The Kandahar Journal.

Richard Johnson is the Graphics Editor at Canada’s national newspaper – the National Post. With a background in illustration and journalism, Johnson has taken his data visualization and visual reportage skills around the globe. As a filmmaker and photographer with the United Nations, Johnson documented rape victim recovery programs in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, refugees in Zimbabwe, and IDPs in the Central African Republic and Kenya. As a foreign correspondent and war artist, Johnson has embedded with various armed forces in Iraq and Afghanistan, and with peacekeepers in Africa. He uses his illustrations from the field as a device to make people read his first person narrative stories on day-to-day life on the front lines. Richard’s reportage work was also previously featured in Varoom 16.

Friday, Aug. 17, 2012.

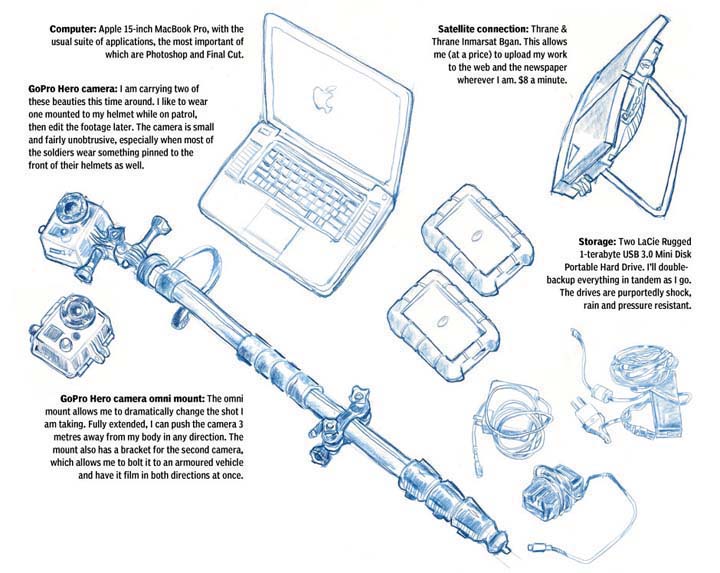

I have two rules when it comes to embedding with the military in a war zone: 1, I have to be entirely self-sufficient (the worst impression you can give soldiers is that you are needy or a liability); and 2, I have to be able physically to carry all my gear for a reasonable distance (soldiers have enough to worry about without some office jockey needing help to lift his bags).

The other day I sat in my basement surrounded by a mass of equipment, desperately trying to cut down the weight. It struck me I am packing a lot of necessary stuff; then it struck me people would not believe how much stuff I am trying to squeeze in and carry. All the gear packed up (below).

This week, I head back to Afghanistan to spend time with International Security Assistance Force Troops. I’ll be spending a little time in and around Kandahar City with the U.S. force that took over from the Canadians when they left last year. I’ll also be with the almost 1,000 Canadians who remain in country, training Afghan personnel.

Tuesday, Sept. 4, 2012.

Combat Outpost (COP) Mizan, Zabul Province, Southern Afghanistan. COP Mizan is a base around 80 km away from Qalat City in Zabul Province. There was a point a few years ago, when Mizan and it’s surrounding valley and villages were considered a success for ISAF and relatively safe. The Taliban seemed to have been driven out. However a Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) program to eradicate the poppies farmed there along with a resurgence in Taliban attacks and use of Improvised Explosive Devices (IED) on the only road route into the valley has effectively nullified any progress made.

COP Mizan and its surrounding outposts (OP) come under some kind of an assault more or less nightly. As I sit writing this blog there is a steady boom of outgoing mortars from the Afghan National Army base in response to an attack on a nearby OP. The COP itself sits in a valley and feels extremely exposed.

The Security Forces Assistance Team (SFAT) unit I am with are all business when it comes to soldiering. The card playing jokers of the night before are nowhere to be seen when we roll out in our three Mine Resistant Ambush Protected All Terrain Vehicle (M-ATV)s to join the convoy of vehicles heading for Combat Outpost (COP) Mizan. The convoy contains more than a dozen vehicles all tucked in behind a specialized route clearance team of 883rd Engineers.

Before we mount up 1st Lt. Eric Redless and SFC Kevin Patton give me the run down on entering and exiting the vehicle in case of a rollover. They show me how to combat lock the door and how to use and release the five point harness that will hold me in tight. They have also stuffed my pockets with quick clot bandages and a couple of tourniquet. Inside the vehicle wrapped in body armour, helmet, ballistic goggles, gloves, and a blissful euphoria – I wonder what the hell I am doing? There is, at least, a small triangular window – so I can see out through the 3cm thick glass and the ‘bird cage’ of anti-rocket propelled grenade (RPG) armour to the desert beyond. Joy.

