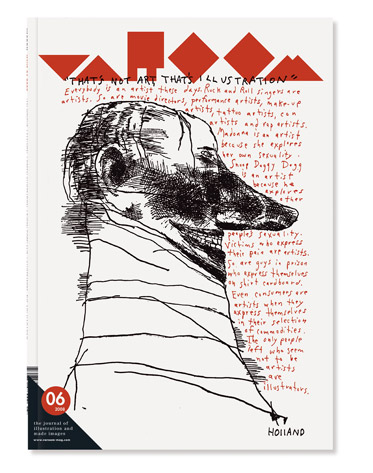

Brad Holland

Jo Davies interviews a major American talent

“I established early on the kind of work I wanted to do. The effect has been that the people who call me now usually want the kind of work I’d be likely to do on my own.”

The use of metaphor within illustration is now commonplace. Many complex, contentious or banal concepts are brought to life through their visual interpretation within editorial contexts where dense pages of text are supported by intelligent sometimes challenging imagery. There are several illustrators, whose work engineered a significant shift in practice, establishing the power of the image as a distinct tool for communicating ideas. Brad Holland must be recognised as one of these pioneers. When he arrived in New York in the 1970’s his approach to creating imagery was radical. The notion that an illustrator was merely an instrument to technically render an art director’s idea was extant.

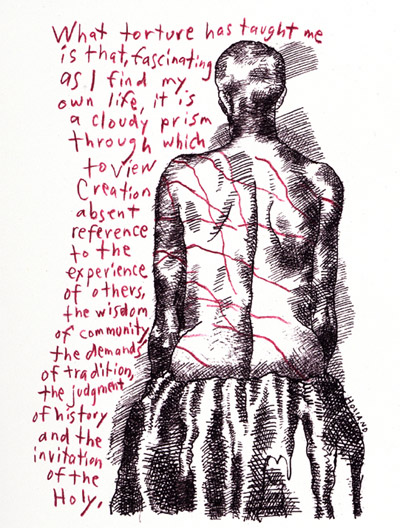

Resilient to the resistance he encountered Brad succeeded in finding avenues for his work contributing a redefinition of the subject and demonstrating the right of the illustrator to retain intellectual autonomy. “One of the things I like about working in print is that you’re always being confronted with new subjects; news events compel you to think about things happening in the world. If you have opinions about life and you’re inclined to express yourself, either in writing or drawing or something else, I don’t see why you should have to channel someone else’s point of view into your work.”

What is distinctive about the approach Brad brings to his work is the specific relationships and function it fulfils in relation to text. Although editors control the content of newspapers and magazines, delegating through art directors to achieve their personal dimension, Brad has steadfastly refused commissions which have diluted his own authorial power as an illustrator. Through establishing this stance early in his career he has attracted clients who have respected this position and been receptive to his conceptual intervention.

“I always work with the text I’ve been assigned but my ideas don’t necessarily come from it. When I first worked with Harrison Salisbury at the New York Times I said ‘imagine you’ve locked the writer in one room and me in another and given us both the same assignment. The writer will give you an article, I’ll give you a picture; you marry the two.’ Their original assumption, that the art should just reinforce the text, was an idea whose time I thought had come and gone.”

Most clients require preliminary drawings before committing to an idea but this can dull the creative process as well as forcing an image to be overly explicit to ensure the editor can access it more immediately. This can impede the evolution that happens during the process of producing artwork.

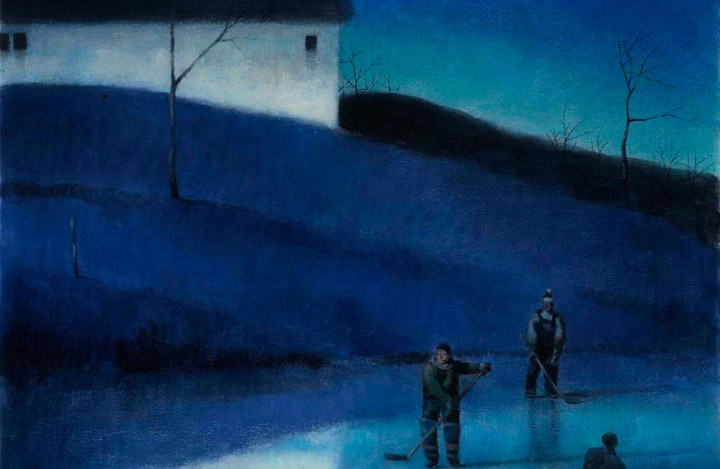

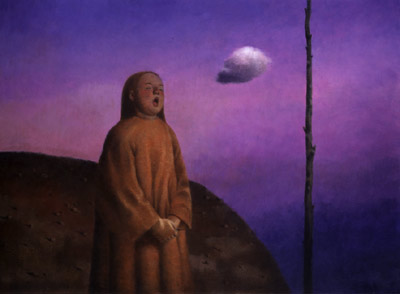

Early in his career Brad drew many visuals for himself building the foundations before starting work on the finished piece. One of the reasons he enjoys working with acrylic is the flexibility and freedom it now affords and because of this he has established a more organic approach, starting a piece and “messing with it” until it becomes right. “When I was young I invested a lot of energy in my preliminary sketches. They were often so completely realised as drawings that when I painted them, the finished pictures were nothing more than coloured drawings. That was fine but coloured drawings just seemed too self-contained for the images I had in my head. They didn’t pack the emotional punch I was looking for. So ever since, whenever I do a sketch, I tend to leave something unresolved about it, something unfinished. That leaves room for the colour to take over where the drawing leaves off.”

