The ‘Scribbler’, the Photographer and the Celtic Punk

At the end of the 1980s illustrator W. John Hewitt spent two years with photographer Steve Pyke tracking legendary folk-punk group The Pogues. Hewitt reveals how the deep faultlines between photography and reportage drawing actually resulted in unique documentary record.

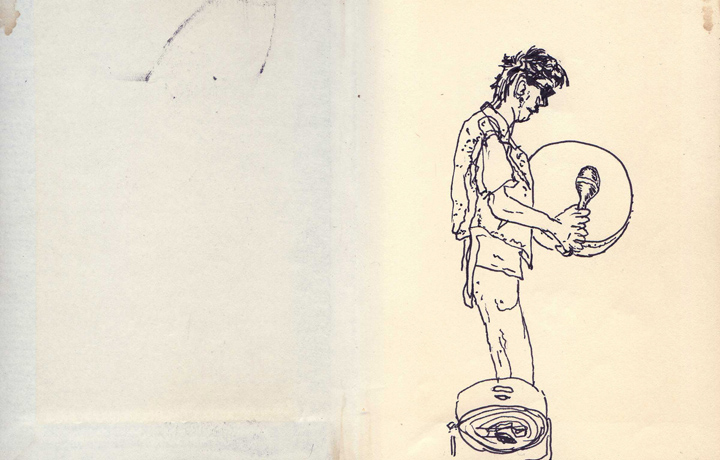

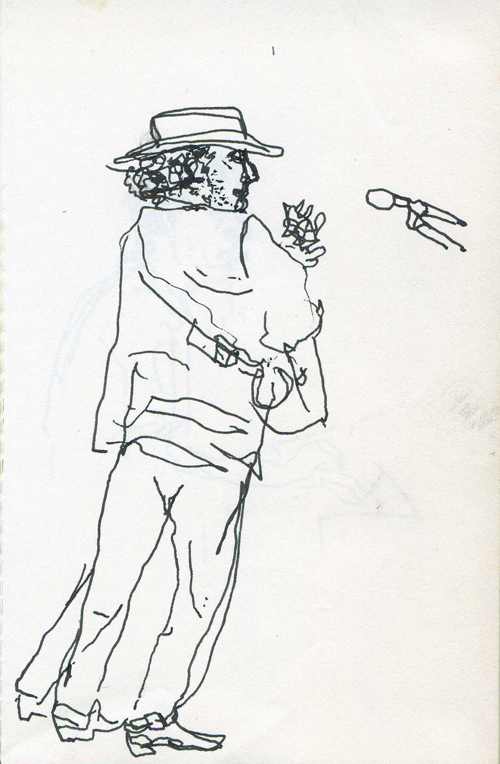

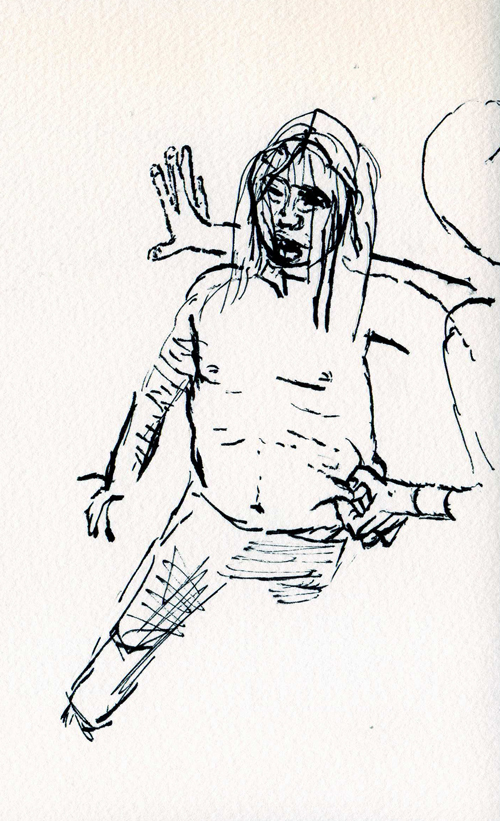

Shane MacGowan performing Cotton Fields, W. John Hewitt, 1988

On a rainy night in Soho, as the song goes, I was drinking in the upstairs bar of the Cambridge, where the only other customers were Shane MacGowan and his rockabilly-styled woman friend. This was in 1981 and Shane’s face was so familiar that it seemed impolite not to speak. I asked something simplistic about his group, The Nips. He said he was forming a Country and Western band, and that was about as far as the conversation went.

