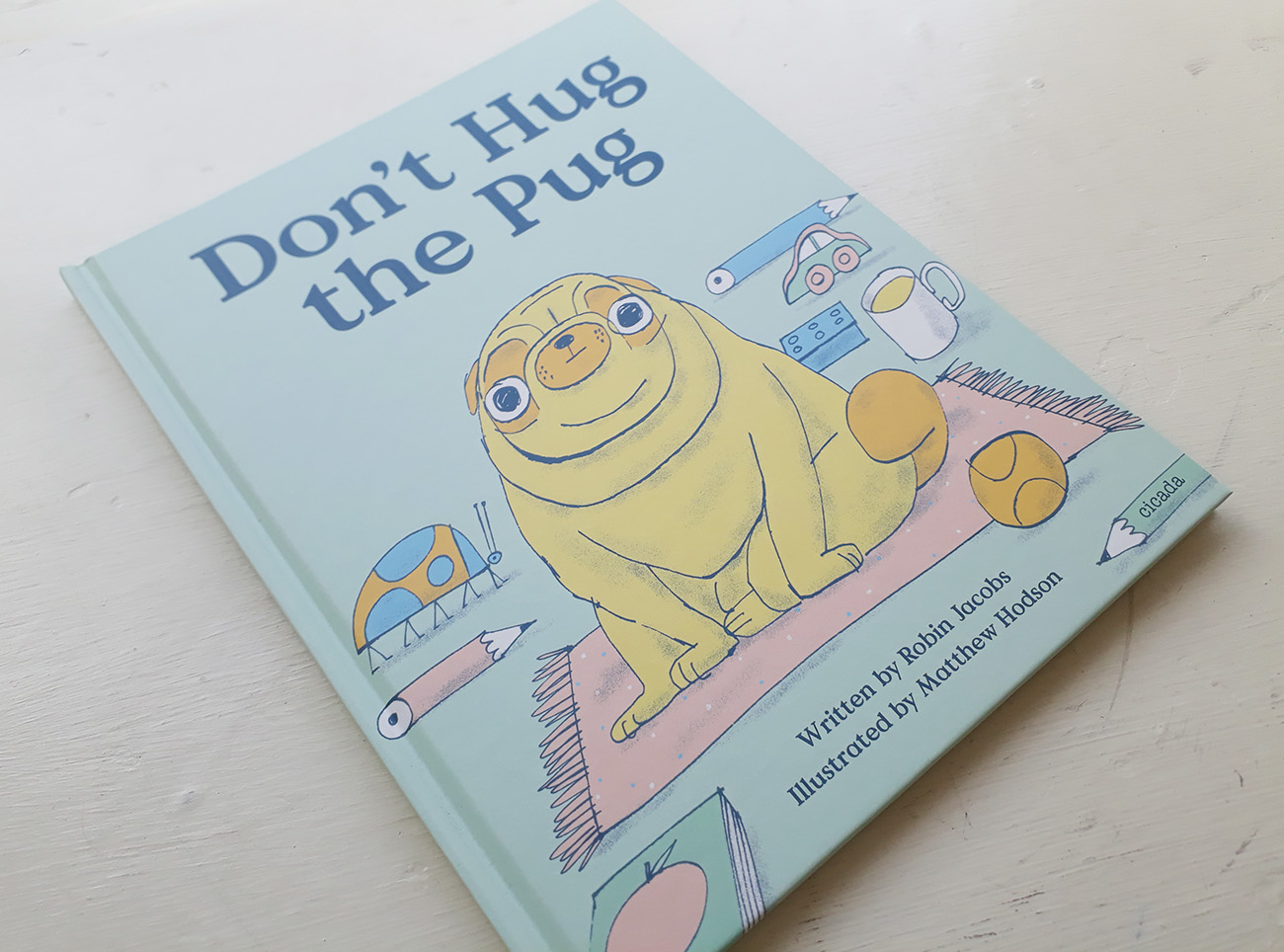

Don’t Hug The Pug – Book Review + Interview

Written by Robin Jacobs illustrated by Matthew Hodson

Published by Cicada Books

Review by Peter Allen

Don’t Hug The Pug is a story about a dad, toddler and pet dog, a pug, playing a happy rhyming game together. Written by Robin Jacobs, the story was illustrated by Matthew Hodson not long after the birth of his own baby boy, a happy coincidence that would directly inform his work, rendering his pictures so enjoyably observant and anecdotal.

