Authoriality, Copies, and Image-Makers in the Age of 3D Reproduction

Serkan Özkaya, David (inspired by Michelangelo). Statue under construction in government building (also under construction). Istanbul, Turkey, 2005. Photo by Baris Ozcetin (Wikimedia Commons)

Continuing the Obsession theme of Varoom 25, Pablo Soler-Jones examines our changing relationship with the image in the digital age, in a review of the paperback release of Double: Storefront for Art and Architecture Manifesto Series 2. Designed by Pentagram, featuring a variety of different thinkers and artists discussing Architecture, Images and notions of Authorialism, Soler-Jones extracts some future-facing questions around the role of the image-maker in the age of the digital copy and the emergent world of 3D printing

Since the 1960s doubles, copies, remixes and reproductions have been a central concern of the discourse surrounding art. Now thanks to the Internet, appropriation has become the norm, and our relationship with the double needs an update. Double is the latest instalment from Storefront for Art and Architecture’s Manifesto Series, and within its pages it feels like this conversation is taking on a new, revitalised form. The publication is the result of an event held by Storefront where a “group of artists, architects, critics, historians and theorists, discuss the effects, desires and implications in the act of doubling, replicating or copying.” 1

Flipbook Images: pp. 1–163. Images of Serkan Özkaya’s David being transported through New York City, 2012. Photos by Brett Beyer.

Its varied roster gives the book an unusual status, somewhere between criticism and expression. The group is comprised of: Curator and Writer Christopher Eamon; Cristina Goberna who is part of Fake Industries Architectural Agonism; Alanna Heiss, Director of ARTonAIR.org and the Clocktower Gallery; art and architectural historian Spyros Papapetros from the Princeton School of Architetcure; editor of Hyperallergic Hrag Vartanian; architect and theorist Ines Weizman; and Serkan Ozkaya a contemporary conceptual artist.

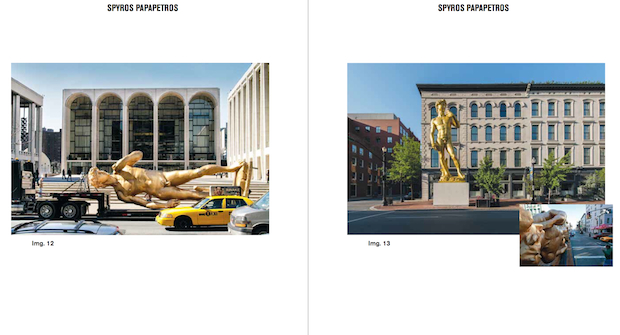

Once the chosen medium for the war cries of the Avant-Garde, the manifesto format itself feels like a throw-back, a reincarnation that points backwards to an archaic past, whilst projecting onward into the future. Designed by Pentagram, the book plays out the textual narrative in physical form, giving the text another dimension. The book spine acts as a mirror, the front cover image reflected on the back. The untrimmed pages give the fore edge a / shape enforcing the mirror image and providing a novel page-flicking experience.

Each piece varies slightly in design; there is no dominant guiding voice. Instead the book, as mental framework, emerges as a semi-stable whole, from the interactions between these distinct parts.

The book’s compact, almost pocket-size makes it feel to the point. The first half is comprised of succinct essays, compact packages of information. The second half takes on a different form, made up of transcriptions of several conversations around three paella dinners, leaving the finale feeling more open ended. In his introduction Serkan Ozkaya writes, “The end of an essay, or a book, though formulated as if it were an end, is therefore not really an end but a transition point that has received undue weight.” Each speaker in the final section is marked by small icons – triangles, crosses, stars etc – partially concealing their identity; a recognition of the congregational effort behind the publication.

1960s – 1980s: Serial Repetition, and Representation

In his 1936, Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction, Walter Benjamin discusses the loss in the reproduced image of an aura previously held by the original artwork.2 Even then, it was seen as partially positive, offering possibilities for the politicization of art; its emancipation from dependence on ritual, and its institutional chains.

