Varoom Activism: Manifesto for Illustrators

‘What use is illustration? What good can it do?’

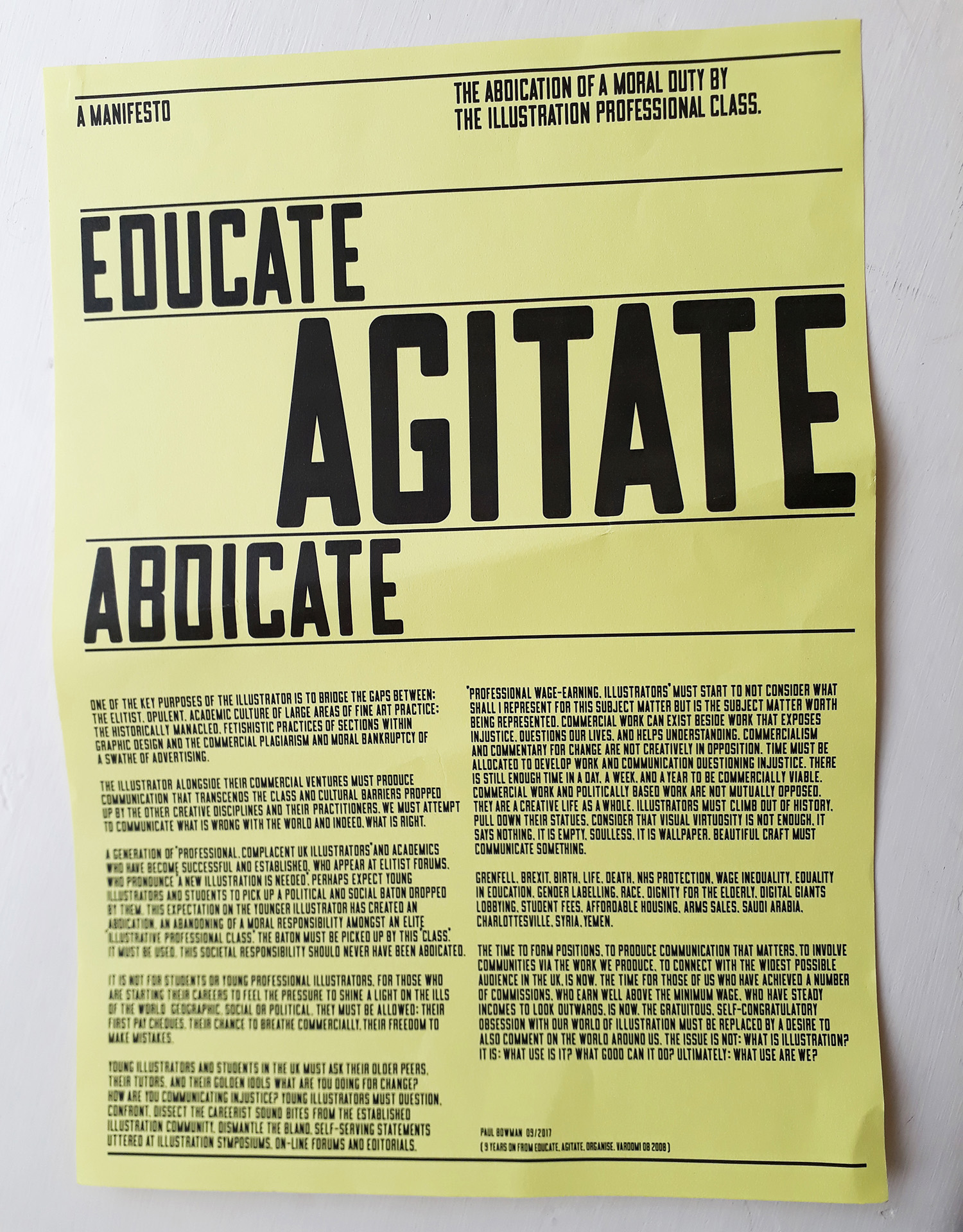

Shortly before he died in November 2017, educator and illustrator Paul Bowman sent out a densely worded poster entitled Educate Agitate Abdicate, which was a manifesto and call to arms for illustrators, emphasising that ‘We must attempt to communicate what is wrong with the world and indeed, what is right.’

His text accused a comfortable ‘elite illustrative professional class’ of abandoning a moral responsibility to address political and social issues. Described as a ‘critical friend to illustration’ by Brighton University Course Leader Roderick Mills, as an artist and illustrator Paul worked across print, animation and interactivity and taught as Course Director for Illustration and Visual Media at London College of Communication UAL, and later as Visiting Lecturer at University for the Creative Arts Epsom. His recent artwork had included a three dimensional piece examining the dominant issues around destruction in West Asia.