I can just about see the helmet of 1st Lt. Redless the driver in front of me and if I lean forward and put my head against the back of his headrest I can see Major Nathan Whitlock in the passenger seat (left). If I turn my head to the right, I would be able to see Sgt. Kevin Patton if it wasn’t for the ass-end of 1st Lt. John Fellows in the combat sling of the M-240 gun turret above. I have had more legroom and elbow room on an Air Transat flight, but not much more. I make sure my water is within reach.

We finally get underway after a bit of a stall to pick up interpreters for the various units heading out. After clearing Qalat we head out into the desert on hard top. It even has a line in the middle of the road – a rarity in Southern Afghanistan because people keep stealing them. It is such a smooth ride and the convoy speed so slow that I decide to attempt to draw on the move. Not quite smooth enough to allow me complete control, but not bad considering I am wearing gloves and dealing with the odd weave.

About half way to COP Mizan we pull off to the side of the road to test fire the weapons system. I get to try my hand on the M-240. I aim at something fairly large – a mountain – and nailed it. There is no kick because it is mounted to the vehicle, and the urge – even for a guy who has never even held a gun – to just keep pulling on the trigger is almost overwhelming. I yield after a few bursts. I learn my lesson when I grab a shell casing as a keepsake on the way down.

Back in my seat and immersed in claustrophobia once more we roll off the end of the hard top. When we hit the talcum powder sand of the Afghan land, suddenly we can barely see the silhouette of the truck in front as it heads into the soon to be setting sun.

The contract to create a hard top road out to COP Mizan is a subject of some controversy. It seems that a number of different contractors have taken on the project at various times, only to be dissuaded by either the engineering challenges of the rolling undulating terrain, or the Taliban. After getting paid of course.

The route clearance team have been working the remaining stretch of 25 km to COP Mizan for most of the day, so the road ahead should be clear. Unfortunately when the dust kicks up high enough it can be very hard for Lt. Redless to see the vehicle ahead of him. In places the dust is knee deep. Perfect terrain to hide an IED.

Minutes later we get word that one of the route clearing vehicles had struck one. The convoy grinds to a halt in the darkness. I can now look out my window and see myself looking back. While Major Whitlock sorts out what is going to happen next, through rank, will power and harsh language I lean my head on the headrest in front and sketch him in full consternation.

It doesn’t take long to tow the vehicle clear and get us underway. There were no casualties in the blast. The Route Clearance trucks are seriously built. Still I have to wonder at the soldiers who end up in that job and thank them for their bravery. We almost drive into the blackened oil filled hole left by the IED and have to back up and go around.

When we roll into COP Mizan I am exhausted and yet I have done nothing at all for the last five hours. I think about my promise to try and blog every day and decide to smoke a cigarette and go to sleep instead.

The SFAT guys had been nice enough to bring me a cot so I had slept well enough. I woke up staring at the underside of the M-ATV and the charcoal coloured hills beyond. Seeing the ocean of sleeping bags around me I got up and went and took some photographs of the sleeping soldiers in the morning light with the smoke from the garbage fire blowing through. Artistically this was far from ‘Constable’ country.

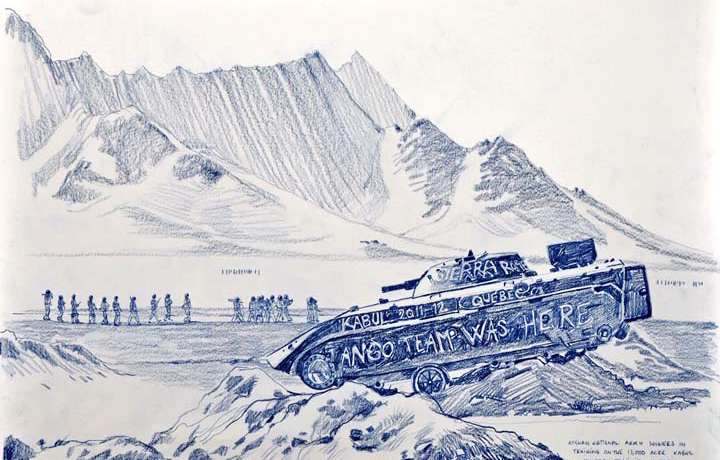

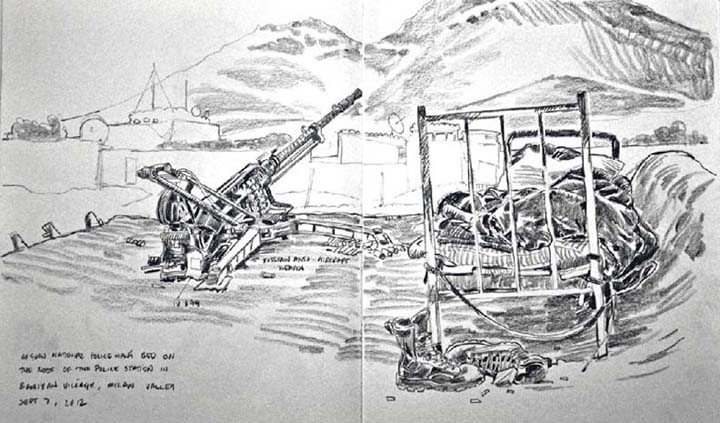

But still I am here to capture the conflict in pencil so I took my sketchpad, begged my way onto the roof of the Command Post and put pencil to paper. COP MIzan is not pretty to look at (above) but it is home for the next week.