![]() Two decades later, Andy Warhol, prolific serial doublist3 par excellence, put Benjamin’s ideas to the test. Following a successful career as commercial illustrator, Warhol drew on his experience and put it to the service of becoming an artist. He is key in moulding the landscape of the discussion on ‘doubles’. Warhol’s name appears throughout the text and his presence, like a phantasm, is a yardstick looming over the wider conversation.

Two decades later, Andy Warhol, prolific serial doublist3 par excellence, put Benjamin’s ideas to the test. Following a successful career as commercial illustrator, Warhol drew on his experience and put it to the service of becoming an artist. He is key in moulding the landscape of the discussion on ‘doubles’. Warhol’s name appears throughout the text and his presence, like a phantasm, is a yardstick looming over the wider conversation.

In 1962 Warhol opened his Factory in midtown Manhattan. Seen as a reaction to the glorifying of the individual by the Abstract Expressionists, Warhol sought to diffuse authorial agency. Through his appropriation of the classic notion of industrial production (the Taylorist assembly line) with an army of assistants of which he became ‘hyperbolic’ manager, and using mechanical reproduction, Warhol sought to remove any trace of the artist’s hand and ultimately become a machine of mass production.

This kind of symbolic self-sacrifice, the bypassing of traditional ideas of sole authorship, spreading out into the collective, turned out to be a sure-fire way of speeding up his acceleration towards becoming an individual cult figure. 4

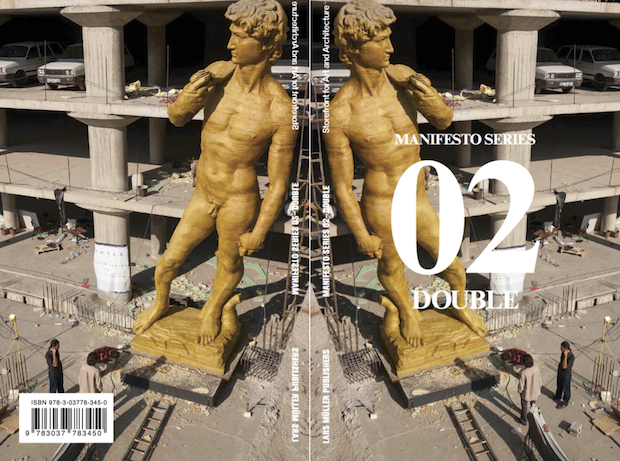

p.22 Stills from P. Diddy vs. Mona Lisa. Incubate blog. 2010

p.23 Copy of Mona Lisa in Dafen, China. 2011. Photo by Michael Mandiberg (Flickr Creative Commons)

The aura of the original artwork, which Walter Benjamin talks of, was lost in the reproduced images that came out of Warhol’s factory. The most widely reproduced ‘image’ was that of Warhol himself – he became an image, reproduced in mass media and the collective consciousness. The aura had mutated into a personality cult, created by a new kind of scarcity and uniqueness. The Factory was first and foremost a social factory producing social relations. It produced the scarcity of the ‘in-crowd’, with Warhol’s status as a celebrity, aloof, separated from the masses, largely inaccessible.5

If superficially Warhol’s production process created some sense of imagery being made by a collective agency, it was a twisted kind of collectivity, one that relied on the persistence of hierarchies, placing Warhol firmly on top. People still spent millions on “Warhol’s”. He used his celebrity status as a tool to give his ‘Superstars’, those who should be so lucky, their fifteen minutes of fame. He used his mythological character to take objects from the everyday, Brillo pads and cans of soup, and elevate them to the level of art – ultimately the product was Warhol. 6 The materiality of the objects themselves became abstracted and almost inconsequential.

