The Varoom Report: The Muse V20

The Muse

THE ILLUSTRATION REPORT Winter 2012

ISSUE 20

While ‘inspiration’ often simply means context-free imitation of style, the true Muse has many sources. Varoom discovers that The Muse is a powerful mix of critical reflection, hard work and love.

The magic of The Muse is in the strange power of focus given by a mug of tea, in the trusted observation of a colleague, in the rich research and planning that informs and narrates the creative process. Most of all The Muse is about acquiring the critical tools, the understanding of context to step in at the right moment in the process and make a productive decision. And then take an inspiring slurp of tea. Editor, John O’Reilly introduces this issue:

1.1 Knowledge and Mystery

In the tradition of the Muse as female, as a portal for a male to access that female part of his sensibility which enables creativity, the best place to start writing about the Muse is the Muse on the cover by Aude Van Ryn. This image captures two other essential and contradictory aspects of the Muse – Knowledge and Mystery. The Muse gives the artist insight into creative process, inhabits the creative process, while at the same time preserving distance, the aura of mystery. Mystery as a condition of Knowledge.

Cover illustration by Aude Van Ryn

1.1 Visual Signifiers

Like Van Ryn’s image, we can pick out the signifiers, the face of the Muse herself, the apple of knowledge, but the texture of her dress, the angular shapes flowing from the side of the frame become narrative detail that inspire and provoke questions. They function as the reader’s Muse.

1.2 The Original Muses

Originally, for the Greeks, Muses were almost modernist in their specialisation, there was a strict division of labour, no multi-tasking postmodern Muses here. The Greeks had nine Muses (Plato suggested Sappho as a tenth) each personifying an art or science, from Calliope the Muse of Epic poetry, to Terpsichore the Muse of dance, to Urania, the Muse of Astronomy.

1.3 Creative Exchange

The age of the Muse, of the flesh and blood Muse, has perhaps passed. In some respects this is no bad thing. The Muse could often be a license for selfish behaviour on the part of men – from Klimt to Picasso. Neil Gaiman magnifies this relationship in his graphic novel series The Sandman which features a dark, cruel tale called Calliope, in which a writer captures a Muse, imprisons her and rapes her in a brutal search for inspiration. There is revenge. Gaiman’s tale is an extreme example of what appears to be an unequal economy of male and female in the history of the muse. She inspires, he’s handsomely rewarded. Yet traditionally she is immortalised in paintings, song, or poetry, trading off the uniquely peculiar relationship for an eternity of fame in an art form.

2.1 The Face

The flesh and blood Muse lives on, creatively and commercially in the world of Fashion and fashion photography. In The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion, a book accompanying the 2009 show of the same name at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, Curator Harold Koda writes, “to be sure, the process through which an individual comes to inspire a generation to embrace the latest trends or to accept an altered paradigm of physiognomy and physique can be reduced to certain elements in the creation of the editorial photograph – the talent of the photographer, the prescience of the sittings editor, the imagination of the stylist, and the virtuosity of the hairstylist and make-up artist. But ultimately, it rests in the conformity of an individual’s physical attributes to the zeitgeist.” The aura of ‘the Face’ exerts a powerful allure especially when an industry is structured around it.

2.2 Muse Demystified

But the idea of the Muse doesn’t sit very easily with the age of science. At the beginning of the 20th Century, Freud’s psychoanalysis gave a plausible if occasionally nuts-and-bolts demystification of the process whereby sexuality sublimated became artistic endeavour.

2.3 Beauty and the Brief

And what about the commercial artist, the illustrator whose Muse is the practical, plain-speaking, brief. The brief which is neither beautiful or handsome nor an object of desire, yet the professional illustrator needs to deliver something beautiful and professional. Unless you’re sending flowers to your Art Director, or they are sending flowers to you, you need to create on a daily basis without a flesh-and-blood Muse to inspire the creative emotions.