The bed of an Afghan National Policeman on the road of the police station in Bamiyan Village, Mizan Valley, September 7, 2012.

Thursday, Sept. 13, 2012.

Kandahar Air Field (KAF), Kandahar Province, Afghanistan. I am sitting in a small corner of shade on the edge of the runway at KAF. My flight has been pushed to the right once already this morning.

Four days ago I began a seemingly never-ending travel odyssey with a ride down from the budding Tur-Muryani strongpoint, which will — when complete — overlook Mizan Valley in Zabul Province. I shook the hands of the U.S. Security Force Assistance Team (SFAT) 42 members, who are be stuck up there for at least a week more. “It was great, guys. Thanks.”

Somehow Sgt. Patton kept us in the dust as huge boulders on either side of the “road’ whipped by at ever-increasing speeds. We hit the flat at the bottom doing 60 km/h, somehow held onto the gravel beneath enough to make a fork in the road, and slowed to a not particularly graceful halt. Sgt. Patton had either almost killed me or just saved my life.

I rode the rest of the way out along the road – it had been registered ‘black,’ meaning nothing like secure – standing up in the back of the Gator, filming with a helmet Camera. The road was now under constant over watch, but in the moon-dust-like sand it takes only seconds for someone to place an Improvised Explosive Device (IED).

I had enough time to get cleaned up, feel thoroughly refreshed and grab some food before I found myself sitting on the gravel Helicopter Landing Zone waiting on a scheduled ride out. Almost four hours later, sweating, sunburned and smelly again I realized that no helicopter was coming.

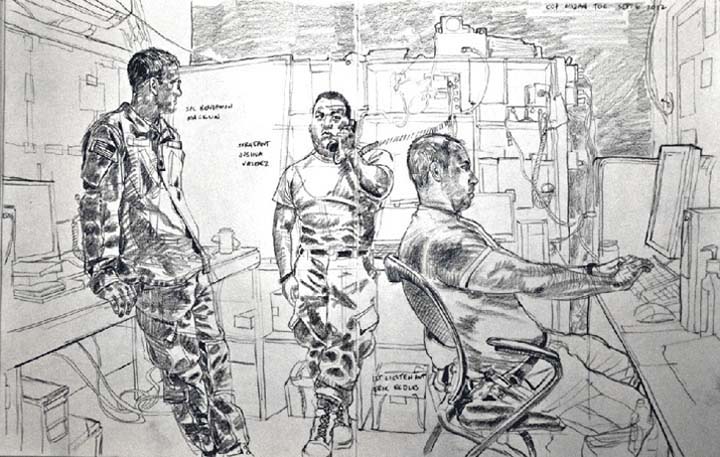

I spent the evening in the Tactical Operations Centre killing time and sketching while a variety of U.S. soldiers coordinated a mortar team in support of the guys on Tur-Muriyani hill (below).

Everything happens for a reason – I guess. The next morning – thanks to my delay – I attended a shura of local villagers organized and led by Afghan National Army Colonel Altafullah of the 6th Kandak. It was an opportunity for him to smooth the ruffled feathers of the purported civilians who were now trapped in a ‘no man’s land’ between the ANA on Tur-Muryani and the Taliban on the other side of the Arghandab River Valley.

The all-male crowd contained a large number of fighting age men – something that had been missing on my patrols through the villages in the Valley. The meeting took place under the large spreading branches of a tree in the courtyard of the local Afghan Uniform Police (AUP). About 100 almost entirely bearded men waited for to Colonel Altafullah talk.

Friday, Sept. 21, 2012

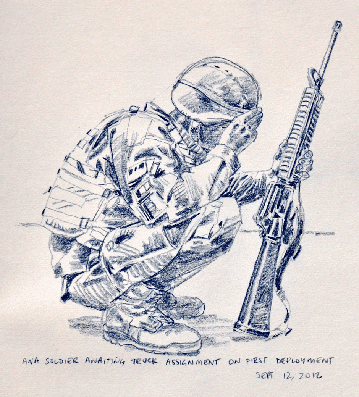

Kabul Military Training Centre, Kabul Province, Afghanistan – Sept. 15, 2012. Yesterday, U.S. ISAF troops were ambushed near Mizan in Zabul Province while they were responding to a call for assistance from local Afghan Uniform Police. Four were killed.

Two days ago a man in a police uniform killed two U.K. ISAF soldiers, when they went to assist someone in need of medical help. These deaths bring to 51 the number of NATO troops killed in such attacks this year. For Canadians operating inside the wire it is no longer safe to assume you are safe. The threat now is an enemy hiding in plain sight.