Fast-forward two decades and the work of French philosophers and theorists of the 1960s such as Derrida, Barthes, Lacan, had now become more widely accessible through english translations, filtering through into the New York 1980s art world. Artists continued to be preoccupied with the omnipresence of representation, decoding and recoding the world through the idea of doubles and copies.7

Images and objects were ‘signifiers’, always pointing away to something else. Alan McCollum (an American artist discussed by critic Christopher Eamon in Double) working in New York in the 1970s and 1980s questioned the notion of art objects as possessing unique value derived from their rarity. His Surrogates – a seemingly infinite set of plaster-cast, monochromatic, framed pictures – are substitutes for other paintings.

‘The surrogate fulfils the task of painting: it facilitates aesthetic engagement and economic exchange, produces discourse, and takes up space on the wall. It does all the things that a painting should do. But it is not a painting. It is a fraud, a fake, a stand-in’. 8

So here objects, things, artworks are loaded with social content, deployed by people to signify what they please but left feeling empty. As things in themselves, they are just shells. It is all about the people. Ideas of collectivity seemed dominated by hierarchical power structures, with a select few enjoying their success sat in comfortable thrones in the vista suite of life, using objects as foot rests and fashion statements.

Autonomous Objects and Versions

Now in the 21st Century a new mental space has been created partly by the Internet and 3D reproduction technologies. The basic functions of web 2.0 have now become so deeply ingrained in our lives, so ubiquitous, they have become a banality. 3D scanning and printing have extended the reach of mechanical reproduction beyond photographic images into the sphere of objects. Here traditional notions of representation are reversed where physical 3D prints of digital objects become representations. 9![]()

The work of Serkan Ozkaya, a 41-year old Turkish conceptual artist dealing with ideas of appropriation, helps to establish some important themes in the book and offers a starting point from which to rethink the notion of the Double.

On the front cover of Double there is an image of Ozkaya’s Double David, the project which acted as a catalyst for the book in the first place. It is a double in that it is a replica of Michelangelo’s David and it is double the size – it’s massive. It is made of polystyrene and painted gold, perhaps a wink at Warhol and Pop Art. Spyros Papapetros, helps to unpack Ozkayas work in his piece Animated Doubles10, a title that for me sums up this new direction perfectly.

In Double David, as with the doubles of the late 20th Century, there is an absence of the artist’s authorial gesture, but in this case it has been pushed even further, to a more pervasive absence of human agency in general. The power has been shifted to the technology. The sculpture has been created by collective digital and mechanical process; laser beams and electrical currents fraternise, perfectly scanning every detail of the original sculpture and generating a digital 3D model which is then cut into hundreds of Styrofoam pieces generated by a milling machine. ‘His David is essentially neither his nor Michelangelo’s.’ 11

It is never permanently installed and online it exists as photographs documenting its transit; it is always on the move like any good copy should be. Online, the aura of the original is replaced by a value defined by velocity, intensity and spread.12 In order to stay alive, images must circulate or they will fade back into the cloudy depth of history, further and further down that endless scroll.