3.1 Sentimentalism

It’s why the second Mokita illustration symposium was so compelling in its exploration of the idea of The Sentimental Gene. Sentimental is a word whose negative connotations asserts a lack of sophistication, a kind of emotional vulgarity, and worst of all in 2012-2013 sentimentality is the definition of the emotionally ‘inauthentic’. ‘Authenticity’ is serious, ‘Sentiment’ is shallow. “A sentimentalist,” declared Oscar Wilde, “is simply one who desires to have the luxury of an emotion without paying for it.” According to Wilde there’s an economy of emotions, where we always need to balance the books. No unearned emotions, no psychological freebies.

3.2 Economy of the Sentimental

But the circulation of goods in modern economies, and large swathes of social interaction are built on the sentiment of illustration – packaging, birthday cards, Christmas cards, wrapping paper, book covers, fashion, even banknotes as those opposed to the Euro defended their patriots around the image of the Queen of the currency… Even materials have a kind of sentimentality as illustrators well know, and have been very successful exploiting the idea of printed matter in a digital culture, that it feels ‘truer’, more ‘honest’, more tangible.

3.3 Soap Opera of Illustration?

Is Sentiment the illustrator’s creative friend, the essential muse for communication, a kind of plastic psychological material for visual creativity, or is it a lazy default, a formula, a set of well-worn codes guaranteed to please undemanding clients. Is sentimentality simply the Soap Opera of Illustration?

3.4 Empathy

Darryl Clifton (one of the organisers of Mokita along with Roderick Mills and Geoff Grandfield) argues in Illustration: A Case for Blackmail that sentimentality is an essential aspect of visual communication, “If sentimentality is the means through which the idea flows then empathy is its engine. The illustrator’s ability to understand their audience, to consider and subsequently manipulate a response with the skilful use of visual language is key in this respect.” A key example cited by Clifton is Laura Carlin’s Iron Man with its “robust, intellectual sentimentality.”

4.1 Emotion recollected in tranquility

In a similar way that the idea of the “Imagination” itself was the Muse for the Romantics of the 18th and early 19th Century, Sentiment is the Muse of the contemporary illustrator. “Poetry”, William Wordsworth wrote in the preface to Lyrical Ballads, “is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin’s from emotion recollected in tranquility.” If, as it has been suggested, Fine Art is simply extreme shopping for the one per cent (Dear Claes, Frieze magazine, issue 148), Illustration is arguably the contemporary visual discipline of the sentimental, the vital means to connect more deeply with modern life. No matter how pragmatic we need to be about creativity on a day-to-day basis, about getting the job done, the reality is that there’s always a heightened emotional component to the process.

4.2 Naked Emotion

Roderick Mills and Jasper Goodall reflect on emotions and creativity in their feature In The Crit. Artist Lisa Yuskavage who graduated from Yale in 1986, told The New York Times in a feature on the Crit, “Think about the general nightmare of standing nude in public… But add something else you fear, like standing nude on a scale.” The Crit is analytic but it’s also unavoidably emotional.

Yuko Michishita

4.3 The Crit vs. ‘Like’

When students are paying more for college courses, leaving as a graduate with significant debt to uncertain career futures, the Crit is a valuable Muse that is unavailable elsewhere. And yet as Mills and Goodall point out, this core structure of Art and Design education is facing challenges from other cultural and social forces. “The modern Illustration student is bombarded by visual imagery through the Internet,” write Mills and Goodall. The issue is not just the availability of online, context-free imagery, which students measure their work against. Students, “post work almost immediately after completing, to a barrage of opinion and the generation of ‘Like’ provides instant feedback – whether this is an informed viewpoint or not.”

4.4 Style Pressure

And there are economic pressures too. “In the final year of a degree course,” write Goodall and Mills, “there is the constant pressure of the world outside, and a degree show, leading to some to see the final year as a time for finessing their ‘style’ rather than continuing to develop as a practitioner through experimentation. Not easy with the need to pay back tuition fees and the realisation that career paths are less linear these days.”