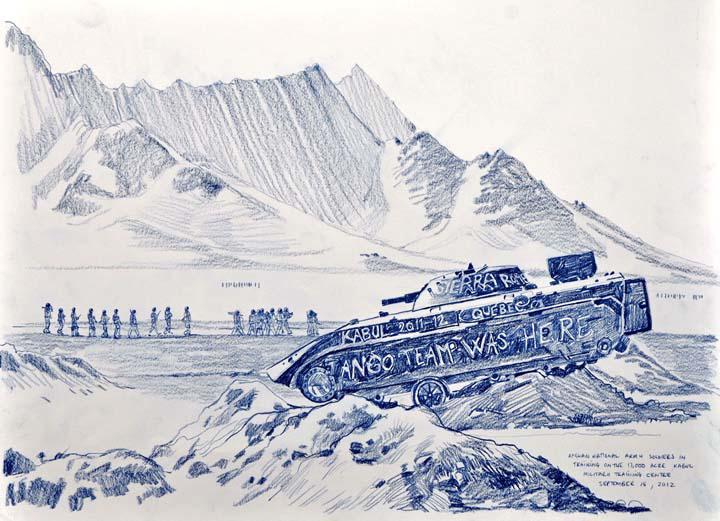

The sheer scale of the Afghan base makes it feel that we are outside the wire. The illusion is tough to shake on the dusty gravel road as we pass by weapons ranges and the odd abandoned Russian vehicle, rusting very slowly in the high dry Afghan air. Long ago stripped of everything useful, the vehicle wrecks date back to when the Mujahideen fought the Soviet Union to a standstill in these valleys and peaks just north of Kabul.

The Canadian soldiers I am with are all business no matter how short the excursion. They stay in regular radio contact with Blackhorse, and always have someone playing guardian angel when we are out of the vehicle. The “guardian angel” program has someone with a loaded weapon nearby, but uninvolved, when meetings between ISAF and the ANA take place.

We eventually arrived at an ANA firing range where we were hoping to find some Canucks busily assisting. The Canadians we were hoping to find mentoring, though, were nowhere to be seen. (I found out later that they had blown an axle on the gravel road and had returned to Blackhorse). The brand new ANA troops were working or registering their newly acquired weapons. Shooting at targets and seeing where the shots actually hit and then adjusting the sights to make up for deviance in any direction.

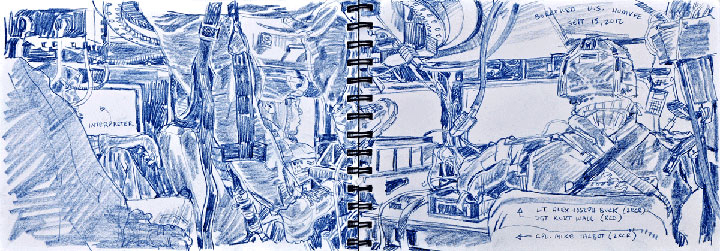

I took the opportunity to get some footage, hoping to hook up with the Canadian mentors at a later date and somehow piece the story together from there. My “angel” for this stop was Corporal Mike Talbot. But back in the turret of the Humvee (above), Sergeant Kurt Wall had the M-240 machine gun on overwatch.

In what I assume is standard firing-range procedure in an army, no ammunition was handed out until the soldiers were ready to shoot. And everyone shot until the magazine was dry. I got out the cameras and the video cameras and did what I had to do. I worked with the hair standing up on the back of my neck (The next day a further security measure was announced. No more attending ANA live fire drills for Canadian mentors).

With our failure to find any mentors at the firing range, we bounced back immediately and headed for the operational training grounds, where we hoped to find some ANA Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) working alongside their Canadian mentors.

En route we drove past another Soviet personnel carrier-turned-Afghan sculpture (above). Some wag from a previous rotation had scrawled “Tango Team Was Here – Quebec” in white spray paint on its side. “Make a right here” Lt. Alex Buck said.

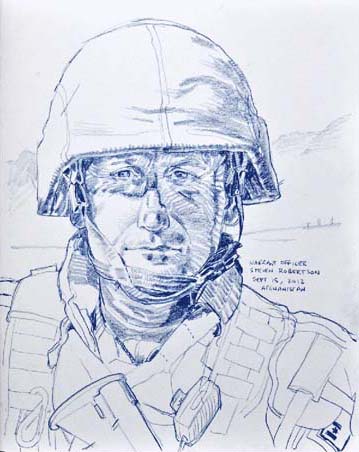

We found Warrant Officer Steven Robertson (left) shouting at a group of forty ANA NCOs squatting on the ground. The NCOs are part of a training program that brings in experienced soldiers from the field and turns them into leaders. It teaches things like how to conduct yourself to maintain respect of your troops, and how to make sure the soldiers under your command are ready for battle. The kind of basic soldiers skills that the Canadian military would more or less take for granted at home.

