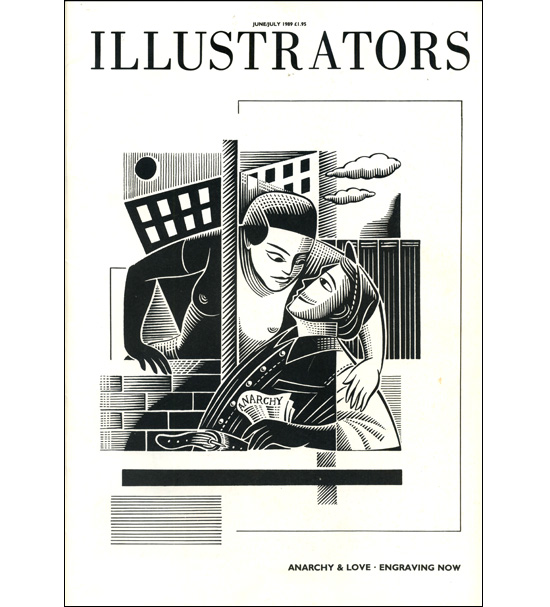

Illustrators – The Anarchy & Love Issue 1989 – archive

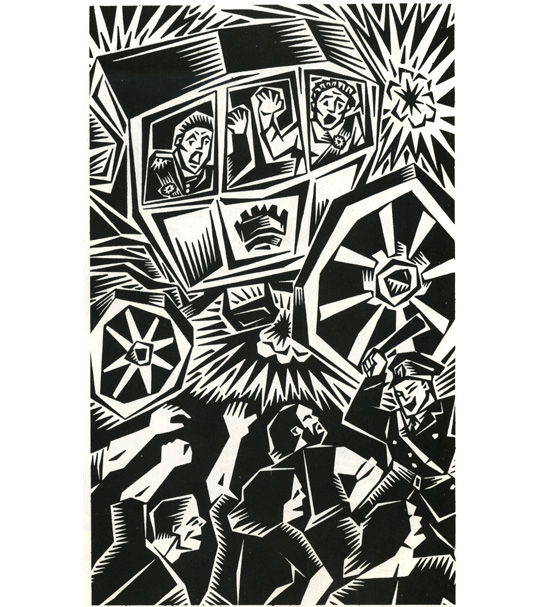

Clifford Harper for Anarchismo, an Italian anarchist journal

As we continue to look through the archive of the AOI membership publications, we discover a copy of Illustrators magazine from the summer of 1989. Issue 68 – The Anarchy & Love Issue features in depth articles on engraving, discussing the tools of the trade and the subject matter of several wood engravers. The issue also explores the politics of illustration.

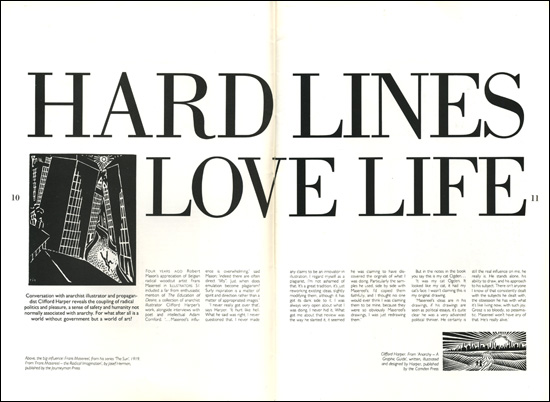

Left: Frans Masareel from his series The Sun, 1919. From Frans Masareel – the Radical Imagination by Josef Herman, published by the Journeyman Press. Right: Clifford Harper from Anarchy – A Graphic Guide published by Camden Press

In Hard Lines Love Life the anarchist illustrator and propagandist Clifford Harper discusses his influences and the process and drive behind his practice. He reveals the coupling of radical politics and pleasure in his work, and explains how his woodcut-mimicking pen drawings have changed over the years.