Seven years later I was sitting at a table in a fluorescent-bright back room in a cold concert hall in Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent, with six or seven members of the London-Irish folk-punk group, the Pogues (their original name Pogue Mahone is the Anglicisation of an Irish phrase meaning ‘kiss my ass’). Stage manager Charlie MacLennan asked for names to go on the guest list. He met the silence with a gravely response – “No one wants to admit to having friends who live in Hanley,” followed by the group’s fraternal tubercular laugh. Over the previous months I had drawn everyone who was present, and now singer and songwriter Shane MacGowan was leafing through hastily-rendered likenesses in the small sketch pad I had been working in that day. He paused at a drawing of Terry Woods, a veteran of pioneering folk-rock groups of the late 1960s. Sometimes Terry looked like Robert Mitchum in his laconic prime, with curls. The drawing was made during a sound check: Terry was wearing a black suit, Cuban heels and a modest sort of black Stetson hat, giving him the appearance of one of Wyatt Earp’s deputies, brandishing a mandolin instead of a shotgun. The sketch was economically drawn and the face was simply described. “Look,” said Shane, holding up the page to show the others – “Terry’s a cool dude and the rest of us are shitbags.”

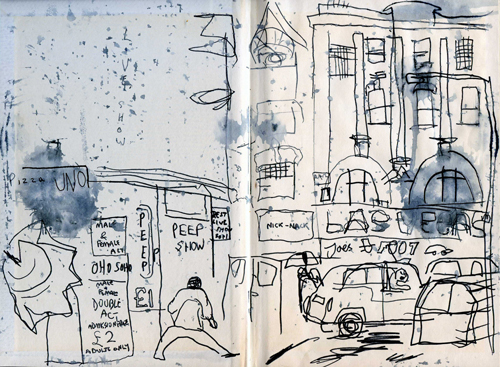

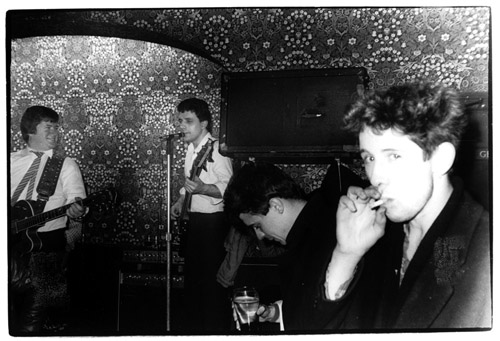

I arrived at this place through years of drinking in particular types of pubs and clubs, which nourished my artwork and brought me into contact with the Pogue’s wider circle. I knew Steve Pyke, who was photographing the group when they were still called Pogue Mahone. I only caught up after hearing their first single, Dark Streets of London. The Pogues stood apart from the Brideshead bands, synthesised soul and rudderless pop of the early 1980s. They rechannelled the energy of punk into songs that were well known by default or from long-denied folkie teenage years. Crucially, Shane’s lyrics gathered frayed cultural strands into an intricate Celtic knot. His words were radical, angry, touching, frequently funny, romantic but never sentimental, and keenly observed. I felt an affinity with the hybrid nature of the Pogues’ music, as a picture-maker who dealt with contemporary narratives but rendered them through ‘traditional’ modes of graphic storytelling. In 1987 the band let me illustrate the sleeve of a single, The Irish Rover, co-recorded with the Dubliners. Part-payment was a trip on the Pogues coach to a festival in Paris.