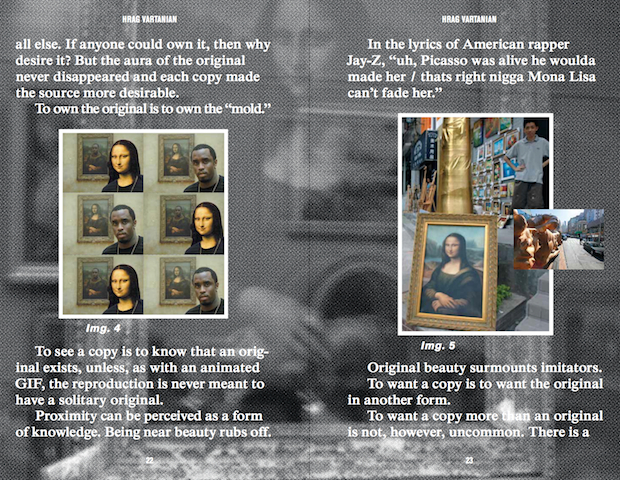

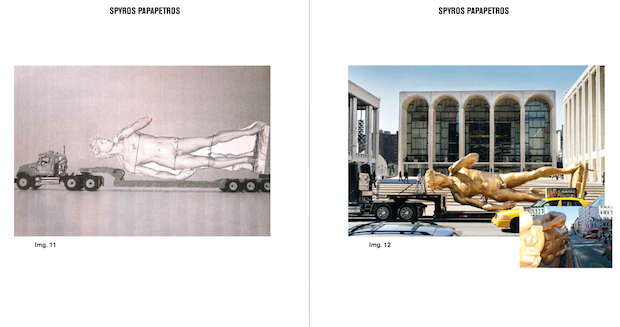

pp. 61-62 Image 11. Serkan Özkaya, David (inspired by Michelangelo), on top of a motor truck, drawing. 2012

Image 12. Serkan Özkaya, David (inspired by Michelangelo), in front of Lincoln Center, NYC, March 2012. Photo by Brett Beyer.

Pentagram here once again gets inside the book, cleverly supplementing this idea of continuous motion. Images of Ozkaya’s Double David in transit, on the back of a lorry, create a sub-narrative, running through the book like writing on a stick of rock. The images are all taken from the same vantage point, each version altered slightly by its context, inside the photograph: the lighting conditions, a yellow taxi, a man crossing the road or on the page: an overlapping line, an adjacent image or endless black.13![]()

It is no longer a case of using ‘appropriation’ as an end or as critique. As with most allegedly anti-capitalist gestures, the anti-authoritarian edge ‘appropriation’ or ‘the remix’ once held, has been largely appropriated by capitalism itself. Copyright wars are seen as hysterical. Appropriation is just what happens now, and in itself does not challenge traditional notions of authorship; in fact it keeps them very much intact. The remix is a celebration that pays tribute to the original source.

The possibilities for distribution opened up by the Internet, free-up information from its reliance on institutional frameworks, based on hierarchical models of creation and mediation. Traditional notions of individual authorship begin to be displaced in the idea of the progressive version, a term borrowed from Oliver Laric.14

p. 65 Image 13. Serkan Özkaya, David (inspired by Michelangelo), installation in Louisville, Kentucky, April 2012. Courtesy of 21c Museum. Photo by Magnus Lindqvist.

Users become distributors and curators. Creative agency is decentralised, diffused to the collective. Ideas of intellectual effort as private property are challenged, as sources of authorship are often the first bits of information to be lost as an image is edited, reformatted, cropped, combined, compressed, transferred, downloaded and re-uploaded. A progressive version is not an endpoint; it is a node in a network of trajectories that defy patrimony and spatial fixity. It is about ‘endless process and eternal mediation’. 15

With this, a new kind of public space begins to emerge unconstrained by bureaucratic exclusion.

New public space

The lack of human agency in Oskaya’s David feels like an exciting direction for conversations surrounding the copy to be heading in and seems to be symptomatic of something that is in the air more generally.

In recent years a new way of thinking has been emerging that reconceives man’s relation to matter and the world of things. Loosely positioned under the umbrella terms of ‘Speculative Realism’ or ‘New Materialism’ it offers an escape from anthropocentric worldviews. Objects, previously subjugated to the thinking human, come forward as a new kind of autonomous entity; things become active participants in social life.

![]() This goes beyond the democratization of information for humans as offered by the Internet, into the democratization of the physical world for all parties. A more ecological way of thinking can help us better appreciate how non-humans play active roles in shaping the reality around us.

This goes beyond the democratization of information for humans as offered by the Internet, into the democratization of the physical world for all parties. A more ecological way of thinking can help us better appreciate how non-humans play active roles in shaping the reality around us.

