evidenced in the frequent use of mashups in Designer Toys, which arrive at novel creations by casting familiar mass-culture references into new and entirely absurd contexts. Though these might originate as purely impulsive gestures, they occasionally deliver the unnerving disruption of a surrealist Exquisite Corpse, or result in insightful social critique.

It is incumbent upon academic programs specializing in Illustration and Animation, particularly here on North America’s West Coast, to both engage and question the role of entertainment industries. Designer toys offer an ideal laboratory for experimentation because they occupy a marginal space where corporate-controlled mass-entertainment and mass-market consumer goods are typically engaged outside of the logic or purpose that typically governs those territories.

~

The fact that this genre of object straddles the divide between art and design offers further pedagogical value. In his essay “Vinyl Rules: Surrogate Sculptures and the Manufacture of Identity”, Carlo McCormick asserts that the Designer Toy hews to the lineage of the “Artist Multiple” as much as (or more than) that of the toy. “(B)y lineage and legacy this is actually the kind of subgenre that belongs to the species of artists’ multiples,” offers McCormick, as he draws a thread from contemporary vinyl toy designers back to luminary artists such as Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Beuys. In the vinyl industry, editions can be small in number or quite large, and individual objects can vary in scale from pocket-sized products sold in “Blind boxes” to large “One-off” sculptures. This allows for a complex culture simultaneously operating within diverse economies, catering to audiences that include both casual shoppers and specialized collectors.

In addition to its connection to the “Artist Multiple”, there are deeper historical traces that are perhaps still more intriguing. The DARWIN experiment harnesses the formal vocabularies and themes that are typical of vinyl Designer Toys and translates them into ceramic materials. One could argue that the success of “Urban Vinyl” lies largely in the tensions created by the uneasy integration of the child-like playfulness of the toy and the anarchic, streetwise, or surreal subject matter. If so, the layering of yet another symbolically charged element—that of the ceramic figurine and its historical and material connotations—offers the opportunity to explore dynamics of even richer cultural complexity.

Although resin, “plushies” made from fabrics, and even wood have all grown in popularity, traditional ceramics remains relatively under-explored in the field of “Designer Toys”. When the time-honored medium of ceramics adopts a formal vocabulary that is typically associated with plastics and animation, it can acquire an uncommon resonance. As contemporary as the surface design might be, each DARWIN figure possesses an undercurrent of vulnerability and nostalgia that is manifested in ceramic material itself.

~

In Society of the Spectacle, the French theorist and cultural critic Guy Debord writes: “(C)onsciousness of Desire and desire for consciousness are the same project”. More than a clever turn of a phrase, the statement asserts that higher knowledge will come from reckoning with our deepest impulses, however base they may seem, not by safely rising above them. Those of us who teach in the arts at academic institutions would be wise to take heed. Debord’s words suggest a methodology wherein commercial practices for mass audiences fully embrace deepened critical reflexivity and poetic inquiry. In this vision, distinctions between Contemporary Art practices and applied commercial practices might even begin to seem inconsequential.The quote succinctly captures the spirit with which the DARWIN project was undertaken, and I believe it can serve as a guiding light for any who aspire to a comprehensive engagement of visual culture, high and low.

Individual DARWIN Designs

Figure 4: DARWIN Surface Design by M.J. Hur, 2011

Min Joo (M.J.) Hur was a member of the team that collaboratively designed the original form—the “platform” itself. One of Hur’s DARWIN surface designs playfully merges the architecture of the Church with contemporary anthropomorphic character design (See Figure 4). Class, taste and status are challenged in the resulting mashup by placing the two on level ground. The incongruity upsets the narratives and rhetoric typically associated with both animal fables and institutionalized religion. Given the project’s context of Darwinian questions, there is perhaps also an implicit nod to the longstanding friction between scripture and evolutionary science.

Figure 5: DARWIN Surface Design by Nomi Chi, 2012

Nomi Chi participated in another advanced illustration class at Emily Carr University in the Fall of 2012 in which she created a DARWIN surface design that was inspired by the artist’s experiences in Japan (See Figure 5). Impressed with the manner in which issues both great and small are addressed to the Nation’s public via cuteness and hyperbole, she employs similar tactics in her attempt to channel growing anxieties over the ocean and the scale of its potential for environmental disaster. Fukushima’s radioactive seawater, the melting of polar ice caps, growing acidity and shrinking fish stocks are all imminent dangers that might be conjured up by her surreal imagery.

Figure 6: DARWIN Surface Design by Amelia Butcher, 2012

In the Spring of 2012, CAAMP announced a call for submissions of additional surface designs for DARWIN (an event that CAAMP intends to periodically restage). The Grand Prize, which consisted of CAAMP’s production of an edition of six 12-inch figures featuring the winning design, was awarded to Amelia Butcher. Butcher’s design aims to reclaim the stereotype of the witch (See Figure 6). Once burned at the stake, the witch featured on this DARWIN now lights her own fires at will, and delights in the kind of ambiguous identity that can challenge patriarchal establishments.