‘Der Kessel.” Paul Bowman

“My contention is that good creative work sheds light on something not seen, something not known’” he said in a 2008 issue of Varoom, “It causes us to re-evaluate our lives, our society and ourselves. Good creative work challenges the viewer to question things. The subject matter is served by the style not the other way round, and the first question asked should be – is the subject matter any good?”

As a member of the Varoom Editorial Board Paul offered a valuable voice to the magazine and his deeply held view that illustration is a valuable a tool for commentating on the world, was one that carried through to this Manifesto:

Educate Agitate Abdicate

The abdication of a moral duty by the illustration professional class.

One of the key purposes of the illustrator is to bridge the gaps between: The elitist, opulent, academic culture of large areas of fine art practice: the historically manacled, fetishistic practices of sections within graphic design and the commercial plagiarism and moral bankruptcy of a swathe of advertising.

The illustrator alongside their commercial ventures must produce communication that transcends the class and cultural barriers propped up by the other creative disciplines and their practitioners. We must attempt to communicate what is wrong with the world and indeed, what is right.

A generation of ‘professional, complacent UK illustrators’ and academics who have become successful and established, who appear at elitist forums, who pronounce a new illustration is needed, perhaps expect young illustrators and students to pick up a political and social baton dropped by them. This expectation on the younger illustrator has created an abdication, an abandoning of a moral responsibility amongst an elite ‘illustrative professional class.’ The baton must be picked up by this ‘class’. It must be used. This societal responsibility should never have been abdicated.

It is not for the students or young professional illustrators, for those who are starting their careers to feel the pressure to shine a light on the ills of the world geographic. Social or political. They must be allowed: their first pay cheques, their chance to breathe commercially, their freedom to make mistakes.

Young illustrators and students in the UK must ask their older peers, their tutors, and their golden idols what are you doing for change? How are you communicating injustice? Young illustrators must question, confront, dissect the careerist sound bites from the established illustration community, dismantle the bland, self-service statements uttered at illustration symposiums, on-line forums and editorials.

‘Professional, wage-earning illustrators’ must start to not consider what shall I represent for this subject matter but is the subject matter worth being represented. Commercial work can exist beside work that exposes injustice, questions our lives, and helps understanding. Commercialism and commentary for change are not creatively in opposition. Time must be allocated to develop work and communication questioning injustice. There is still enough time in a day, a week, and a year to be commercially viable. Commercial work and politically based work are not mutually opposed. They are a creative life as a whole. Illustrators must climb out of history, pull down their statues, consider that visual virtuosity is not enough. It says nothing. It is empty, soulless. It is wallpaper, beautiful craft must communicate something.

Grenfell. Brexit. Birth. Life. Death. NHS protection. Wage inequality. Equality in education. Gender labelling. Race. Dignity the elderly. Digital giants lobbying. Student fees. Affordable housing. Arms sales. Saudi Arabia. Charlottesville. Syria. Yemen.

The time to form positions, to produce communication that matters, to involve communities via the work we produce. To connect with the widest possible audience in the UK, is now. The time for those of us who have achieved a number of commissions, who earn well above the minimum wage, who have steady incomes to look outwards, is now. The gratuitous, self-congratulatory obsession with our world of illustration must be replaced by a desire to also comment on the world around us. The issue is not: What is illustration? It is: What use is it? What good can it do? Ultimately: What use are we?

— Paul Bowman, 2017

Paul Bowman Award

The family of Paul Bowman donated several important campaigning art pieces of his to the University for the Creative Arts Epsom course, connected thematically to his bêtes-noires of repression of independent media voices, and which are now on permanent display in the course areas.

To celebrate the man and his legacy of design engagement, the university set up an annual award in his name, which celebrates the influence of a cherished teacher, colleague, writer and educator. The first award was given to Alyssa-Tara Watling in 2018. Alyssa’s winning piece, ‘The Real Big Issue’, is an editorial work exploring issues surrounding gentrification, using gently teasing imagery in the Chas LaBorde canon.

Epsom students by Paul Bowman artwork, 2018

‘What is design? What use is it? What good can it do? What use are we?’ These questions of Paul’s are central to the qualities the annual award seeks to recognise. Juried by students on the course, the award celebrates the work of a graduating Graphics student who best upholds the principles of social engagement outlined by Paul in his manifesto ‘Educate, Abdicate, Agitate’. In Paul’s words: ‘Shine a light on the world / expose injustice / help promote understanding / comment on the world around us’.

The Manifesto was designed by Tim Hutchinson

Back to News Page