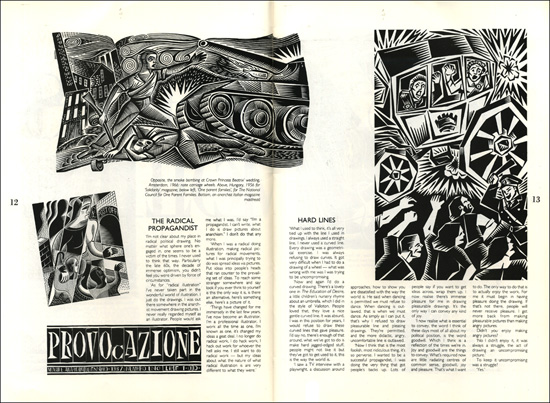

Clockwise from bottom left: an anarchist Italian magazine masthead, One Parent Families for The National Council for One Parent Families. Hungary 1965 for Solidarity Magazine, the smoke bombing at Crown Princess Beatrix’s Wedding, Amsterdam 1966. All by Clifford Harper

“I was out there somewhere in the anarchist movement drawing pictures. I never really regarded myself as an illustrator. People would ask me what I was, I’d say “I’m a propagandist. I can’t write, what I do is draw pictures about anarchism.” I don’t do that anymore.

When I was a radical doing illustration, making radical pictures for radical movements, what I was principally trying to do was spread ideas via pictures. Put ideas into people’s heads that ran counter to the prevailing set of ideas. To reach some stranger somewhere and say look if you ever think to yourself is this the only way it is, is there an alternative, here’s something else, here’s a picture of it.”

“What I used to think, it’s all very tied up with the line I used in drawings. I always used a straight line, I never used a curved line. Every drawing was a geometrical exercise. I was always refusing to draw curves. It got very difficult when I had to do a drawing of a wheel – what was wrong with me was I was trying to be so uncompromising. […] I was in this position for years, I would refuse to draw these curved lines that gave pleasure. I’d say no, there’s enough of that around, what we’ve got to do is make hard jagged-edged stuff, people might not like it but they’ve got to get used to it, this is the way the world is.”

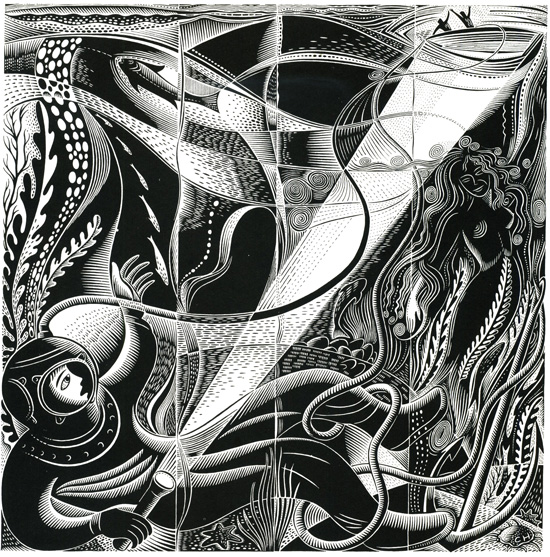

Deep Water for Trickett & Webb’s 1989 calendar

“The woodcut look with a Rapidograph pen… I like everything about it. There’s immense discipline required, and I like that; there are such problems to overcome with black and white line. To achieve light and shade without any tonal work is such a challenge. Illustration is always a problem to be solved. I like getting to grips with the real limitations of black and white. I’m not interested in solving things easily with tone work. Really what I like about it is the dynamic.

The pen is the result of an accident. I’m self taught, and the first pen I picked up was a Rapidograph. I got stuck with it. It’s the worst pen imaginable for doing what I do, The whole way I draw is the most ludicrous thing imaginable, trying to draw cuts with a Rapidograph. I should stop working, go to art school, learn to cut wood and come back. I don’t even try to use a fluid open pen. You can’t do a fluid curve with a Rapidograph, you can’t do anything. […] The only principal point to be made is the human condition, really. We’re all stuck with limitations. In the past I was very politically convinced about this. I wasn’t going to put my pen aside and learn to do it properly because why should I make myself different from everybody else? If everybody struggles under absurd limitations in every sphere, why should I be anything different?”

Back to News Page