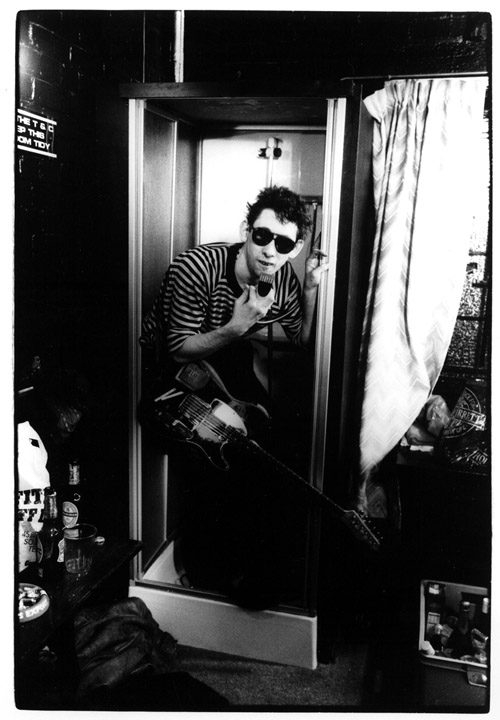

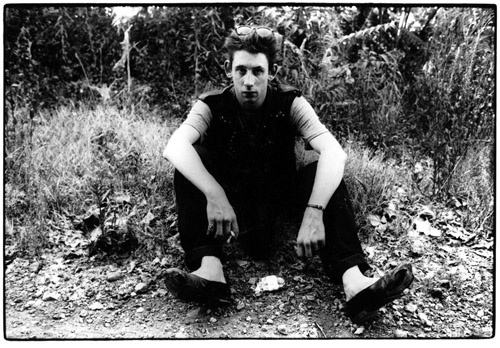

Shane in the dressing room, Town and Country Club, London, 1987, © Steve Pyke

Meanwhile, Steve Pyke and I were thinking of producing a book of drawings and photographs on a common theme. The formula itself was not common, and the effectiveness of words, photographs and drawings interacting on the same page in a single-themed publication was uncertain. We pitched the idea of a visual survey of Thatcher’s Britain, undertaken by following the Pogues’ tour and using the band’s lyrics to underscore the imagery. Faber and Faber were interested but the band’s manager, Frank Murray, reshaped the project as Poguetry: the Lyrics of Shane MacGowan. The only precondition of our access to the band was that we should not depict Shane with a bottle. Frank felt that the media fixated on Shane’s inebriation, and this was his foil.

Shane MacGowan on the bus, W. John Hewitt, 1988

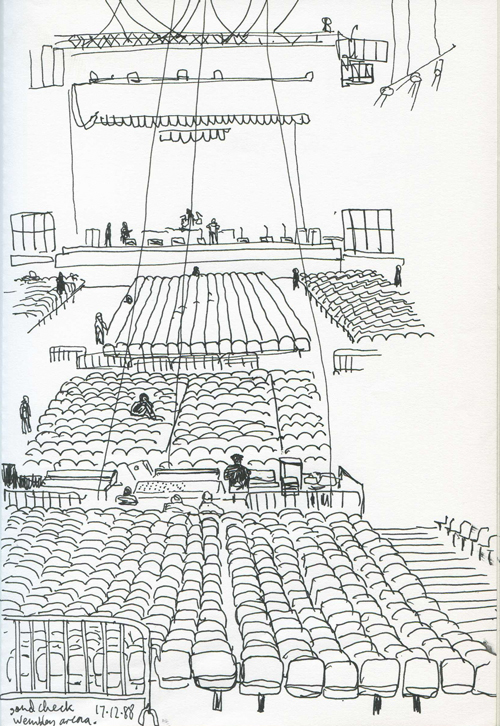

Between 1987 and 1989 I saw the Pogues perform on stage eighteen times in Britain, Europe and the USA, and attended eight recording sessions. Working in tandem with Steve Pyke caused me to reflect on comparative aspects of reportage photography and reportage drawing. It is nowadays rare for drawing to be used as a documentary method in the mass media, beyond lifestyle supplements or visual instructions and signs, though certain comics and graphic journals are beginning to reinvigorate the form. In Britain courtroom artists are the only people who regularly produce drawings as items of daily hard news, and only three full-time practitioners continue in this niche profession. The European tradition of drawn documentary art is as ancient as the depiction of animals on the walls of caves. It is woven into monastic manuscripts and became widespread through the development of print technologies from the fifteenth century onwards. It flourished in news broadsides, single-sheet prints, police gazettes and journals of “useful knowledge.” Newspapers were slow to invest in pictorial content. The Times first printed an illustration in 1806, of Horatio Nelson’s funeral, but when The Observer carried engravings of the coronation of George IV and Queen Caroline, in 1821, sixty-thousand copies were sold and the attraction of pictorial news was confirmed. The comic journal Punch first appeared in 1841, but it was the launch of the Illustrated London News in 1842 that firmly established a ’respectable’ commercial platform for topical illustration. Victorian picture papers were largely dependent on artists who could draw from secondary sources, like the extraordinary Sir John Gilbert who is reputed to have produced thirty-thousand pictures for the Illustrated London News alone. Eyewitness drawing was the domain of ‘Special Artists’ who travelled extensively in pursuit of newsworthy events and would have subscribed to the culture of journalistic integrity that stemmed from John Tyas’s unflinching report of the Peterloo Massacre, published in The Times in 1819. Paul Hogarth, an outstanding reportage artist himself, wrote that a Special Artist, “had to have the intuition of a journalist for knowing what to draw. And he had to know by instinct or design when to be where and to get there in time for it to happen, and once there, to complete his drawings under any circumstances.”