WO Steven Robertson, the sole Canadian in the group, was busy educating them. “Respect your soldiers. You need to ensure that the soldier is first, all right? I am not here talking for the good of my health. I want you to learn this and understand it.” he shouted.

His fervour was somewhat tempered by having to stop to let the interpreter translate in a less emphatic style. He walked back and forth through the seated figures during each pause. “I saw an episode today in which a young sergeant didn’t know how to discipline his troops. It is YOUR responsibility as NCOs to make sure the proper amount of discipline is given to the troops … make sure your troops do the right thing … They will respect you.”

Part of the drill today had been clarifying proper positioning of troops to secure an area and avoid an ambush. “Soldiers were put in the wrong positions, and even when I corrected them some of the NCOs didn’t know where to put them. The NCO should look at any piece of ground and know where the best place is to put soldier, for best effect and the safety of the soldier. Today the NCOs were not being NCOs. They were basically being lazy,” he said.

He clearly had the attention of the NCOs squatting on the ground now. Even via the translator he seems to be getting his message through. Eventually though, he hands over the remonstration to an ANA sergeant, who is the actual instructor. The ANA Sergeant seems to take a page from WO Robertson’s guidance manual as he works himself up into a frenzy, over their mostly bowed heads for the next 10 minutes.

“Soldiers are soldiers, once you train them they will know their job. The problem is getting good training in a good time period. We are trying to instill as much as we possibly can. But in the end it has to be an Afghan led training team to build an Afghan Army. That is my feeling on it,” said WO Robertson.

Wednesday, Sept. 26, 2012

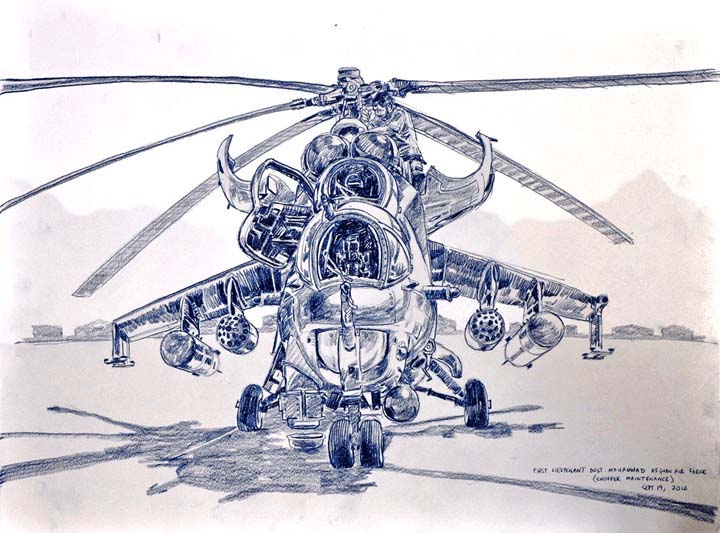

The Afghan Air Force (AAF) MI-35 Hind helicopter gunship sits squatting on the runway in the noonday Kabul International Airport (KAIA) heat. Even with its innards exposed, the Hind still looks threatening. It looks just like the Apache doesn’t. While the Apache looks like a toy, the Hind – even this 30-year-old bird – looks like the grown-up real-deal. It looks like it could take a “young boy’s wish” and crush it. The look is all illusion though. This Hind is a legacy vehicle of the AAF. It somehow survived the fall of the Soviet Union, the resulting civil war, the abuse and abandonment of the Taliban, and the aerial bombardment by the U.S. in response to 9/11.

The man under the cowling of the Hind is First Lt. Dost Mohammad. He has been a maintenance mechanic with the AAF for more than two decades. He is legacy staff — meaning — old school, intelligent, careful and loyal. Exactly the kind of people you want maintaining your Air Force. He has seen it all in his time.

“This chopper has two engines. In one situation, we had an engine failure. On one engine you have to land quickly. We had to throw things of the vehicle to reduce weight. We dropped the fuel tanks and weapons and threw the baggage out the door, we landed hard – I felt lucky to still be in this world,” said Lt. Mohammad.

This Hind has spent the last decade mothballed, intended for scrap. But with the withdrawal of the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and its handy blanket of air cover planned for 2014, a program of refurbishment is pulling this one and two others like her back from the brink. “Her name is ‘Tiger’ because of the camouflage striping,” Lt. Mohammad said.

Eleven Canadians work alongside the officers of the AAF at KAIA as part of a 35 strong, 738th Air Expeditionary Squadron (AES) their mission is to “empower the AAF Airmen to achieve operational success through education, leadership development and professional training,” according to the fact sheet. They are here to help advise, guide and develop the Afghan Air University (AAU). So far they have graduated around 4,000 airmen and installed more than 50 new instructors.

1st Lt. Mohammad is exactly the kind of airman that they hope to create. The challenge though is finding the raw material of a suitable caliber to fill their university openings and then the Air Force trades and occupations. For now their only stream of new recruits comes from the Afghan National Army, which – with illiteracy and innumeracy rates as high as 90% in new recruits – has a vested interest in keeping the best and the brightest to itself.