5.1 Prescribing a Muse

There is however a perfect Muse to counteract misplaced desire for perfecting style. “Over the past 20 years,” says Mack Manning, Senior Lecturer at Manchester School of Art, in The Source, Desdemona McCannon’s feature on Polish image-making, “I have prescribed 1970s Polish poster imagery like a Super Vitamin for my students, and doses of Andrew Klimowski and Hanna Bodnar always cure stubborn cases of visual stage fright and students early preconceived notions of representation.”

5.2 Unrepresentable Emotion

Polish illustration and graphics is venerated in the world of commercial art. There’s a magnetism in its surrealness, its oddity, a visual dialect that’s all the more compelling because it hasn’t learned the mainstream language – or even conceived of itself as a ‘language’, as it emerges in pictures that often seem to present an idea or emotion that feels unrepresentable. Which is why these images are often disturbing to an eye calibrated by governing styles.

Theatrical Poster forMarysia i Napoleon, Henryk Tomaszewski, 1964

5.3 Hardship Muse

Desdemona McCannon explores the productive and unproductive mythologies that have emerged from our fascination with Polish imagery. Such as the ‘romantic’ idea that great art is always born in difficult situations, in this case censorship and political repression. McCannon casts a cool eye on the idea that suffering is a Muse, “for the most part, the fear of reprisal and hardship quietens the desire to express oneself openly.”

5.4 The Muse of History

But we don’t need to travel to find a Muse. In his book On Illustration, Andrzej Klimowski (who features in McCannon’s article), registers a Muse that’s much closer to home. Our personal and social background, family, geography, are the brute materials of our life, that determine our lives, that make our history, determine our future, our destiny, until we think about it, reflect on it, use it as a Muse. Klimowski tells a story about designer and illustrator Scott Santoro who came from a family of plumbers, and everyone assumed he would become a plumber, but he shaped his background in a different way. “Plumbing”, writes Klimowski of Santoro, “had an influence on his design and illustration work. Letterforms, collages and page layouts were influenced by the aesthetics of waste pipes, drainpipes, S-bends and gutters. He even carried his designer’s materials in a handyman’s toolkit when visiting his clients.”

6.1 From Pop Art to eBay

The Ancient Greeks had to invent Muses, whereas we are surrounded by things, stuff, objects, that function as Muses. John P. Lowe discusses the Significant Objects project, a series of works inspired by stuff on eBay. While in Illustration and Sustainability, Derek Bainton asks questions about the demise of Natural History Illustration, exploring the Ghosts of Gone Birds project which seeks to raise consciousness through illustration of our lack of awareness of conservation issues.

6.2 The Muse of Shiny Things

This piece is also a reminder of the classic idea of the designer as Magpie. Of all the birds a profession could be identified with, the Magpie is a deeply troubling one. The idea that one is seduced by shiny things. The Magpie sensibility doesn’t explore the wider context of shiny objects. It’s why we get graphics and illustrations that are imitative in a dull, unshiny way.

6.3 Seduction

And seduction and insight are not mutually exclusive. Re-reading Marian Bantjes book, I Wonder, with her explorations of IKEA bookshelf construction, gravestones, her Mum’s notepads, is a reminder that seeking the Muse in the life around you, illustrating and designing it with craft and beauty, can go hand-in-hand with research, evaluation and judgment. Seduction is an art not a formula.

6.4 Understanding Spots Opportunity

It’s a reminder that we have a surfeit of inspiration, on blogs, tumblr, quick-fire projects and not enough context. While the link between academic theory and professional practice remains a challenging one, it’s also clear that the future belongs to illustrators whose work is valued by commissioners or consumers as ‘different’ because they understand what Harold Korda calls ‘the zeitgeist’, and can spot the commercial opportunity that comes with it. To exploit those seductively cool styles, materials, technologies, to learn from them, to give them effective communication value we must understand what they do, what their visual, emotional, psychological impact is.