The decline of drawn news imagery has been attributed to the success of photographic and telegraphic technologies in the mid-nineteenth century, but Paul Hogarth identifies a later turning point. When Kodak introduced compact lightweight cameras in 1889, Special Artists used them to take reference pictures. Hogarth’s words read like those of a deflated drawing tutor: “Predictably, they ended up imitating their own photographs.” The power of drawn news was diminished by its best exponents. They chose to replace spatial analysis with flat copying and to elevate the fixed, clipped data of photographic prints over the slippery narratives of memory. “The time had come,” Hogarth wrote, “for the photo-journalist to assume the job.” Joseph Nicephore Niepce had captured the first photographic image in 1826. The medium promised a guileless version of realism but decades passed before photographs could be mass reproduced. The Daily Graphic carried Britain’s first halftone newspaper photograph in 1891 and in 1904 The Daily Mirror became the first newspaper to be illustrated entirely with photographs.

Shane, Mississippi, 1988, © Steve Pyke

Back In Hanley, Shane’s critique of my efforts rang true, at least on the evidence of the pages surrounding the picture of Terry Woods. One sketch showed Shane rattling a maraca against the skin of a bodhran, wearing an expression which was intended to represent concentration but could have been taken for utter gormlessness. He caught the eye of soundman Dave Jordan, across the table. He put the sketchbook down and performed a convincing mime of someone knocking on a door with his left hand, and when the imaginary door was opened he propelled his right fist into the face of the imagined occupier, who, by a tilt of Shane’s head, I understood to be me. Dave nodded, stone-faced.

Steve Pyke was immune from such instant feedback as pre-digital photographs remained enclosed within the film canister until they were developed, but tensions awaited elsewhere. An episode on the road between Dallas and Austin involving me, Steve, the writer Sean O’Hagan, Shane and a bottle of vodka resulted in a backstage inquest at Austin’s Liberty Lunch that nearly had us sent home. On stage the band played for two-and-a-half hours in 100 degrees amid seamless mayhem – fans scrambled over the roof and through windows to join a plunging mob of delirious cow-punks; Shane forgot his words; the electricity failed and nobody cared; women fainted; Spider Stacey puked several times. It was sublime. A couple of days later, near a sweltering Alabama truck stop, Frank Murray caught Steve photographing Shane in the company of a very large bottle, propped in the grass between the singer’s legs. The manager’s yells carried all the way back to the bus – “Is there no such thing as trust?!?”

Shane and Spider, Kilburn, London, 1984, © Steve Pyke

The Alabama picture was published with the bottle painted out, rather badly, leaving its dark ghost nestling in Shane’s shadow. It was trust that enabled such photographs to be taken. While a photograph remained invisible to its subject at the time of its making, the attributes of the photographer were plainly apparent, and Steve Pyke’s open, interested persona chimed with the energies of the band. Furthermore, photographers perform a promotional role in the music industry and the camera is a partner instrument in a band’s relationship with its audience – the medium itself is trusted. Photography is also the ubiquitous method of domestic and social image-making, while drawing, beyond a certain educational level, is not. The cultural familiarity of the lens meant that the taking of photographs might pass without comment, while drawing skills became a subject of curiosity on the Pogues’ tour – and of blunt appraisal.