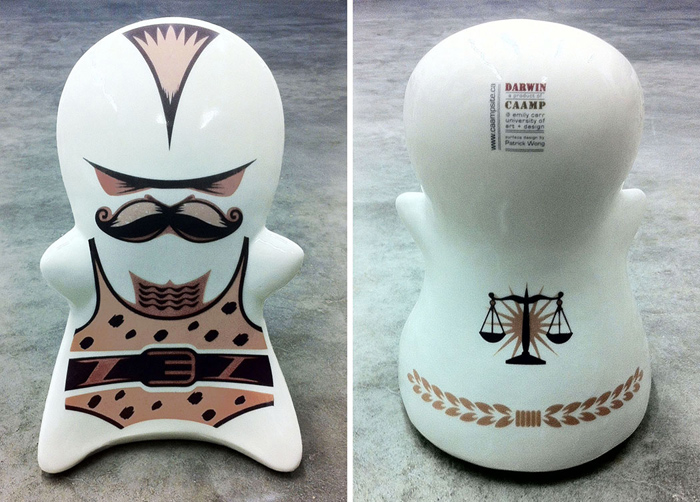

Figure 7: DARWIN Surface Design by Patrick Wong, 2012

In the same competition, Patrick Wong’s design was also awarded a prize. His DARWIN is inspired by an essay titled “The Ring”, in which French theorist Roland Barthes proposed that wrestling in 19th century France was a spectacle that reflected complex notions of public justice. Wong’s DARWIN bridges high and low culture, reminding us that the entertainment we consume is laden with deeper subtexts (See Figure 7).

Figure 8: DARWIN Surface Design by Michael Salter, 2013

The first artist unaffiliated with Emily Carr University to be invited to submit a design for the project was Michael Salter. Salter serves up a DARWIN covered with icons he has developed over the years on the theme of animals (See Figure 8). Loaded with psychic dissonance, his reductive graphic approach suggests banal and trivial commercial signage, but instead offers dark and irrational glimpses of inter-species tension, including predation, extinction, anthropomorphism, adaptation and mutation.

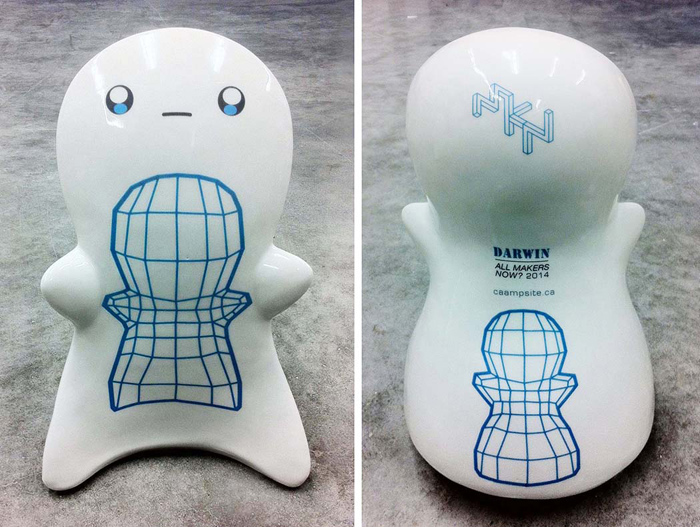

Figure 9: DARWIN Surface Design by Philip Robbins and Justin Novak, 2014

Philip Robbins and Justin Novak (the author of this paper) collaborated on a DARWIN surface design that commemorated their participation in the conference “All Makers Now?”, which took place at Falmouth University (UK) in July 2014. An earlier iteration of this paper was presented at that conference, which examined a host of challenges and opportunities facing those invested in both handcraft and digital technologies. This self-referential version offers a DARWIN that is emblazoned with a digital wireframe version of itself, reflecting the migration of our identities into the virtual realm. A playfully existential iteration, it hints at the conference’s overarching concern– the reconciliation of virtual and material manifestation– and invites consideration of a broad set of attendant questions around authenticity, value and accessibility.

Bibliographic References

Steinberg, Marc “A Vinyl Platform for Dissent: Designer Toys and Character Merchandising” (Journal of Visual Culture August 2010 vol. 9)

David Blaiklock, “Expanding Illustration Design Studio Practice through Critical Reflection”, Conference Paper, presented at DesignEd Asia, Hong Kong, 2011

McCormick, Carlo, “Vinyl Rules: Surrogate Sculptures and the Manufacture of Identity”, published in “Full Vinyl: The Subversive Art of Vinyl Toys” edited by Ivan Vartanian, Published by Collins Design, New York, in 2006

Debord, Guy, La Société du Spectacle(Society of the Spectacle), 1967 Buchet-Chastel (Original French); Zone Books (English Translation)

Addendum:

The DARWIN platform was collaboratively conceived in the Fall of 2011 by a creative team that consisted of an advanced Illustration class at Emily Carr University, its instructor and a teaching assistant. The group was comprised of Brad Allen, Dianne Almond, Hae Jin An, Cathleen Chow, Hyun Chung, Min Joo (M.J.) Hur, Mark Illing, Ainsley Jasper, Pierce Jordan, Soo Min Lee, Nicole Majcher, April Milne, Jieun Min, Justin Novak, Joanne Oh, Sterling Richter, Jen Uy, Alison Vogelaar, and Emma Walter. (Fellow CAAMP Researcher Philip Robbins was instrumental in the digital protoyping and of the form, which further refined the design)

Justin Novak

Director, Centre for Applied Art and Material Production (CAAMP)

Associate Professor, Faculty of Visual Art + Material Practice

Emily Carr University of Art + Design, Vancouver BC V6H 3R9 / [email protected]

Website: www.campsite.ca

Back to News Page