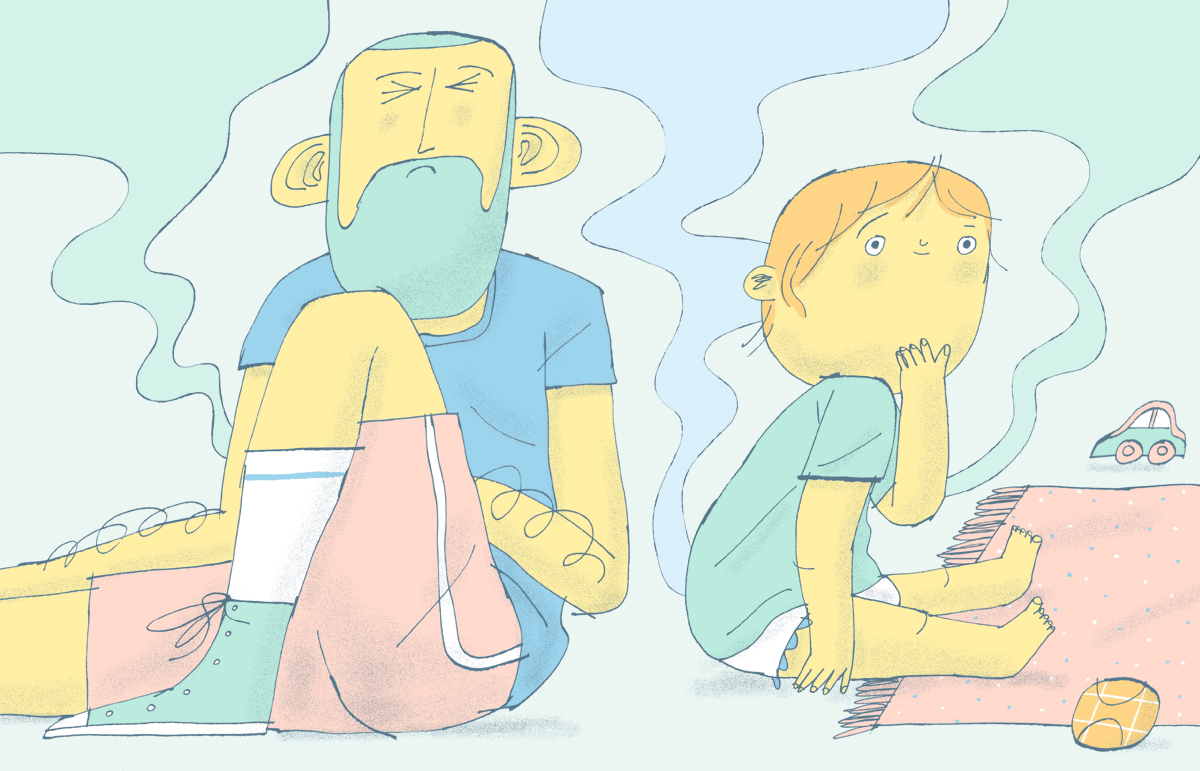

The book celebrates those moments before baby is up and about, when parent and baby spend time playing, as here, with the sounds that form words, seeing them afresh, inventing new associations and possibilities. In a less wacky, Dr Zeuss sort of way the game involving a jug, bug and rug, becoming a fun lesson about not hugging pugs – or so it would at first appear. Starting the book I did think that the story’s punchline was going to be delivered differently, more directly, so was delighted by the surprise ‘double dream’ ending.

For Matthew the story “felt very different from the my own stories, which appealed a lot as an image maker. Having recently had a baby boy at the time, the content felt very familiar so I agreed to take on the work… the dynamic between the father and son grew each day as I became more and more familiar with the characters. I used photos of myself playing with my son on the carpet and studied the way parents have to get down the the child’s level all the time and how to capture this…” His varied practise as illustrator, poet and lecturer has deepened his appreciation of “the interplay between writing and illustration… being a parent now, I have become obsessed with the world of children’s picture books. What an amazing vehicle for ideas and pictures and what an incredible audience”.