He favours the clients who invest complete authority in him to create images unimpeded. In the early stages of his career his was commissioned by Playboy and as he says, “They never knew what they were getting until it arrived each month.” He cites a “perfect” commission to produce a series of 28 images around the theme of fish for a casino. Although specific about the scale of the pieces and deadline the client gave almost complete freedom to exercise creative and intellectual integrity within the project.

It is clear that Brad works for himself and his methodologies are similar to those painters who may be classified as fine artists. Early in his career he was repeatedly told, despite his immediate and repeated success, that he was un-commercial. In common with many fine artists he has always been entrepreneurial finding avenues for his ideas. “My idea is to come up with the work I want to do and then find the market for it. I’ve never seen the virtue of finding what the market wants and then trying to supply it. The market doesn’t know what it wants. Art isn’t a commodity. It’s the result of a vision and vision has to start with an artist.”

For this reason he considers the definition and labelling of illustrators a constricted one. He admires Graham Greene, a literary polymath, who worked fluidly within a broad literary field unfettered by boundaries. He says of his own beginnings as a ‘commercial’ artist’, “I’d rather be a fugitive than have art directors tie me down to one thing. I’ve always assumed my voice would have many octaves. The business was constrained by style but I was always happiest being un-caged.”

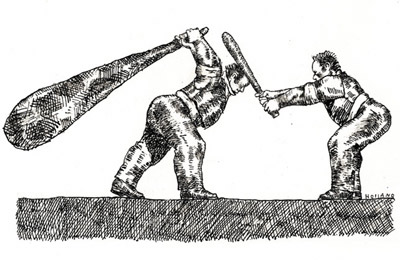

Anchored by a prodigious ability to draw and to think, Brad has been open and varied in his use of media, cross hatching with pen and ink, gritty pastel drawings as well as acrylic paintings. Of the fluctuating styles in the illustration markets which have punctuated the decades of his career he says, “I’ve never kept up with trends. If I notice a trend, my inclination is to go in the opposite direction.”

He has over the course of time been prolific both attracting and declining high profile clients internationally across a spectrum of areas beyond editorial work. His visual language has been appropriated and a rash of ‘Brad Holland clones’ have yielded their clichés. Ubiquitously some are prepared to be the conduit for an art directors idea where Brad has consistently refused. Few if any of these imitators exercise the sincerity of intention of the original. He is clear that commercial practices don’t impede or compromise his vision.

“I love the work I do. Since I was 17 I’ve been paid to do pictures I’d have done anyway. I hate deadlines but I find them useful. They concentrate your attention. They force you not to dither. You don’t always do your best work under pressure, but you can always do your best to do your best. And – if a picture needs to be reworked later, you can always do that too.”

Brad recalls the incident of a client who wanted to commission illustrations for an advertising campaign. When Brad refused to ‘render’ the art director’s ideas he was offered a challenge. A Brad Holland ‘imitator’ was brought in to fulfil the brief as originally proposed. Brad was given carte blanche to interpret the brief according to his own concepts. The client was given the ultimate choice. Brad’s work was chosen.

He developed an external attitude to himself when he was a child, an outside persona who he called upon for judgement. He called this “thirty-year-old Brad” and recalls, “I always needed someone I could turn to for advice, but there was nobody around my little town I could count on. So I made somebody up. I tried to imagine myself as a thirty year old. That seemed to do the trick. I’d always ask myself if the things that mattered to me as a teenager would matter when I was 30. As a rule the answer was no. So thirty-year-old Brad kept his eye on the horizon while I navigated the bumps in the road. Then, after I turned thirty, I realised that that state of mind would be as useful leaving thirty as it had been approaching it.”

The bumps in the road, recently, threaten the journeys of all illustrators and Brad has devoted substantial energy to fighting the changes to copyright which challenge ownership of intellectual property, undermining the fee structure for the entire profession. This crusade seems a natural extension of the work of a man who has operated within a political arena and demonstrated the value of imagery to pack a punch.

Brad Holland was born in Michigan USA and has lived and worked in New York since 1967 He has won more awards presented by the New York Society of Illustrators than any other illustrator in its history. In 2005 he was elected to the NYSI Hall of Fame. He has been described as, “the most important illustrator in American today.”

Jo Davies is an illustrator and writer, co-author of Making Great Illustration A&C BLack, and Associate Professor of Illustration at Plymouth University

Back to News Page