Graham Rawle

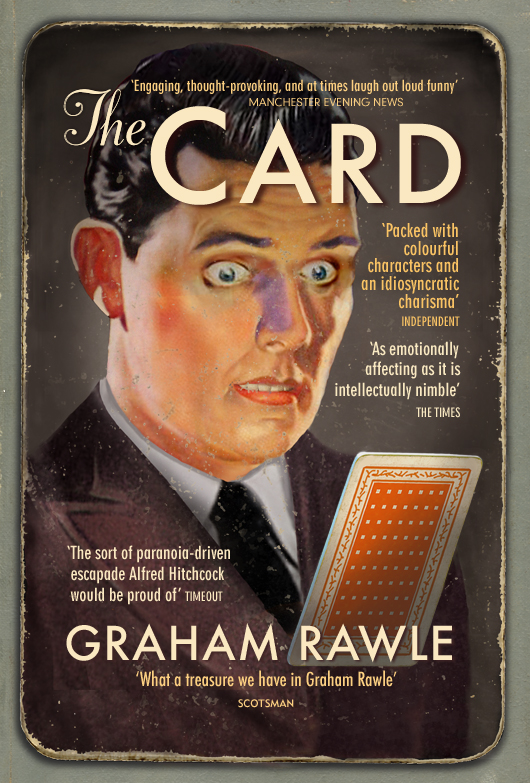

The Card – paperback cover

When did you realise you wanted to make creativity part of your career?

As a kid I was always writing stories, making scrapbooks and magazines, building collections (bubble-gum cards, matchbox labels, toy soldiers etc.), making up jokes, drawing pictures. None of this seemed like work to me and I never imagined that I’d later be allowed to do these things as a job. Now, fifty years later, I think it’s quite funny that I’m doing more or less the same as I did back then and that this is now called ‘my career’. I am highly motivated when I’m involved in my own projects, but otherwise I can be quite lazy. My projects don’t always make a lot of money, but that isn’t important to me. If you’re committed to only doing the work that you really want to do, you have to be prepared to make sacrifices in other areas.

What was your first big break?

Back when I was doing illustration in the ‘80s I came up with an idea, ‘Lost Consonants’, which I thought could run as a series: my own little weekly slot in the newspaper. At the time I was regularly doing editorial illustrations for the Weekend Guardian so I approached the editor, Roger Alton, who agreed to do six of them to see how they went. After the sixth one appeared, I hadn’t heard anything, and I wasn’t sure anyone at the paper was counting, so I cheekily sent in a seventh. It appeared, and I got paid for it, so the next week I sent in an eighth. Still no one said anything so I just kept on sending them in. I did this for the next 15 years. Editors came and went; I don’t think I ever spoke to any of them. The series ran from 1990 to 2005.

This weekly presence opened a doorway into publishing. The Lost Consonants books I’d produced sold quite well and this led to publishers Victor Gollancz inviting me to create my own book. I came up with a strange puzzle and games book, The Wonder Book of Fun, and this subsequently led to other published books. Lost Consonants also enabled me to take more control of my work. I gradually stopped doing commissioned illustration work in favour of initiating my own projects.

Lost Consonants – series from The Guardian

Words are an influential on your practice, how do you work illustration and text together?

I’m interested in the interplay between text and image, how one can be made to affect the other, and what lies in the gap between them. My books experiment with this idea of a narrative subtext that is neither written nor illustrated but emerges through the combined reading of both text and image to form a new language.

‘Do the cha cha cha’ – Illustration from The Card

You have created novels such as The Card and Woman’s World, describe your process as an illustrator?