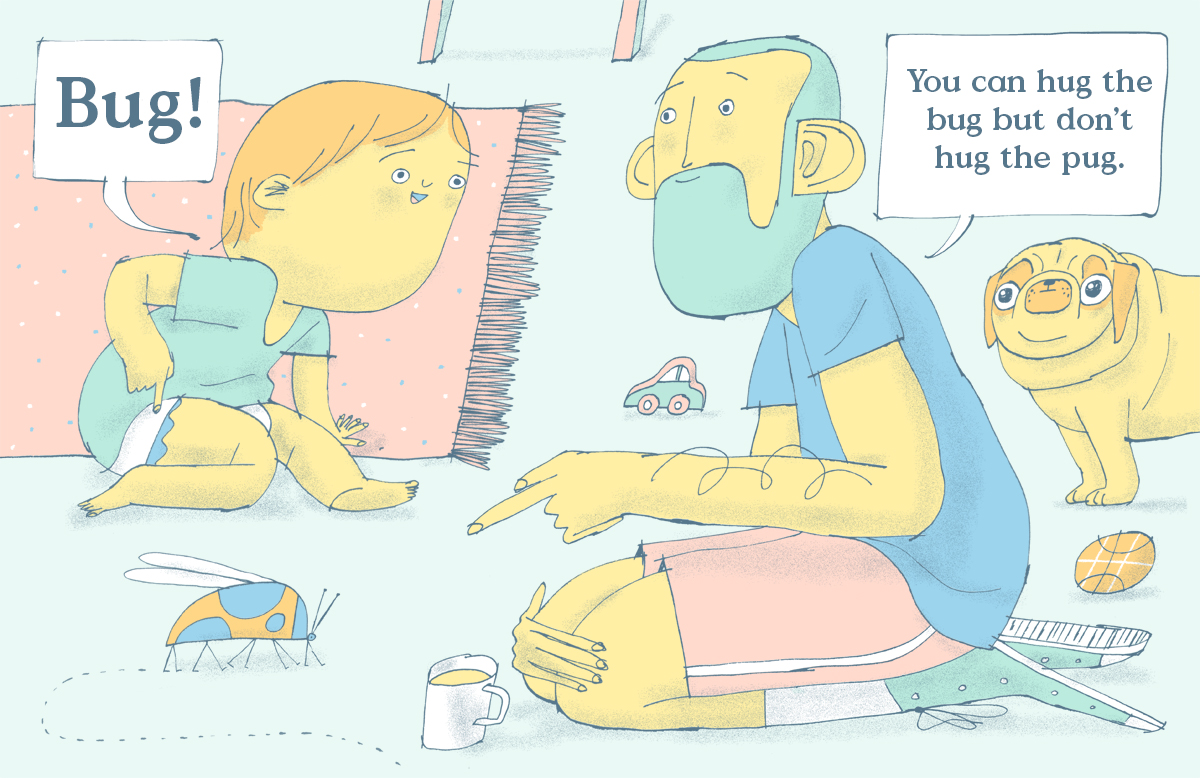

Matthew matches his graphic style to the simplicity of the the text, to the familiar shapes and sounds described to its young audience. His pictures are presented like a series of stageset-like spreads, which can be read out loud like samplers, as expanding inventories that encompass the landmarks of the baby’s known world; Lego, board book, baby wipes, toy car, ball, crayons… The flattened picture space centres on the focus between the parent and child, bringing the present to the fore, forgetting about everything that is beyond.

The fleeting nature of the moment, the urgency with which babies grow and change already infuses the images with a certain sense of nostalgia, the sweet sorrow, reflected by the muted palette of colours. Meanwhile, the pen-drawn line remains cheerfully unaffected, full of beans. “I like lines that speak with a hopeful wonk, a robustness and a mischief”. It outlines a more simplistic view of things that could be the baby’s or a more idealistic take as seen by the parent. Whatever, the line’s untiring energy comes, most likely, from the baby’s gaze; spotting a toy there, a bug there, dad’s hairy legs, laughing at the pug’s face, a constant source of curiosity and amusement. Stripped of unnecessary detail the pictures convey all the fondness of a happy memory like a sleeper waking from a night’s dream, only to find that it’s not quite over yet…

Don’t Hug The Pug is just the book for parents and kids to enjoy at an age when playing games is still an essential part of learning, where sitting on the rug with baby and pug (and bug…) is visibly the heart of the matter. It is a place that Matthew seems in no hurry to leave, “being a parent now, I have become obsessed with the world of children’s picture books, what an amazing vehicle for ideas and pictures and what an incredible audience.”