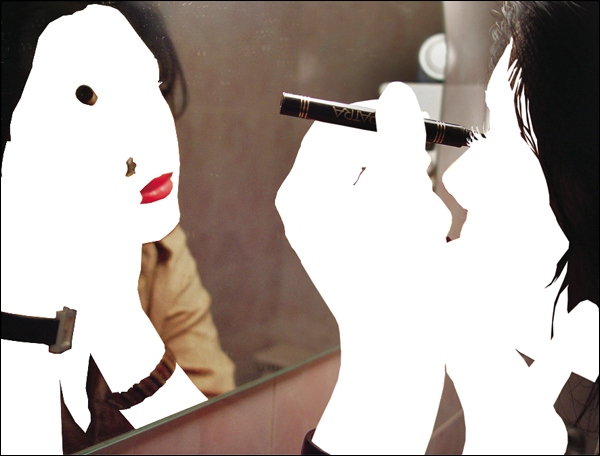

6.5 From Cool to Context

Like the image above, the figure cut out, a human-graphic. It’s kind of cool, cool enough to be filed away as a style moment. The image is by Iranian designer and artist Amirali Ghasemi, whose work Tehran Remixed is currently part of a group show at London’s V&A. Yet it’s helpful to understand the impact of the image to think through the significance of concealment, and stolen pleasures, in contemporary Iran where women’s bodies in imported magazines are blacked out. The Muse demands understanding.

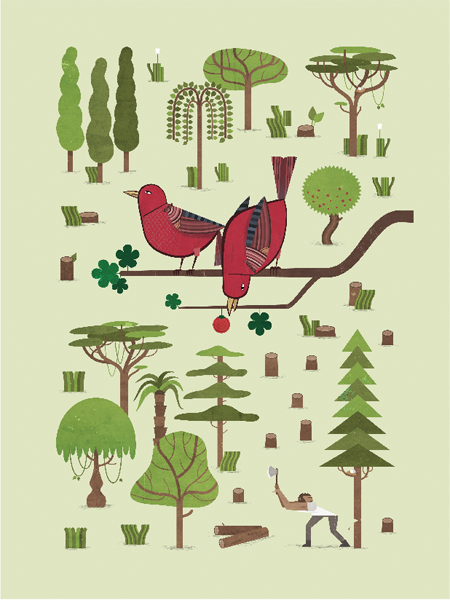

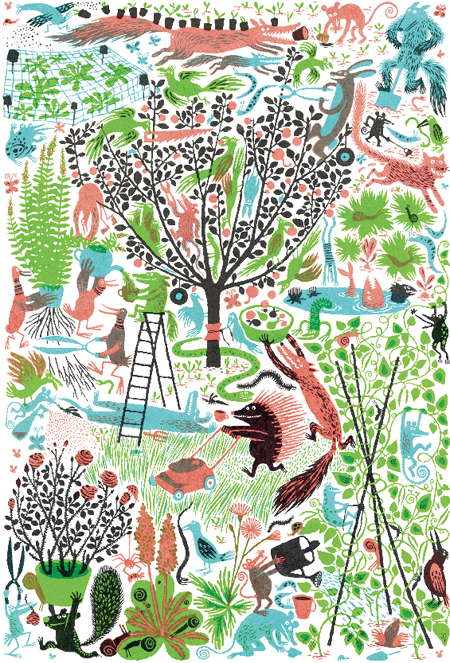

6.6 Nurturing The Muse

So when Katherina Manolessou, who created an image on ‘Gardening’ for the Ted Baker British Pastimes project, showed her final work to a fellow gardener it wasn’t the end of her research, “when I showed this to a friend who is a brilliant gardener, she pointed at the hedgehog mowing the lawn and directed me to Philip Larkin’s poem The Mower. I now always think of Larkin’s hedgehog when I garden.” We need to nurture and be kind to our Muse, to our creative intelligence, unlike Larkin’s mower who doesn’t pay attention to the animal, killed by the blades.

To purchase Varoom 20 go here

Back to News Page