“There are politics in everything that happens here. We are supposed to have first pick (of personnel) in certain Kandaks in development. But when we get out there we notice that the Kandak is much smaller than it is supposed to be — there are a bunch of people missing — the Kandak has already been picked through. At other times, the ANA will just have extra (soldiers) in infantry training, and they will say, ‘Hey, air force, they are yours now,’ then we have to figure out what to do with these guys,” Said Lieutenant Colonel Walter Norquay, the Canadian Chief of Staff for the 738th AES and the Afghan Air University. He is from Cole Harbor, Nova Scotia.

The challenge of student literacy is doubly complicated when it comes to creating airmen. Many of the key aircraft documents and manuals are only in English to avoid any loss in translation, and additionally the official International Civil Aviation Organization language is English

“They have to be literate in their own language, and if they have English language proficiency, they are signed up to be aircrew right away. We put them through some testing. They may not be a pilot, but they might be a flight engineer,” said Lt. Col. Norquay.

The AAU has almost 400 students studying to become airmen, supported by 31 AAF qualified instructors. The birth of what will hopefully become a fully independent AAF in the future.

A Canadian, Lt. (Navy) Jan Downing (left) from Newfoundland, is the Aviation Medicine Advisor at the AAU. She is here to help build a sustainable program of Flight Surgeon qualification. A flight surgeon is a doctor specifically trained in the aspects of flight-induced medical problems. A flight surgeon makes sure that sick people are not flying or supporting the flight of aircraft.

“We [738th AES] along with the Afghan Surgeon General created and ran a course. We think it was a success, and we qualified six doctors as flight surgeons. And we’d like to qualify as many as we can so that in each big Air Wing they can do a flight physical or have that little bit more expertise. The continuing challenge is going to be Afghan involvement in the teaching part over the next few years. We have to leave someone to continue the teaching, ” she said.

This is Lt. (N) Downing’s second tour in Afghanistan.She previously spent two months in Kandahar Airfield at the Role 1 clinic in 2010. She volunteered to come back as an advisor on this deployment. “I got my taste down there, and I have always liked teaching. They (Canadian Forces) spotted my flight surgeon qualification when I volunteered and directed me here. . It is a cliché I know but, I am very lucky to be Canadian and live in the country that I do. I think serving for your country is an honor. It is very rewarding and very fulfilling,” she said.

The Afghan Air Force has been around in one form or another for almost as long as the Canadian Air Force. It was formed in the 1920s with help from the Brits and the Soviets. In the 1950s and 1960s it was the dominant Air Force in the region. But many of the pilots and technicians available today are the ones trained by the Soviets in the 1980s. A great deal of the important knowledge still rests with these AAF personnel.

Leaving Afghanistan turned out to be almost as hard as getting in. I arrived three hours early for my flight out of Kabul back to Dubai, only to find that it had flown out two hours earlier than that. Sheesh. So I got an extra night at Kabul International – thanks to Major ‘Art’ Brown of the Canadian Air Force for taking me in on zero notice. I made another flight the next morning at 4.30 a.m. and ended up back in Kandahar, I was so sure I would never be here again. Last view out the window as I headed for Dubai was of the original 1960’s Kandahar Airport terminal building now surrounded by 4 km of ISAF base in all directions. Another hop got me to Dubai where I killed ten hours in the terminal. At some point during the transfer of luggage, Dubai customs held one of my bags because of explosives residue (I blame Special Forces Operator MCpl White for letting me wrap a cake of C4 explosive in detonating cord, while I was ‘helping’ with a late night ordnance disposal, and poor hand washing habits. One more flight to Zurich, one more flight to Newark in the U.S., one more flight into Toronto, and one taxi ride home – and I was standing at my front door with 50% of my luggage. Only 43 hours after I set out.

Inside I could hear my kids running around and laughing. It felt very good to be home.

As the clock ticks toward the deadline to 2014 when the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) coalition will depart for home, there is an anxiety for people in the villages and the cities of Afghanistan. It is an uncertain, wait-and-see.

But I think, for the Taliban, the announcement of an end date has directed their focus. For now they are waiting patiently, doing what they can to prepare the ground for the moments after ISAF has gone; adopting tactics to sow dissent and distrust of the ruling government among the populace, while also nurturing an environment of distrust between Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) and ISAF.

By the targeting of ISAF by IEDs they use the international force’s own casualty-averse, risk-averse stance against them. When an attack occurs movement is restricted and convoys don’t roll. Stopping them from working alongside and mentoring the ANSF they are supposedly trying to help.

Add to this, the rising tide of inside-the-wire attacks, and even the simplest training endeavors become a seeming potentially deadly mission, a real-life game of Russian Roulette. The ISAF response is to increase security further, again distancing themselves from the people they are trying to help.