We can begin to see things as autonomous, as having agency and the capacity to make things happen outside of the roles that humans give them. This shift in perception is perhaps catalysed by the scale of global problems – atmospheric pollution, global warming, rising sea levels – we face at the moment. These are very material processes driven by non-human entities which are often too massive, and slow for us to directly perceive. With this, we shift towards a more inclusive notions of collectivity.16

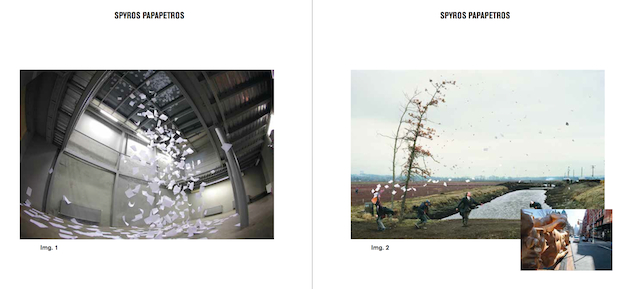

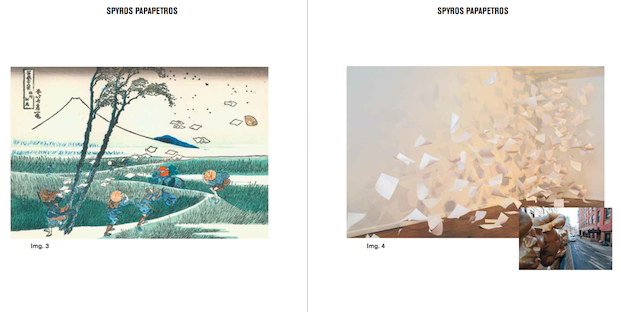

p.34 Image 1. Serkan Özkaya. A Sudden Gust of Wind. Bilsar Building, Istanbul, 2009. Photo by Baris Ozcetin. p.35 Image 2. Jeff Wall. A Sudden Gust of Wind (after Hokusai). Transparency in light box. Tate Gallery, London, 1993. Image courtesy of Tate Gallery.

In Ozkaya’s A Sudden Gust of Wind we glimpse the vitality of things, a precarious assemblage of A4 paper sheets frozen in a violent burst of motion. Their blank anonymity, standardized dimension and spaces in between, all mirror each other exponentially. Unlike Hokusai’s or Wall’s work from where the title is taken, here there is no external agent, no wind, or people, the vitality and dynamism is all the paper’s. A collective autonomy from within the swarm.![]()

If we start to take notice of the role of objects as sovereign bodies we have to shift our idea of who and what continues a public or public space. We also need to open up ‘new procedures, technologies, and regimes of perception that enable us to consult nonhumans more closely, or to listen and respond more carefully to their outbreaks, objections, testimonies and propositions.’17 In her piece for Double, Ines Weizman suggests one possible stage on which this communication can be played out – the court room.

Weizman argues for a shift in (architectural) copyright away from the right of the human, maker or author towards the rights of the building itself.

It is a call for humans to step back, recognising buildings as a new kind of subject, asked to come forward and perform within the courtroom, ‘not presented but representing.’ Humans become facilitators. It is recognition of the agency of buildings above and beyond their ties with any sort of human authorial control. ‘Buildings need humans like humans need a bottle of wine.’18

p. 38 Image 3. Katsushika Hokusai. Ejiri in Suruga Province (A Sudden Gust of Wind). Color woodcut. 1830–33. Image courtesy of Trustees of the British Museum.

p. 39 Image 4. Serkan Özkaya. A Sudden Gust of Wind. Boots Contemporary Arts Space, St. Louis, Missouri, 2008. Image courtesy of Boots Contemporary Arts Space.

This is an exciting idea, but, is the institutional framework of the juridical system with its reliance on heavily codified ways of doing things, the place for this change in perception to take place? What would Lady Justice with her blindfold and predilection for human language make of it?

This shift in perception leads to a reconsideration of what authorship is and how work is created. Andy Warhol, who despite allegedly going against the cult of the artist-genius of previous generations, remained in the eyes of the public the ultimate producer. Now the artist’s role shifts towards that of facilitator, guardian or conduit.19 ![]()

With this notion, art practice falls in line with the logic of the copy-in-motion – in its constant state of flux, practice becomes occupation, an endless process. 20 The spatial boundaries separating creator from product, work and not-work become blurred. Practice becomes a trajectory, a performance, collaborative in a new way, bringing in all stakeholders. There is no clear beginning or end.