Peter asked Matthew more questions on the project:

Could you describe briefly how you came about to do what you are doing now?

I’m fascinated by the craft of making pictures, telling stories, sharing ideas and engaging with others. I think my earlier interests sat more in a performing arts context, but art school seduced me, as did print making, then graphic design, then alt-comics, then illustration, then whatever came after that.

I’ve tried my best to maintain some sort of involvement in the all of above through various means for the past decade. It’s not always been easy and at times other things have had to take prescient, but I have always tried to maintain some sort of creative activity for its own sake and I think that has been of huge value.

How would you describe who you are and what you do?

Primarily, I’m an illustrator but I also maintain a practice in poetry and print making. I’m also a lecturer at Leeds Arts University on the Illustration degree. I ricochet between client work, personal work, creative writing, academic writing, teaching, planning, drawing, playing, trying and lying down.

How did DHTP come about?

I was approached by Cicada with a manuscript for the story. It felt very different from the my own stories, which appealed a lot as an image maker. Having recently had a baby boy at the time, the content felt very familiar, so I agreed to take on the work.

Did you know what you wanted to achieve visually when you started work on this project or did the idea evolve during the making of the book?

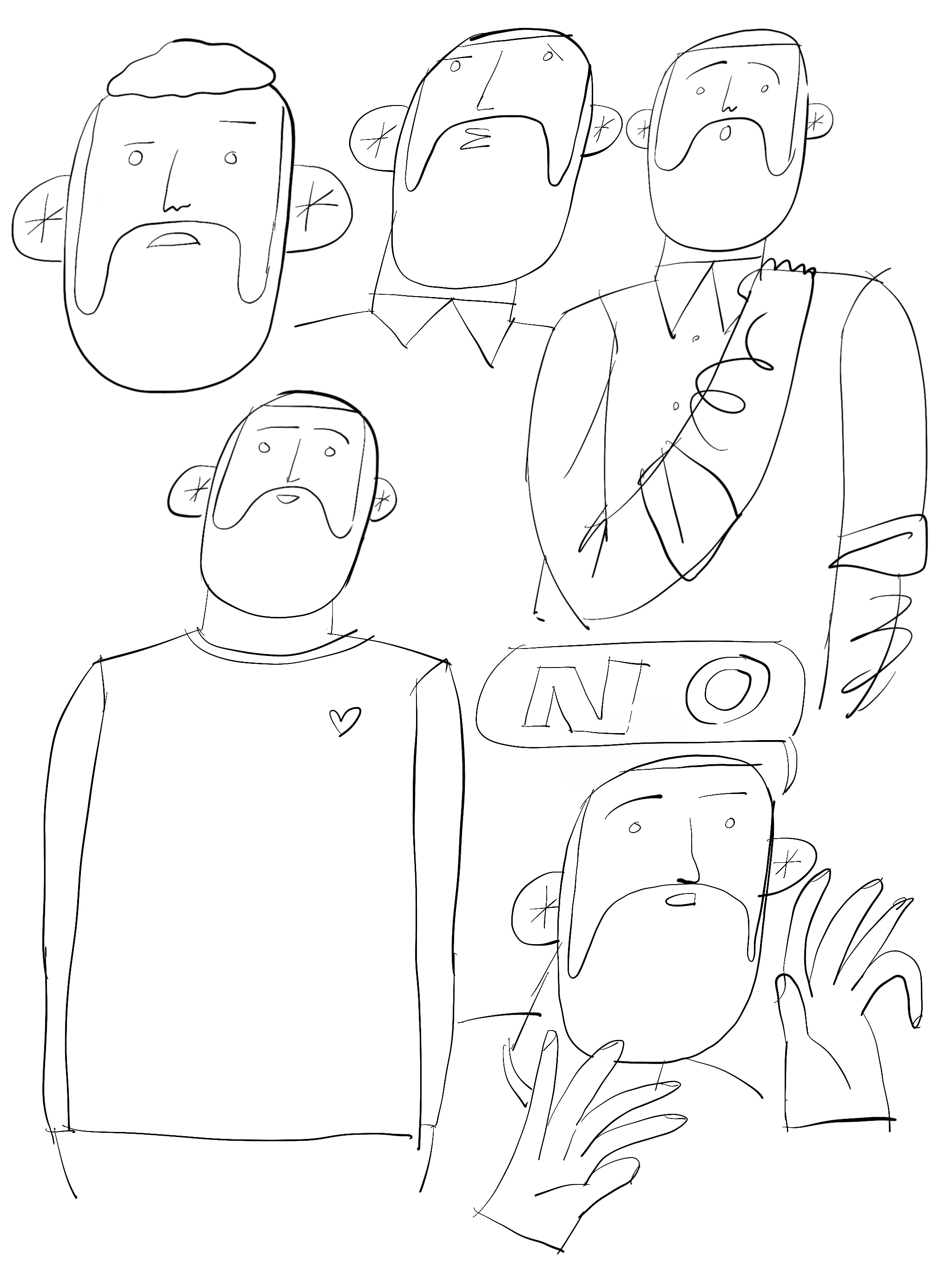

I had very little idea really, we agreed that the pug needed to be a bit wonky and daft, but the dynamic between the father and son grew each day as I became more and more familiar with the characters. I used photos of myself playing with my son on the carpet and studied the way parents have to get down the the child’s level all the time and how to capture this through figure.

What influences, interests are particularly relevant to your work and the way we look at, understand and appreciate it?

Well I’m at a bit of a cross roads to be honest, I’m currently trying to evolve my practice and have been doing a lot of experimentation to figure out what this is and what it could be. Though limiting in many ways, I’m still in love with the drawn line and so I think I’m going to keep on drawing lines, but how does one draw a line? I like lines that speak with a hopeful wonk, a robustness and a mischief. I like gestural lines, and ugly lines, with little hats on. I like the way that great lines are honest and familiar and trustworthy and caring. I like lines that are assured and have purpose, even whilst getting lost.

I have an airbrush compressor and some new charcoal, anything is possible.