My time in Zabul Province gave me an example of how effective the Taliban tactics are; a Security Force Assistance Team (SFAT) 42 out of Camp Apache near Qalat City had been providing mentoring and support to the Afghan National Army’s 6th Kandak. The 6th Kandak’s mission was to wrest control from the Taliban of a key logistics route along the Arghandab Valley. A single road led from the city of Qalat into the Mizan Valley and then on down to the Arghandab River.

The mission was seemingly successful with the 6th Kandak rousting of the Taliban from the Mizan Valley with SFAT 42 doing nothing more than providing advice and air support when required. A perfect example of coordination while gradually ceding control to the Afghan Army.

But on the road into Mizan, three ISAF convoys detonated four IEDs, all less than 100 metres from an Afghan National Police (ANP) checkpoint. None of the ANA convoys struck an IED. And then two days later a so-called ‘green on blue’ attack in the Mizan Valley left four U.S. soldiers and an ANP dead. Five other ANP strangely went missing.The SFAT team and its ISAF support units were pulled back to their home bases by their commanding officers, and any opportunity for gain in trust and learning through the SFAT program of mentoring was lost with the withdrawal.“The enemy again knows exactly what to do to get what he wants. This means we won’t be able to complete the mission. It is like they have a crystal ball or something,” said SFAT 42 Commander U.S. Major Nathan Whitlock.

Tens of thousands of trustworthy ANSF working alongside ISAF personnel are now forced into the indignity of being treated as an enemy, kept at gun’s length. The Western forces this summer adopted what they call a “guardian angel” policy, in which one member of each ISAF force stands armed, locked and loaded, overseeing interactions between troops and their Afghan allies. Not exactly building blocks of trust and learning.

“I pat down every ANA who comes through the gate regardless of rank, regardless of whether they like it or not,” said U.S. Specialist Thomas Wood, on guard at the gate between Camp Apache and the adjoining, much larger Afghan National Army Camp Eagle.

So for minimal use of their precious resources and small risk to key personnel the Taliban gets maximum impact, maximum distrust while they wait for ISAF to leave.

Canada still has almost 1,000 soldiers in Afghanistan involved in Operation Attention, Canada’s part in the NATO mission to deliver training and support to the ANSF. Most Canadians are based in Kabul and serve with Training Advisory Groups assigned to the Afghan National Army, Afghan Air Force and Afghan National Police, helping with leadership training, instructor development and curriculum. There is also a Medical Science Advisory Team of 40 doctors, dentists and surgeons spread between the Kabul Armed Forces Academy of Medical Sciences and the Mazar-e-Sharif Medical Hospital within the Regional Military Training Centre there.

Ask any Canadian working in Afghanistan as part of Operation Attention – on the record – how things are going, and they’ll reflect on the positive. You will hear how deadlines are being met, targets surpassed, quality improved, and goals achieved despite multiple challenges. It is all true – the work being accomplished by the small number of dedicated professionals and support staff that we have on the ground seems like a biblical miracle.

Turn the microphone off, and the sentiment shifts. Talk to anyone outside of headquarters elements — people in direct contact with the same surpassed targets, achieved goals, and multitude of challenges – and they will talk – regardless of rank – of an underlying feeling of unease about the future for Afghans.

“When we leave, I am worried for them. I am worried that someone else will take over or that some of the ANA will turn, but I am hoping that the work we are doing will counter that, and I hope that we are training ethical leaders who will remain patriotic for Afghanistan instead of for themselves,” said Canadian Lt. Alex J. Buck.

On the eastern edge of Kabul stands Camp Blackhorse, a base within Kabul Military Training Centre. In the mountains, warehouses, classrooms and offices here Canadians mentor Afghan instructors as they spend nine weeks forming, equipping and training ANA Kandaks. The completed Kandaks – as many as 500-men strong – roll out in the middle of the night aboard convoys of 150 brand-new vehicles to their assigned ANA Corps location. Sometimes three Kandaks will roll out at the same time. Between June of 2011 and October 2012, 70 Kandaks have rolled through the front gates.

Successful as the Canadians have been in this process, many Canadian mentors say they have distinct misgivings about the production-line method of creating entire units of rookie soldiers, officers and noncommissioned officers, many without even the most rudimentary literacy or numeracy.

“Back home – during training – they won’t pass you if you don’t meet the standard. They won’t deploy you if they think you are going to die because you are not mentally trained and ready. Meanwhile here, that is what we are doing. We are deploying units that … are not to a standard where we would like,” said Canadian Major Alinah Cruz

The largest percentage of Canadians here are working to help train the Afghan National Army, with a goal of building a 187,000-man force by October 2012. They are helping the ANA build a sort of military training university – one that can churn out soldiers capable of reading maps and basic manuals. It’s not exactly West Point, but it’s hoped that it will continue to improve and to operate long after the Western forces have gone. For now though they have to work with what they have.

“For the most part all of the [ANA] officers are literate, but for the [ANA] NCOs only a few are literate – to a degree. Their literacy is higher though than the soldiers they are training,” said Lt. Alex J. Buck.