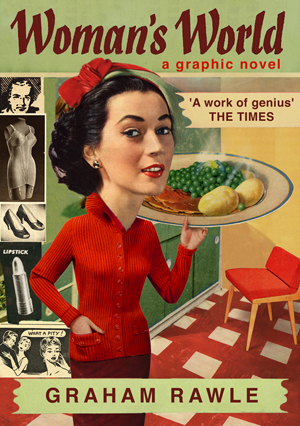

The process changes according to the project. It can involve writing, installation, photography, model making, drawing, book design. That said, there are certain commonalities. I often work in collage, I enjoy the constraints. Having to make do with what is available forces me to be more inventive and I like how the found elements bring with them the flavour of their original context. My work is usually set in and around my childhood – the 1950s and ‘60s – so this works well to create the right feel for the themes I want to explore. In my book The Card, the ‘found’ cards are actually all created by me to (hopefully) look like bubble gum, cigarette and game cards that might have been around in the past. Although there are a few little spot illustrations in Woman’s World the real illustration is the text itself, which, because of the process, also becomes image, a visual representation of the protagonist and her story.

Woman’s World – Paperback cover

What appeals to you about the audience participating in your work, such as within Pardon Mrs Arden?

Audience participation is very important. A lot of my work, like ‘Pardon Mrs Arden’ and ‘Lost Consonants’, uses humor that requires the audience to connect the dots to make the joke work. The motto is ‘Don’t give them four, give them two plus two and make them do the adding up’. It’s more rewarding if they are made to engage with the idea. Screenwriter Andrew Stanton calls it the well-organised absence of information. It makes good storytelling. The joke is a very simple form of this, but I use these principles in my novels. My writing has, I think, quite a cinematic feel because my understanding of story comes more from cinema than from literature. In my books there are lots of gaps that the reader is required to bridge to make the narrative connections. It works like the Kuleshov effect does in film editing. I am currently exploring these ideas further in a film version of Woman’s World, which will be collaged together using only found footage clips.

You have made books, created editorial pieces and made props, how important do you think a varied way of working is for your practice?

I’m quite happy to switch working methods, to let the content of an idea determine how the work should be delivered, but I don’t embark on some new working method just for the sake of it. Some ideas work better as images, some as words, some as moving image, theatre, sound, installation etc. You have to choose the right medium to maximize the effectiveness of your message.

You collaged together words found in 1960’s magazines to make Woman’s World. How long did it take you to piece together a narrative? How did you go about planning this?

I had been writing a story about a housebound and somewhat troubled woman, Norma, whose life is governed by the ideals prescribed by the women’s magazines she reads. The shortfall leads her to create a persona entirely fabricated from the words in the magazines. When it occurred to me that Norma was actually a cross-dressing man, the whole thing made perfect sense. Women’s weeklies from that period actually read like a ‘how to’ instructional manual for the budding transvestite – everything you need to know to achieve perfection in all areas of womanliness.

I spent five years creating Woman’s World, piecing together 40,000 fragments of text. The process was quite complicated and incredibly labour intensive.

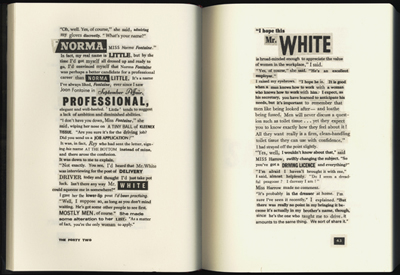

After some experiments letting the found text determine the direction of the narrative, I decided to write the novel as a normal word document. At the same time I gathered and archived any fragments of magazine text that I thought might be useful. I transcribed all of this stuff to form a kind of word/phrase bank that could be word-searched, each typed piece carrying with it a scrapbook volume and page number to identify where the actual text piece was stored. Still working in Word, little by little I replaced all of my original manuscript with the found text, creating an approximation of my original writing, but now the new words carried with them the voice of the original women’s magazines. Norma’s voice. Once the story had been through several edits I was finally able to paste up the 437 page story as artwork.

Having established the look of the narrative voice, I needed to ensure as comfortable a reading experience as possible. I designed a simple formal type grid, which runs throughout the book. I occasionally break through its parameters in order to visually underscore the dramatic tension in a particular scene. I believe that the book design, the layout of the page, must be governed by the content. Any design elements or textual anomalies must add something to the story, not detract from it.

Woman’s World – page spread

Back to News Page