Could you describe something about the processes involved in the making of the artwork?

We did early rounds of character sketches, then test scenarios. After that there was a full story board plotted out with notes and amends. After that we went one spread at a time with additional notes and changes to plot and pacing as the tone of the collective pages emerged. I remember redesigning the child’s face some way through, to help achieve more character so I had to go back and edit previous drawings. It was a new experience for me – consistency really is necessary with such a simple plot so I needed to try get the basics right.

Did this project represent for you a new way of thinking, making, expressing ideas…?

Yes, absolutely. I self published my own book of poetry a few years ago and it ended up being my favourite project to date. I really relish the interplay between writing and illustration so that’s my goal moving forward. I’m writing and making and we’ll see where it goes. Of course, being a parent now, I have become obsessed with the world of children’s picture books – what an amazing vehicle for ideas and pictures, and what an incredible audience.

Ideally, what project would you like to work on next?

DHTP was a good learning curve in regard to process and format. But I’d like future book work to feel different, perhaps more weird (and familiar). More mess and less pugs. I want to make kids books that feel inclusive and approachable, but somehow carry a tone of irreverence and mischief that resonates in the gutter.

How do you view book publishing at the moment, commercial and independent, does it support and/or encourage enough original or unusual projects to see the light of day?

Cicada were an absolute pleasure to work with, I’m aware they’re a small outfit and that allows them to offer more flexibility and artist input I suppose, though I’m not talking with a great wealth of experience. I’ve had other projects not get past acquisition with other publishers but always on reasonable grounds. Half an idea or an idea with potential isn’t the same as a timeless classic. It’s evident when you start reading with children, some books just sing.

Perhaps the job of a good commercial artist is to try and incubate whatever truth or vitality that was present at the inception of their project all the way to the end. That’s not easy with so many other stake holders, it is absolutely a collaborative exercise and publishers need to react to markets and trends. But I believe there is a craft to it that can be practiced and nurtured, it’s tacit in great writing and pictures. The only work I ever really like of my own are the tiny moments of truth and play that occur outside of knowing or trying. The real craft is how to extract and realise such moments into fully formed books. Wish me luck.

Back to News Page