Another task for ISAF is teaching basic logistics – that is the planning and systems required to get bullets, food and bandages to the frontline but also the necessary materials to enable them to save lives and treat the wounded.

In the center of Kabul, the Canadian Medical team at the Armed Forces Academy of Medical Sciences must limit what they do. They are in place to create a system of learning that will continue after 2014 to produce excellent military physicians. The task here is to mentor, not to lead. Canadian Military doctors may find themselves having to stand back and let patients suffer while Afghan Military Doctors consider the symptoms and make their own diagnoses.

“They have real problems with procurement, even for simple problems like getting IV nutrition, storing it properly, keeping it in stock. This is a problem they have had for a long time.” Said Canadian General Surgeon, LCol Vincent Trottier.

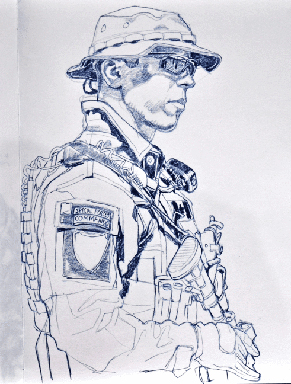

South of Kabul, Camp Morehead is a small ISAF base within the considerably larger Camp Commando Afghan National Army Special Operations Command base. It is here that members of the Canadian Special Operation Regiment are mentoring ANA trainers in the creation of ANA Commandos and the further mentoring of ANA Special Operations Forces. The same concerns about the quality of the individual soldiers apply here.

“We get guys that show up on day one who say ‘I don’t want to be here,’ and we get guys who go AWOL. The other day we had a guy who had tunneled under the wall of the commando compound and was bookin’ it toward the gate.,” said Canadian Special Forces Operator, MCpl Green.

At Kabul Afghan International Airport a small group of Canadians is working with the Afghan Air Force (AAF) to develop and nurture the same system of planned learning in the creation of pilots and ground crew for any future AAF.

“In the past the Afghan Air Force had a proper university. It was pretty much dismantled by the Taliban … our new students automatically go to literacy courses, which are ninety days and we often have students repeating those, before they enter air orientation. We are at the infant stages right now,” said Canadian Air Force Major Aleem Sajan.

The risks faced by Canadians have changed since the end of the active military operation in southern Afghanistan, and the start of the teaching operation in the north, but the risks are still present. Canada’s soldiers — generally forgotten at home by a public long grown numb by the similar plodding nature of this conflict – continue to risk all in pursuit of their mission objectives.

The Taliban insurgency is a creeping, insidious enemy here in the north of the country. In Kabul – where a majority of the population are supportive or at worst ambivalent of the Afghan Government – the Taliban are forced to keep a lower operational profile. The danger of sudden death is always there though for Canadians. It could be a Vehicle Borne Improvised Explosive Device (VBIED) attached to any erratically driven Toyota by a deluded woman in the street around you (Kabul, Sept. 18, 2012). Or a suicide vest packed with shrapnel wrapped around a misguided teenage boy (Kabul, Sept. 18, 2012). Or more and more likely, it could be any ANSF member you trust standing right next to you. (Kabul, August 7, 2012).

In October, Canada will end this rotation of Operation Attention, so far we have lost only one soldier – MCpl. Byron Greff was among 17 people killed by a VBIED almost a year ago.

“There is little doubt we have been lucky,” said Colonel Ian Hope, commander of the CFC at Camp Blackhorse.

And at least 50 ISAF personnel have been killed in insider attacks since January. This week, NATO Secretary General Anders Fogh Rasmussen reportedly said he is considering withdrawing Western troops from Afghanistan, saying the Afghan security trainees who have turned on their Western allies had, in doing so, damaged the relationship between the international forces and the Afghan police and military.

“There’s no doubt insider attacks have undermined trust and confidence, absolutely,” General Rasmussen said in a recent Guardian article. “It’s safe to say that a significant part of the insider attacks are due to Taliban tactics … Probably it is part of a Taliban strategy.”

Being the only Canadian journalist out here was a little embarrassing. I feel there were many far more talented journalists with a much better world knowledge than me who should be here doing this job. I was disappointed that I could not do more, could not cover more, and could not tell more stories. More Canadian news organizations should be out here looking hard at the amazing work being done … and the possible futility of it all.

For the stories I did manage to tell I want to thank all of the Canadian and ISAF troops who did everything they could to help me. You know who you are. I could not have done any of this without you accepting me into your midst and allowing me to see for myself. I salute your openness and your belief in freedom of the press – regardless.

And a special shout out to all of the Force Protection movement team in Kabul. These are the men and women who brave the possibility of VBIEDs to move personnel around the city of Kabul. I had planned to spend some time with them and write a piece on their unique and challenging task. Unfortunately I simply ran out of days. Next time for sure. Thanks for delivering me safely every time guys. Thanks to you I am standing on my doorstep again.

Rich, out.