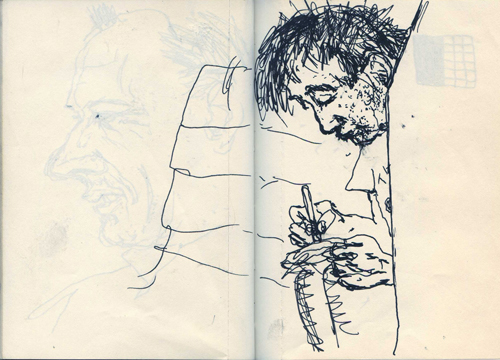

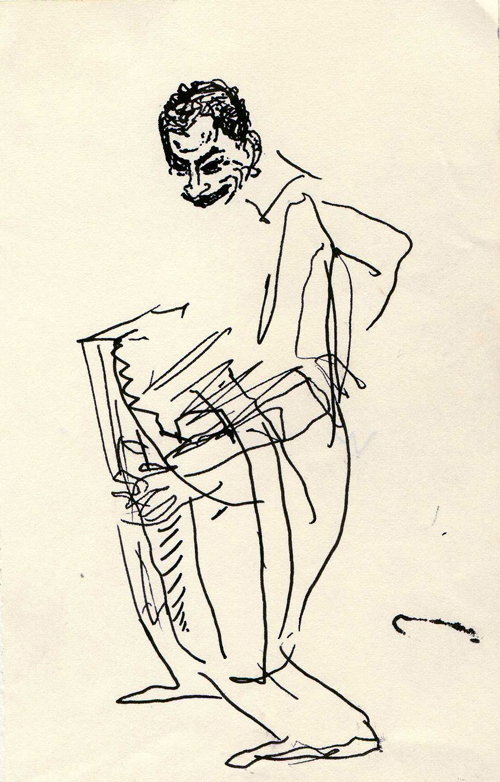

Jmaes Fearnley with his accordion, W. John Hewitt, 1988

The confinement of the tour bus presented opportunities to draw the band in close up without obstructing their work, but long journeys were also rest periods for a team whose nightly commitments were exhausting. I attempted to counter the invasiveness of being drawn by circulating a spare sketchbook, to make the experience of depiction a reciprocal one. Tour manager Joey Cashman claims credit for implanting a tradition of drawing amongst the Pogues, which may account for the ease with which the spare pad was passed around, slowly filling with unflattering images of fellow travellers, captioned to annoy. Shane drew me as a swirling-eyed scarecrow, entitled Hewitt Agonistes. James Fearnley portrayed me as a grinning inebriate under the caption “My favourite weekend”, which I later used as the title of an etching. Shane drew James morphing into his instrument, above the words, “Life accordion to James Fearnley.” Some unkind hand drew Frank Murray as a pound sign, and so it went round.

Most of my tour drawings were done in pocket sketchbooks or A5 pads, using Rotring ‘art pens,’ for their variety in width and weight of line. Facial features were rendered through twists and jabs; postures were often stiff, body parts out of proportion and forms determined by a clogged or flooding nib. As Shane’s response to the Hanley sketchbook testifies, those portrayed continued to perceive a deliberation in any drawn representation, and flawed or roughly rendered marks might be read as commentary while I regarded the unintentional marks as souvenirs of the event of the drawing’s making. To leave a drawing in the state of its immediate production was, for me, an honest record – not of what I had seen but of what I had done in response to what I had seen.

Shane hated being looked at. Even on stage he defied the audience’s gaze with a high-rigged microphone that raised his sightline above the audiences’ heads. Drawing him in close proximity generated tension. Conversely, Shane is a mesmerising performer, so drawing him on stage was energising. Drawing the Pogues in action involved a race between the movement of ink across paper and the movement of people on a stage or dance floor. The contest was un-winnable, and I began to value the function of short-term memory in stalling events until my pen caught up.

This became the essential difference between my approach to documenting the Pogues on tour and Steve Pyke’s approach. Mine was a sequence of anticipation, decision, and fast recourse to memory, while Steve’s activity relied on a period of anticipation before the subject of his decisive moment became immediately fixed in its image form. A photograph is permanently held in its own present, hoarding myriad details and signs for future critical, sociological or personal excavation. As the French philosopher and critic Roland Barthes observes, “the photographic image is full, crammed: no room, nothing can be added to it.” The characteristics of drawing, writes artist Michael Craig-Martin, include “modesty of means, rawness, fragmentation, discontinuity, unfinishedness, and open-endedness.” An eyewitness drawing is additionally a synthesis of scrutiny, emotion and reaction, and – importantly – reflection and memory, be it fast or relaxed. For the photographer, the depicted moment approached – for me it receded; our creative instincts occupied the opposite slopes of a visual pinnacle.