In this way artwork becomes a new kind of public space in itself. It results from the congregational agency of the technological, biological, mineral and all their duplicates. The artwork becomes an assemblage, made of smaller, heterogeneous interacting parts all of which have their own capacities to make things happen, but that become stronger in allegiance.

The ‘Trans-‘

So the role of doubles, copies, and reproductions today is to break free from their ties to an all-pervasive human dominance; to activate and bring forward the autonomy of non-human entities. The Double is now an exercise in blurring boundaries.

And although there is still a need for the prefix Re- to say or write about reproduction, repetition, remixing and replication, perhaps in spirit, as activities, they seek a subtle shift in prefix towards Trans-: a recognition of continuous flows of energy, constant flux and porosity between separate entities. With the mental and physical space advanced by new technologies everything is infinitely reproducible and nothing is fixed. The aura lost with the original has been replaced by the need to just keep moving.![]()

The book offers a way into the conversation. Although composed of manifestos, seemingly concrete, final statements, it proposes new questions and offers points of departure. The status of the Double or the copy is fraught with ambivalence. It emerges as a process, a performance, a reincarnation, a sign, a fake, an evil twin, a means, an end, or even as an original.

Double: Storefront for Art and Architecture Manifesto Series #02

Lars Muller Publishers

176 Pages

GBP 12

Buy here

Pablo Jones-Soler has been researching the changing role of objects based on the work of thinkers such as Manuel De Landa, Jane Bennett, Bruno Latour and Graham Harman. His practice currently focusses on lifestyle strategies for personal and planetary wellbeing. He is in his final year at Camberwell. Find out more about Pablo Jones-Soler’s work here

References:

1. Storefront for Art and Architecture, Manifesto Series: DOUBLE, http://www.storefrontnews.org/programming/series?c=&p=&e=467

2. Benjamin, W. and Underwood, J. A. 2008. The Work of Art in The Age of Mechanical Reproduction. London: Penguin.

3. Allanna Heiss refers to Warhol as a serial doublists in: A Call For The Reenactent of Something That Never Actually Happened, conversation transcript/ essay in Double.

4. from Lets Ask The Question Differently, conversation transcript/ essay in Double.

5. Groys. B, Self-Design and Aesthetic Responsibilit,y http://www.e-flux.com/journal/self-design-and-aesthetic-responsibility/

5. Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F. 2012. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

6. Caplan, L, Framing Artwork, http://www.e-flux.com/journal/framing-artwork/

7.Eamon, C. Double a Theory, in Double

8. Starke. T, Allan McCollum, http://allanmccollum.net/allanmcnyc//McCollum-Starke.html Originally published in:This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s

9. It is also worth noting the changing role of photography. Once a purely mechanical process, light imprinted on a photosensitive surface, photography conferred a means of ‘self delineation of objects,’ ‘of statement without syntax.

10. Animated Doubles, Essay in Double

11. Animated Doubles, Essay in Double

12. Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F. 2012. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

13. Vartanian, Holy Holy Copy Copy Culture Culture: a Manifesto, essay in Double

14. Troemel. B, The word Remix Is Corny, http://dismagazine.com/author/brad-troemel/

Although Oliver Laric does not feature in this publication, the sentiment behind his definition of the word version is felt throughout the book, and it is therefore a useful term with which to capture that.

15. Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F. 2012. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

16.De Landa, M. Manuel De Landa In conversation with Timur Si-Quin http://timursiqin.com/2012/siqin_inside_070612_final_NEU_web-spreads.pdf

17. Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant matter. Durham: Duke University Press.

18. Weisman. I. Manifesto for the rights of architecture.

19. Vartanian, Holy Holy Copy Copy Culture Culture: a Manifesto, essay in Double

20. Steyerl, H. and Berardi, F. 2012. The Wretched of the Screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Back to News Page