Security at the Liberty Lunch, W. John Hewitt, 1988

Poguetry began as an experiment to test the potential of combining drawings, photographs and words in a published documentary form. In retrospect I harbour a sense of missed opportunities, only partly due to the 360 degrees of sensory choice that location drawing offers. My practice see-sawed between the hesitant and the hurried, and the balance could have been better. Tragically, several vital, vibrant members of the Pogues community died during or shortly after the tours of the late eighties and early nineties. Those who I had drawn included Charlie MacLennan, Dave Jordan, Paul ‘PV’ Verner, Joe Strummer and Kirsty McColl. Their absence brings home the responsibility of depiction and Shane’s Hanley critique nags. My first portrayal of PV – one of the most companiable men I have ever met – was truly awful. Conversely, I enjoy the inevitable unevenness of eyewitness drawing and relish the surprises – good and bad – that arise when skills, materials and circumstances collide. My Pogues drawings succeeded when they were farthest from the imitative qualities of photography and closest to the characteristics of reportage writing – selective, inscriptive, fractured, memory-dependent and made coherent through personal authorship or style. In this respect I can take heart from an early reviewer of Poguetry who referred to my contributions as “scribble drawings.” The Latin root word for scribble is scibere, meaning to write. There is a “graphic and textual nexus,” writes artist and drawing historian Deanna Petherbridge, “within which drawing is implicated but from which it is also separate and autonomous.“

In the mid 1980s my personal store of drawn-reportage influences included Charles Keene’s dryly eccentric Punch sketches, Ronald Searle’s searing prisoner of war drawings, Paul Hogarth’s explorations of Brendan Behan’s New York, Ralph Steadman’s partnering of Hunter S Thompson’s gonzo journalism, Sue Coe’s unsparing visual allegories and Ray Lowry’s documentation of the Clash on tour. These artists’ careers span little more than a century of image making, wedged into the narrowing the tip of an art-historical pyramid. The continuation of their tradition will be dependent on how the values of reportage drawing are measured against documentary photography and writing. Reportage drawing will never be as pervasive, quick, inclusive or ‘realistic’ as photography, but an artist’s ability to interrogate personal memory offers a scopewhich is otherwise only found in literary practices. This form of visual essaying is regulated by the artist’s respect for the experienced event and its depicted participants. It is intensely human; selective, flawed, emotive and dependent on rehearsal and dexterity. It can present itself as a naked trace of the depicted moment or it can be dressed and refined through repeated considerations of a remembered encounter.

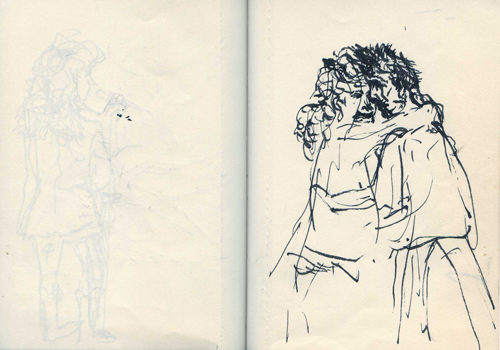

Shane MacGowan and Kirsty McColl performing a Fairytale of New York, W. John Hewitt, 1988

In the years that have elapsed since touring with the Pogues I have become more convinced of the distance between reportage drawing and photography, irrespective of a common subject matter. The deep processes of production in which practitioners are immersed are the source of each medium’s strengths and immense differences. Despite these feelings, I believe the drawings and photographs on the pages of Poguetry did correspond across the connecting bridge of Shane MacGowan’s lyrics. In theory this engagement of visual forms was as doomed as the bickering couple in Shane’s Christmas masterpiece, A Fairytale of New York. Like theirs, the relationship actually worked.

All drawings © W. John Hewitt

All photograps © Steve Pyke www.pyke-eye.com

W. John Hewitt Senior is a lecturer in Illustration with Animation at Manchester Metropolitan University. He is a member of the research network Varoom Lab

Back to News Page